I can still remember the first Olympic image that made a lasting impression on my athletic life—Michael Johnson winning the 200-meter dash in his gold shoes. I wanted to learn from an athlete like that, not just watch him. What did he do that lifted him to greatness?

Trainers or amateur athletes have much to learn from the best. Their hard work and dedication can motivate us, but their sport-specific training offers more specific rewards. Looking into elite training protocols and exercise selection, we can see that most Olympic athletes have two things in common: strong quads and a powerful posterior chain. Not one or the other—both.

.jpg)

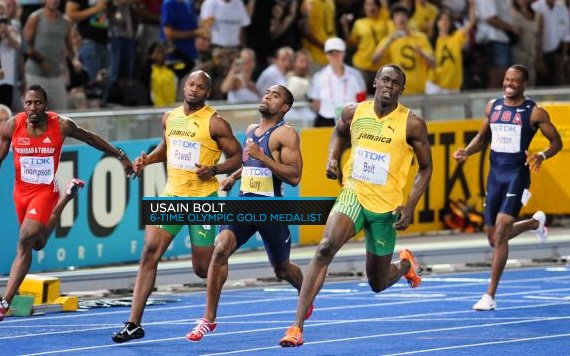

You won't find Usain Bolt sliding his stems into a tiny pair of skinny jeans after the 100-meter dash.

Olympic-caliber athletes don't have small legs, and they didn't reinvent the wheel getting big ones. Techniques like tempo changes, and movements like power cleans and medicine-ball slam box jumps aren't new or earth-shattering. But working them into your routine is the key building legs that will carry you to greatness.

Find Your Strength Ratio

When it comes to anatomy, balance is about opposing muscle groups falling within a certain strength ratio. The ideal situation isn't having quads and hamstrings that are conjoined identical twins. Hamstrings strength should be at least 60 percent, but ideally 80 percent, as strong compared as quadriceps.

It's easy to assess your hamstring-to-quadriceps strength with a comparative lift examination. If you can front squat 85 percent of your back squat, your hamstring-to-quadriceps strength is within an optimal strength ratio. (I'm referring to raw totals). The front squat doesn't have the forward torso angle of the back squat, and this lack of back extension transfers the stress to the hamstrings.

A lagging front squat means you need work on your posterior. What if you don't? Muscle imbalances lead to poor movement mechanics, and poor movement leads to injury. More specifically, imbalance between the quads and hamstrings has been cited as a leading factor in hamstring strains1. Especially when it comes to powerful movements like sprinting, overpowered quadriceps can cause a disastrous overloading of the hamstrings.

Don't Let The Quads Rule

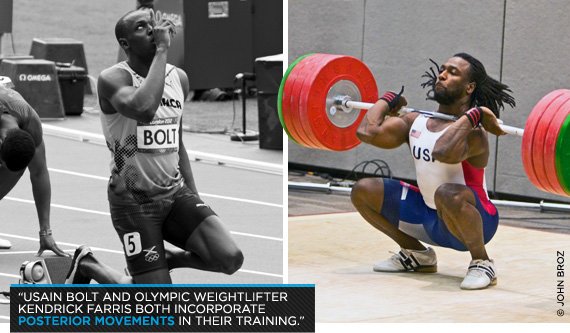

If high IQ makes world-class scientists, strong posterior chains make world-class athletes. Usain Bolt and Olympic weightlifter Kendrick Farris are just two of the many Olympians who incorporate posterior movements like good mornings, power cleans, and sled drags in their training. Ryan Lochte can even be seen dragging a boat chain during his on-land training.

Acceleration is the key to success in sports, ranging from soccer to Olympic lifting, and powerful glutes and hams are the source of acceleration. But as these athletes show, it takes more than the ability to squat massive loads to build the power necessary for something like sprinting. Pulling a mass both forward and backward blends sport-specific training and traditional weight room movement. Each is essential for speed development.

Mike Boyle calls sled marching a "special type of leg press" for athletes2. Heavier loads cause the body position to mimic starting position of a sprint, and few activities give better reinforcement on how to produce force. The extension at the hips after the pressing phase of the stride engages the glutes, driving an athlete forward powerfully.

What can you take from the training routines of the best? The posterior chain should always factor into training protocols. If you're all quads and no glutes, it's time to focus on the opposite side.

Those Quads Still Matter!

From the knee drive and push out of the blocks, to the overhead squat after the catch of a heavy snatch, quadriceps do serious work for athletes. But training superior quads, either for sport or muscular development, isn't as simple as just squatting. True quad strength hinges on appropriate exercise selection that stimulates change without overtraining.

Usain Bolt does heavy lunges and explosive barbell step-ups to strengthen his quads, while staying sport-specific. You may know or use step-ups, but chances are yours are slow and methodical. Sprinters do them explosively. Whatever your goals, tempo changes on the concentric portion of the movement can offer huge returns on muscular development as long as you maintain form.

Swimmers also have a unique approach to leg training. Ryan Lochte's need for quadriceps strength is met in a novel way, by mixing a box jump with a medicine ball slam, a move for which he can thank his strength coach Matt Delancey. The idea is simple enough: Slam the ball on top of the box, and after the ball bounces once, jump up on the box and catch it. This combines a lower-body dominant plyometric movement with power development for the upper body. It is more difficult than it looks—especially with a 40-inch box and a 40-pound medicine ball, like Lochte uses.

Ryan Lochte's Most Innovative Workout: Box Jump

Watch The Video - 01:02

The Big-Leg Workout

It's all too easy to focus only on our talents—such as a massive back squat that also serves as an easy conversation starter—and let lagging body parts continue to lag. If your program is missing some pieces, or your hamstrings are out of balance to your quads, try this Olympics-inspired routine to build a podium-worthy lower half.

Sources

- Croisier JL, Ganteaume S, Binet J, Genty M, Ferret JM (2008) Strength imbalances and prevention of hamstring injury in professional soccer players: A prospective study. Am J Sports Med 36:1469-75.

- Boyle, M (2010). Advances in Functional Training. Vol. 1. Aptos, CA: On Target Publications.