To read this article, you turned on your computer or mobile device. To follow the advice that it contains, you'll lift weights from a rack or other station. At every turn, you use your arms, that most imaginative, essential and occasionally eye-popping part of human anatomy.

All that lifting, embracing, carrying, throwing, catching, reaching, and grasping takes a toll. Fatigue is inevitable. Injury is possible. Slam the weights around the gym, and you may find your arm in a sling soon enough.

To protect yourself from harm, you must understand how your arms work. So let's begin with a little anatomy lesson.

Arm Anatomy

The upper arm consists of one bone, the humerus, and five major muscles. The biceps brachii splits in two heads, the long and short head, as it runs across the anterior of the upper arm. The triceps brachii splits into three heads (long, lateral and medial) as it runs across the posterior of the upper arm.

The biceps bend your elbows and rotate your hands. They are the prime movers in elbow flexion and wrist supination. The triceps straighten your elbows, so they are the prime movers in elbow extension.

The forearm consists of two bones, the radius and ulna, and approximately 20 muscles. In all, the human arm consists of 20 bones and about 43 muscles. Each of those 43 muscles becomes a tendon at a musculotendinous complex, and each tendon then connects to a bone. This structural schematic holds muscles in place and allows for movement.

Every muscle, bone, tendon, complex, ligament, and tissue can incur injuries that can limit your mobility and perhaps force surgery. Let's explore the injuries of the arm, how you can protect yourself, and how to rehab in case of harm.

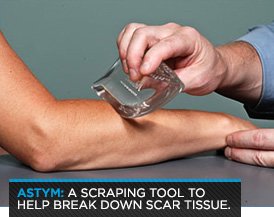

Like every other joint in your body, the arm contains tendons, which connect muscles to bones. These tendons help you move, but these same movements can injure the tendons under adverse conditions. You may know tendonitis injuries as "tennis elbow" or "jumper's knee."

"When a tennis player hits a backhand, the arm muscles are supposed to absorb the shock," says Jim Moore, exercise physiologist at the Idaho Sports Medicine Institute. "As a player smacks the ball, that impulse wave travels up the arm, through the muscles, then the lateral muscles that attach to the elbow. Those tendons and flexor muscles must then take the shock load. Tendons don't like that."

Repeated shock fatigues your muscles, which makes them rigid, so they don't absorb the shock of the collision. When elbow tendons take the abuse, this causes inflammation in the joint.

Any repeated motion can inflame elbow tendons, so tendonitis is also common among construction workers and physical laborers.

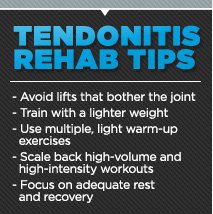

Regardless of what caused your tendonitis, you should ice your elbow immediately. Rest it, halt the activity that led to the pain, and stretch the area multiple times per day. Strengthen the muscles in your forearm to increase their endurance.

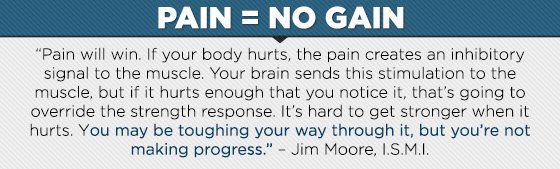

Tendonitis can sideline you from training, but it's better to rest than train through severe pain. When you're ready to train again, use a lighter weight. If you experience more pain, set the weight down. Remember to recognize the difference between pain and soreness. In the case of recurring pain, split your training to give individual muscles and joints more rest.

"Exercise promotes good healing," Moore says. "It brings blood into an area. If you only work a muscle group once per week, the tendency might be to push it too hard that one day. Instead, work that muscle group with lighter weights 2-3 times per week while rehabbing."

Strength and endurance only partially protect you from tendonitis. You still run the risk that you'll get fatigued and hurt. In addition to exercises, make other adaptations: Switch to a two-hand backhand to better absorb the shock. Get a better hammer, or switch professions. Rest! Ignoring pain will only make it worse. Inflammation spreads like wildfire. Douse it immediately, or it will burn you up.

You'd creak like the Tin Man if it weren't for your bursa sacs, which secrete a fluid that lubricates your joints. But with repeated pressure or pinching, a bursa sac can become inflamed and swollen, causing bursitis, a painful nuisance.

The condition is easier to cause than it is to fix. "You treat the bursitis by changing the factors that create it," Moore says. "If it's in the shoulder, you strengthen the rotator cuff muscles. You rest and ice it. You strengthen stabilizer muscles."

Early on, when bursitis starts to bug you, ice it and stop the movement that irritates the area. Switch to dumbbells or change exercise angles. Once the joint is swollen, it becomes easier to irritate. Eventually, the bursitis can worsen until the offending bursa sacs need removal.

The bones in your arm are connected by ligaments. When force exceeds the ability of ligaments to handle, these ligaments can tear—or be ripped from the bone (avulse).

It's not always sudden moves that lead to a tear. The biceps long head attaches to the top of the glenoid process in the shoulder socket. Consistent impingement may wear down the biceps tendon, leading to a chronic tear.

"You can pull or tear the tendon in the junction where the muscle ends and the tendon begins, but typically, it happens in the tendon, or the tendon is avulsed," Moore says. "Any kind of hard, resistant flexion will tear it. Typically it's caused by overreaching, then encountering a force, as in a hard landing."

This, in turn, often happens when you're tired but still playing a game or sport. When you get tired, your risk of injury increases, and you are always capable of fatigue.

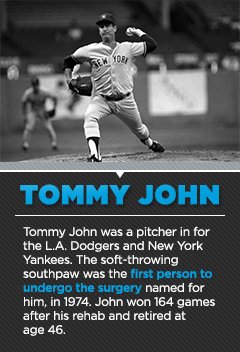

With any biceps or triceps tear, you need surgery within a couple of weeks. Otherwise everything starts to scar down. You don't drive your truck after you throw a rod; you shouldn't bench press with a torn triceps. Torn tendons require a few months in the body shop.

"You can do surgery later, but it's messier, and the outcomes aren't as good," Moore says. "It's better to do the surgery right away. They go in, pull the muscle down, drill some holes in the bone, then re-suture the tendon into the bone. Then, in the normal healing process, the body will reform the connection."

The joint must be immobilized to heal. The healing period changes depending on the severity and location of the tear. If you tear something and don't fix it, it won't function the same. A biceps tear can still allow a weaker elbow flexion, but Moore says you will lose supination abilities in the arm. Not good for anyone, but especially not good for lifters.

A biceps or triceps tear takes 6-9 months to rehabilitate after surgery. Yikes. The tendon is seldom replaced. Surgeons pull the injured tissue back down and screw it into the bone, or sew it together.

Arms break. A child falls off a trampoline and snaps her radius. A skier hits a tree and shatters the ulna and radius. A middle-aged pitcher clings to fast-pitch dreams and fractures his humerus.

Many "clean" breaks can simply be put in a cast and will heal naturally in a few months. Displaced fractures and shattered bones are more difficult to repair. These severe injuries may require surgery to "re-set" the bone or brace it with internal stainless-steel plates and screws.

"It depends on how clean the fracture is," Moore says. "If it's just a non-displaced fracture, you just put a cast on it and let the ends grow back together. If bone is shattered and you break both the ulna and the radius, it may require internal fixation. Plates and screws depend on extent of the injury. It's the trauma surgeon's call."

If you have plates and screws inserted to support the bones as they grow back together, you may set off metal detectors for the rest of your life. The steel is only removed if it leads to soreness. The removal procedure is typically simple and heals quickly.

Three months after most fractures, you can begin light exercise and lifting, starting with basic range of motion tests and stretching. Severe fractures may take longer to heal, so your return to exercise will be postponed.

Recovery covers more than just the broken bone. A broken forearm limits strength from the wrist to the shoulder. The entire arm must be rehabilitated. Once you are able to move, you can progress to light exercises, heavier lifts, and sports drills.

If one of your joints dislocates, call 911, or go see a doctor immediately. Do not try to put it back in yourself. This includes fingers, wrists, elbows and shoulders. You are not Riggs in Lethal Weapon; no actor or random dude off the street has ever properly re-set a dislocation.

All joints can dislocate. They pop out in all directions, depending on the source of the force. Any sudden force can do the job. Once a joint is dislocated and re-set, it may slip out again more easily. The shoulder slips back in place if done right. If done wrong, you can do even more damage.

"Let trained professionals deal with it," Moore says. "It needs to be pulled down and guided back in with traction. The elbow is tough. It's kind of a bony socket where the ulna fits into the humerus. You can dislocate that and it's a pretty traumatic injury. It's going to create a lot of additional problems, including nerve damage. It's going to take a lot more force to dislocate an elbow."

Fingers incur damage easily. Moore says they can pop out and people panic and put it back in themselves, causing damage to very small ligaments and muscles. The wrist is similar. It contains many small bones, so a dislocation can be a complex fix.

"There's a really good chance you may need surgery after a dislocation, but that depends on the individual, how bad it is, the angle in which it was dislocated, and what caused it to go out," Moore says.

Be Fore-Armed

Strength is never contained to a single muscle. Muscle groups and systems collaborate to help you move. By strengthening the entire group, you increase your strength output. If any part of it lags, you lose power potential.

"It's all part of the kinetic chain," Moore says. "Any time you pick up a bar, if your hand and forearm muscle are weak, you fatigue more quickly."

Grip fails on heavy deadlifts, which makes many people reach for wrist straps. Moore says people reach for such assistance too soon. Exercise without assistance builds grip and forearm strength.

"People with weak hands will go immediately to wrist straps," Moore says. "Do most of your sets without those aids. Try to develop that strength. Use straps only at the heaviest weights."

To help build forearm and grip strength, try seated rows with a heavy towel as the handle. This forces you to hold on tight with your hands, building grip strength.

Your forearms get worked via normal exercises. Curls, rows, pulls, push-ups, and anything you use your arm to accomplish will work your forearm. You don't need to use isolation exercises for the forearm unless you are a competitive bodybuilder or you injure the area.

Moore also says that free weights better engage the kinetic chain in your arms. Consistent machine usage isolates the upper arm, breaking apart the chain.

And if you want to keep your arms intact, you don't want to break the chain.