"The greatest feeling you can get in a gym or the most satisfying feeling you can get in a gym is, 'The Pump.' Let's say you're training biceps. Blood is rushing into your muscles, and that's what we call the pump.

Your muscles get a really tight feeling like your skin is going to explode any minute. It's really tight, it's like somebody blowing air into your muscle. It just blows up and it feels different. It feels fantastic."

This was the legendary line from the movie Pumping Iron that any bodybuilder or fan can recite on the spot.

Interestingly, the pump has been established as the primary mode of training among bodybuilding in past and recent years. Unfortunately, many bodybuilders without sufficient knowledge or many exercise scientists/trainers without "in the trenches" experience, default to these high volume type workouts as being ideal for promoting muscle hypertrophy.

Presumably, this notion was accepted as being ideal from bodybuilders who were not natural. In reality, basically any type of training stimulus will have a positive effect on muscle growth when utilizing certain pharmaceuticals in the body (Creutzberg et al., 1999; Yarasheski, 1995).

This is where logic is lost and following flawed logic becomes evident. Again, there are two kinds of information: Misinformation and information.

As a scientific and logically based natural bodybuilder with "In the trenches" experience, I can attest to these high volume workouts not being the reason for promoting muscle hypertrophy. Since we do not have these exogenous pharmaceutical aids, we have to induce it naturally, which means, very hard work and heavy lifting.

As Anthony Monetti Jr. once said on the MTV true life series,

No steroids, I gotta work harder, so I won't have those drugs to rely on."

Scientifically, this makes sense, since we do not have that exogenous source of testosterone coming in, we have to produce that extra testosterone endogenously on top of what we already produce naturally. And since the body is resistant to change, we have to work really hard to stimulate that testosterone boost from our workouts, which means, lifting heavier weights. Research has clearly shown that the most effective workout for stimulating testosterone is high load and low rep training (Kraemer, 2000).

Balachandran (2006) stated the following:

Powerlifting, often seen as a "little-to-do-with-muscle-event," has been shown to indeed be a function of muscle mass, and lifting performance has been shown to be limited by the ability to accumulate muscle mass (Brechue & Abe, 2002). And once these elite lifters hit their genetic limits with regard to muscle mass, strength increases are marginal at best (Hakkinen et al., 1988).....

But the question remains: If strength is highly correlated with muscle size, what about those bodybuilders who are big yet not strong?

First and foremost, elite class bodybuilders are dipped in drugs. And drugs lie right to your face. Testosterone and GH administration have shown to increase retention of fluid (water/salt) within the muscle that would cause an enlargement of the muscle fibers with little strength change (Creutzberg et al., 1999; Yarasheski et al., 1995)....

It is now becoming increasingly clear that testosterone promotes its anabolic effects primarily through an increase in satellite cell proliferation and myonuclear number (Herbst & Bhasin, 2004; Kadi, 2000). Sadly for natural trainees the only viable option to activate satellite cell is through load mediated injury.

Contrary to typical high volume bodybuilding workouts, research has shown that high-load, low-repetition training is more effective than low-load, high-repetition training in building muscle size (Brooks et al., 1996). However, this is not to completely abolish the benefit from pump workouts.

In fact, this is the very reason for this article. However, I did just want to clarify that in order to build muscle, one must progressively get stronger over time, which warrants having heavy lifting days (Fry, 2004).

Two Kinds Of Pumps

To eliminate some confusion, there are two kinds of pumps:

- The Cosmetic Pump.

- The Productive Pump.

The cosmetic pump is the pump most of us perform backstage before hitting the stage to obviously make our muscles look fuller and bigger. The productive pump, involves stimulating the trained muscle group's predominant muscle fiber type and then stimulating the remaining fibers throughout the workout.

For example, the upper body does not require as many reps to get a good productive pump, however, the lower body tends to respond better to higher rep loads (Schwarzenegger, 1998). I tend to get a better leg pump on my lighter day leg workouts that have higher volume with shorter rest periods. For upper body, I tend to get a better pump when I have had at least a few heavy sets before tapering the load down as the workout progresses.

The pump, which is technically known as transient hypertrophy, occurs when more blood is coming into the muscle than is leaving that causes fluid retention in the interstital and intracellular spaces of the muscle (Wilmore & Costill, 2005).

Pump Workouts

The thing I like about pump workouts, as I like to call them, is that they create the opportunity for variety in training, they are therapeutic, and they prevent overtraining and injury. As I said, the key to building big muscle is lifting heavy, however, as we all know, too much heavy lifting can bring about injury or overtraining. This is the perfect time to cycle your heavy days with pump workouts.

Pump workouts typically involve rep ranges from 8-20 or more reps, short rest periods, and multiple sets for the same muscle group or opposing muscle groups. They can also include advanced training techniques such as:

- Drop sets

- Burns

- Partials

- Negatives

- Peak contractions

- Forced reps

Pump workouts are kind of a novelty in that they stimulate intriguing fatigue patterns if variety to training is practiced. For instance, in my calf workout today (7-25, 2007), I did an advanced technique pump set for my last set of seated calves with the help of a spotter.

The plan was to perform 12 reps with the initial load of 3 plates (45 lb plates), then add 2 plates and let it stretch at the bottom with this higher load for as long as I was willing to tolerate, then strip off the 2 plates and burn out with the 3 plates. Basically this plan was a modified version of Tom Platz's Extreme fascia expansion technique (Wilson, 2002).

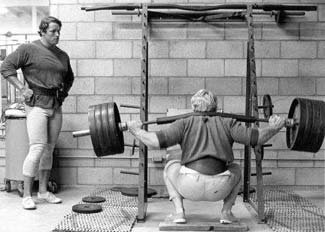

Click To Enlarge.

Click To Enlarge. Tom Platz.

I started with three plates and did 12 reps, then the spotter added 2 more plates and as he added each plate, I actually tried to hold my ankle parallel to the ground to elicit greater muscle stimulation. However, my ankle slightly lowered after each plate was added, and I held my ankle in a position just barely above being in complete stretch, then when I couldn't hold it there any longer, I let my calf muscles relax to allow the load to place tension-stress on my calves.

Once it became really painful, the spotter stripped the 2 plates off and I repped out with 3 plates. Oh by the way, this grueling set was performed after performing two sets of 10 reps with the 3 plates with a only a 10-second rest period between those two sets. These 3 sets combined into 1 set were so good, I ended my calf workout at that point.

Newfound Applications

Up to this point, I'm sure many have already known about many of the applications and benefits I have discussed so far on the pump. However, I challenge you to continue reading as you are about to enter some unchartered territory when it comes to the pump and hopefully learn some newfound applications.

Newfound Application #1:

The Pump Creates Leverage And Stabilizes Joints.

When performing tricep pressdowns, when the biceps is pumped up, it will give a rebound or cushion effect against the triceps and help you lift more weight or more reps. Basically, the range of motion is reduced, and the sticking point is pretty much eliminated.

Here is the explanation. As you workout biceps and triceps together, when the biceps engorge with blood, this fills in the antecubital space (the elbow joint space on the front side of the arm) and thus as you perform rope press-downs or close-grip bench presses, your upper arm doesn't quite touch your forearm anymore because of the blood filling up the antecubital space by expansion of the biceps.

In essence, you are creating a naturally-induced partial-rep. The engorging of blood within the muscles surrounding a joint also increases the hydrostatic pressure in the joint, thus adding more joint stability. And since the stabilization is natural and occurs internally as opposed to wearing an elbow wrap, it does not negatively effect your muscle's ability to stabilize.

This is synonymous with the criticism of wearing a belt all the time for squatting. The key is to try to allow the body to naturally support itself as long as possible, and only under extreme situations, such as a 1-RM or real heavy set, the use of a belt or wrap can become an aid.

Newfound Application #2:

The Pump Increases Strength During A Workout.

For those who have done the common ballistic stretch of fanning the arms in and out across the body to stretch the chest and shoulders will relate to this following example of how the pump increases strength. When one does this ballistic stretch when the muscles are cold, your range of motion is pretty good because tissue approximity is not an issue. However, when one gets a good pump, one can relate to muscles feeling "tighter" when stretching.

Thus, when you do this same ballistic stretch when pumped, you get this elastic rebound spring effect called a myotatic stretch reflex, which decreases your range of motion (Hamill & Knutzen, 2003). Well, this same effect is responsible for increasing one's strength by adding an elastic component to the lift (Asmussen & Bonde-Peterson, 1974; Bosco & Komi, 1979; Bosco et al. 1982; Cavagna et al., 1968) while simultaneously protecting the joint (Hamill & Knutzen, 2003).

This elastic effect is thought to occur from the muscle spindles that are more sensitive to stretch and rapid change in joint position dictated by the change in the muscle's length-tension relationship (Hamill & Knutzen, 2003).

When one has a good pump going, this effect seems to be different from the same stretch reflex commonly seen in sports such as jumping in basketball and throwing motion sports like baseball and football. However, this stretch reflex seems to be modified in weight lifting with a serious pump.

Typically it takes a jerky motion or bounce to evoke this stretch reflex, which brings stress to the joint. However, this same stretch reflex seems to occur without the typical joint stress that occurs from a bounce or momentum when the muscle is cold, due to the enhanced temperature, blood flow, and cushioning effect of the pump.

Due to the transient reduction in range of motion from tissue approximity caused by the pump, this appears to have an additive effect to naturally cushion the joints be preventing the risk of hyperextending the joint.

Anecdotally, when one is pumped, the muscle tonus is also increased. For example, when one works biceps, the angle of the elbow at rest is slightly decreased. To prove this, do the following test right now as you are reading this. Just straighten your elbow out slowly and lock the elbow to stretch the biceps. For most of you, there is minimal to no stretch.

|

What Is Muscle Tonus? Musle Tonus is the state of activity or tension of a muscle beyond that related to its physical properties, that is, its active resistance to stretch. |

|

|

||

Now, next time you get a biceps pump, do this same test, and you will most likely feel more of a stretch due to the aforementioned effects of the pump on increasing tissue approximity and decreasing range of motion through increased muscle tonus (via more sensitized muscle spindles).

Furthermore, it has been shown that the pump can increase post-activation potentiation (Moore et al., 2004). Post-activation potentiation is a relatively novel physiological mechanism in which strength and the ability to rep out are enhanced above normal (Gilbert & Lees, 2005; Robbins, 2005). In Moore et al's (2004) study post-activation potentiation was significantly increased by 51% in the occlusion group versus the non-occlusion group.

Newfound Application #3:

The Pump Is A Potent Growth Hormone Stimulator.

As far as the theory behind pump workouts and promoting growth, they are actually the most effective workouts at inducing growth hormone production (Hoffman et al., 2003; Kraemer et al., 1990). So actually, the common method that bodybuilders were using and still do use has some credence to being an effective way to promote hypertrophy in some aspects.

So in essence, in order to maximize the two anabolic hormones, testosterone and growth hormone, variation in training is imperative. For testosterone boost, high load, low rep schemes (3-5 RM) are best (Kraemer, 2000) and for growth hormone boost pump workouts (8-10RM with short rest periods) are best (Hoffman et al., 2003; Kraemer et al., 1990).

Another reason for the pump stimulating muscle growth is due to the occlusion effect it has on circulation to the worked muscles. There have actually been occlusion studies looking at these effects. These studies have shown that the anabolic effects are enhanced when partial-occlusion occurs (Moore et al., 2004; Takarada et al., 2000a; Takarada et al., 2000b).

In other words, the weight lifted does not have to be as heavy to stimulate a growth hormone response when occlusion occurs. This same effect is thought to occur during a pump workout, in which natural occlusion of the venous system occurs, thereby stimulating a similar hormonal outcome.

My basic understanding behind the stimulation of GH release is that there has to be some kind of stressor on the body. This is where when one is working a muscle during a fatiguing set, the weight becomes less important, while squeezing and pushing the muscle above its capacity to perform becomes more important.

This stress-induced effect of the pump on the muscle occurs by way of cellular hydration that is mediated through metabolic by-product saturation. Research has shown that cellular swelling and hydration induces positive anabolic effects by inhibiting protein breakdown while concurrently promoting protein accretion (Haussinger, 1993; Waldegger, 1997). This feeling of the muscles feeling saturated and blown up is what stimulates growth hormone.

However, let me make it clear that heavy lifting is a prerequisite to having the right and privilege to be able to enjoy pump workouts. Lift heavy and gradually over time increase your strength to "earn" the right to be able to have effective GH stimulating pump workouts that add to the variety in your training and prevent overtraining.

References:

- Asmussen & Bonde-Peterson. (1974). Storage of elastic energy in skeletal muscles in man, Acta Physiologica Scandinavica , 91(3), 385-392.

- Balachandran, A. (2006). Hypertrophy and Load: Part III. Retrieved August, 5, 2007, from www.mindandmuscle.net

- Bosco & Komi. (1979). Potentiation of the mechanical behavior of the human skeletal muscle through prestretching, Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 106(4), 467-472.

- Bosco et al. (1982). Neuromuscular function and mechanical efficiency of human leg extensor muscles during jumping exercises, Acta Physiologica Scandinavia, 114(4), 543-550.

- Brechue & Abe (2002). The role of FFM accumulation and skeletal muscle architecture in powerlifting performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 86(4), 327-336.

- Brooks et al. (1996). Exercise Physiology: Human Bioenergetics and Its Applications. Mayfield Publishing Company, Mountain View, CA.

- Butler, G. (Producer/Director). (2003). Pumping Iron: The 25th Anniversary Special Edition [Motion picture]. (Available from Home Box Office, Inc., 1100 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10036).

- Cavagna et al. (1968). Positive Work Done By Previously Stretched Muscle, Journal of Applied Physiology, 24(1), 21-32.

- Creutzberg et al. (1999). Anabolic Steroids. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care, 2(3), 243-253.

- Fry, A.C.(2004). The role of resistance exercise intensity on muscle fiber adaptations, Sports Medicine, 34(10), 663-679.

- Gilbert & Lees (2005). Changes in force development characteristics of muscle following repeated maximum force and power exercise, Ergonomics, 48(11-14), 1576-1584.

- Hakkinen et al. (1988). Neuromuscular and hormonal adaptations in athletes to strength training in two years, Journal of Applied Physiology, 65(6), 2406-2412.

- Hamill & Knutzen (2003). Biomechanical Basis of Human Movement, 2nd Edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, MD.

- Haussinger, D. (1993). Cellular hydration state: An important determinant of protein catabolism in health and disease, Lancet, 341(8856),1330-1332.

- Herbst & Bhasin (2004). Testosterone action on skeletal muscle, Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care, 7(3), 271-277.

- Hoffman et al. (2003). Effect of muscle oxygenation during resistance exercise on anabolic hormone response, Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 35(11), 1929-1934.

- Kadi F. (2000). Adaptation of human skeletal muscle to training and anabolic steroids, Acta Physiologica Scandinavica Supplementum, 646:1-52

- Kraemer et al., (1990). Hormonal and growth factor responses to heavy resistance exercise, Journal of Applied Physiology, 69(4), 1442-1450.

- Kraemer, W.J. (2000). Endocrine responses to resistance exercise. In T.R. Baechle, R.W. Earle (Eds.). Essentials of Strength and Conditioning (2nd edition). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Lope, P. (Producer/Director/Editor). (2003). I want the perfect body [Music Television Video series episode]. In Lope, P. (Producer/Director/Editor), True Life. Lupo Productions, Inc.

- Moore et al. (2004). Neuromuscular adaptations in human muscle following low intensity resistance training with vascular occlusion, European Journal of Applied Physiology, 92, 399-406.

- Robbins, D.W. (2005). Postactivation potentiation and it's practical applicability: A brief review, The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 19(2), 453-458.

- Schwarzenegger, A. (1998). The New Encyclopedia of Modern Bodybuilding. Simon & Schuster, New York, NY.

- Takarada et al. (2000a). Rapid increase in plasma growth hormone after low-intensity resistance exercise with vascular occlusion, Journal Applied Physiology, 88(1), 61-65.

- Takarada et al. (2000b). Effects of resistance exercise combined with moderate vascular occlusion on muscular function in humans, Journal Applied Physiology, 88(6), 2097-2106.

- Waldegger, S. (1997). Effect of cellular hydration on protein metabolism, Mineral & Electrolyte Metabolism, 23(3-6), 201-205.

- Wilmore & Costill (2005). Physiology of Sport and Exercise. 3rd Edition, Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL.

- Wilson, J. (2002). Thye Ultimate Anatomical Guide to Freaky Big Calves Part IV. Retrieved July, 25, 2007, from www.abcbodybuilding.com

- Yarasheski et al. (1995). Effect of growth hormone and resistance exercise on muscle growth and strength in older men. American Journal of Physiology, 268(2), E268-E276.

The information provided in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and does not serve as a replacement to care provided by your own personal health care team or physician. The author does not render or provide medical advice, and no individual should make any medical decisions or change their health behavior based on information provided here. Reliance on any information provided by the author is solely at your own risk. The author accepts no responsibility for materials contained in the article and will not be liable for any direct, indirect, consequential, special, exemplary, or other damages arising from the use of information contained in this or other publications.

Copyright © Ivan Blazquez, 2007. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the prior written permission of the copyright holder and author of this publication.