In a perfect world, we would all lift with perfect form, rep after rep, set after set. In the real world, we all find little ways to get the weight from point A to point B—a little momentum here, a little body English there.

These are just our conscious adjustments. What about the adjustments that we make unconsciously? The unconscious modifications we make are called compensation patterns. As opposed to cheats, compensation patterns come into play when one muscle, joint, or area of your body isn't able to do its fair share of moving a heavy object. These patterns can be subtle, but the more you increase your poundage or lifting speed, the more noticeable and potentially harmful they become.

Generally speaking, movements that don't allow for compensation patterns are safer than those that do. If you spend too much time lifting in ways that trigger these patterns, the patterns themselves become the new norm. When that happens, they begin carrying over to daily activities and will eventually lead to chronic pain. This is why it is so important to learn how to spot these patterns—and how to correct them.

Compensation Pattern 1: Knee Cave

Use a mirror or a spotter to watch your knees as you descend into a back squat. If your knees come together, it is an indication that two important kinds of muscles aren't working together. The tonic muscles are the first kind, which include your short hip adductors, hamstrings, and rectus femoris in the quads. Tonic muscles come into play when you do rhythmic or repetitive movements like reps. They also help you maintain an upright posture.

The other kind is the phasic group of muscles, including your glutes, abs, and deep core muscles. Phasic muscles work to initiate movements, fight gravity, and stabilize a squat. They do a lot of work and usually fatigue faster than their corresponding tonic muscles.

To attain compensation pattern-free movements, both of these muscle groups need to work together. However, when most people do squats, the phasic muscles tend to tire quickly, forcing the tonic muscles to compensate by working harder. This causes the knees to pull together.

When knee cave occurs, you have two options: to keep going with the incorrect pattern for another 10 to 15 reps, or to stop. By continuing, you will be letting this become the normal way that you perform the lift and you can wait for the injuries to come. Or you could stop, give your phasic muscles time to recover, then continue your set.

You need all these muscles to work in harmony to have the safest and strongest squat form possible. Adding exercises that will strengthen the muscles responsible for the compensatory pattern will help improve your body's urge to perform the movement incorrectly. This is the only way you will stick around long enough to become a squat beast.

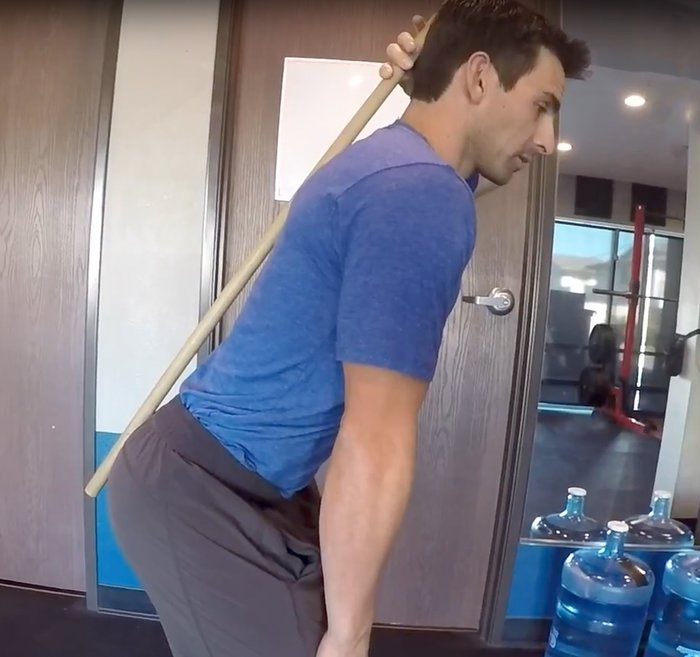

Compensation Pattern 2: Lower Back Arch

Some people believe that arching your lower back is okay during back squats—if for no other reason than it being better than rounding your back. While this is true, the arching compensation pattern will need to be addressed in the long term.

With back arching, the tonic and phasic groups are at it again! The tonic muscles involved in this pattern include the lumbar spinal erectors, hip flexors and, again, the rectus femoris. The phasic group is the same as with the knee cave.

Gravity plays a big role in this compensation pattern, but it still comes down to the phasic group muscles not having the stamina and strength to keep up with the dominant tonics. The solution is the same: stop, let your phasic muscles rest, then continue. You could also incorporate more core-strengthening exercises to target your abs and back, such as planks and crunches.

Compensation Pattern 3: Looking Upward

Excessively looking upward is an early sign that you are losing your form. Since we now know all about the tonic and phasic muscle groups, it is not hard to see why.

In this case, your phasic cervical spinal erectors are losing the battle to your tonic deep neck flexors. By letting your spinal erectors rest, you give them a chance to recharge. Since you are giving them a chance to get back into the game, you're also allowing them to grow and, eventually, work alongside the tonic muscles until the job is done.

Compensation Pattern 4: Hamstring Overactivity

I recently interviewed Equinox Tier X Coach Brenan Ghassemieh, MS, CSCS, about whether you are supposed to feel your hamstring muscles during a squat. Ghassemieh agreed that hamstrings should be involved but should not dominate.

If the hamstrings are too tight, he says, the glutes need to be strengthened. It is all about keeping the muscles working together in harmony. It can take some time, but considering the decreased risk for injury and the chance to have more productive lifts, it is worth it!

How Can You Spot Your Own Movement Patterns?

All four of these compensation patterns can be hard to spot when you're the one doing the squats. Have a friend video an entire set that includes the most challenging reps in your workout. Better yet, get a strength and conditioning coach or a movement specialist to watch your back squat. Their tips and programming suggestions might just save you from a debilitating injury with lifelong consequences.

To check for patterns, first perform a back squat without weight. If no patterns appear, continue to do non-weighted squats until you're fatigued. If you still see nothing, add weight in increments. Don't go crazy and add heavy weights just to see if you can make a compensation pattern appear. You may be one of those lucky people with no patterns at all!