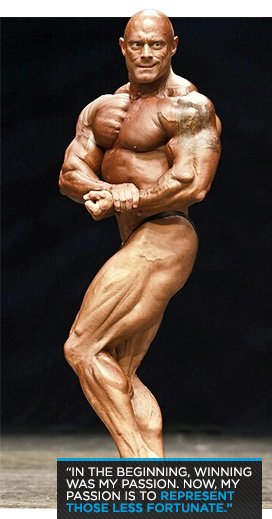

When I met Mark Antonek after he competed in the 2012 Master's Olympia, he was huge and browned with spray tan, like all the other competitors. But to my surprise, he was also warm, humble, and eager to carve out the time to tell me his story.

I'd heard a little about Antonek before I watched him compete, and I knew he had overcome significant challenges to make it to the top level of his sport. While he was onstage, Antonek's wife Darlene let me in on a few more details. The 47-year-old IFBB pro lives with advanced Parkinson's disease, in addition to severe respiratory limitations—likely due to the rescue work he performed at Ground Zero in 2001—which keep him from doing cardio.

I jumped at the chance to sit down with Antonek, confident that I was in for an interesting tale. But "interesting" doesn't even begin to encompass what this bodybuilder has achieved.

On its own, Antonek's childhood provides sufficient inspiration for a triumphant story. His father, a Polish immigrant, and his mother divorced when he was 7 years old. Afterward, Antonek's mother, an abusive alcoholic, took young Mark and his 4-year-old brother to live with her to New Jersey.

Throughout his childhood, the small, thin Antonek wanted to grow muscle in order to defend himself and his brother from their mother's violent behavior. He improvised exercises in the attic and snuck into the YMCA, but neither helped him grow. As a freshman in high school, Antonek was 4-foot-10 and weighed 88 pounds.

While under his mother's roof, Antonek ran away from home frequently. "I stayed up late and didn't go to school very often," he says. He was finally picked up by the police one night when he was 15, and the state took over. He and his brother were rescued from their mother and sent to live with their father. In this safe environment, Antonek went back to school, graduated, and went on to college. During his junior year of high school, he also began weight training, using a modest beginner's set in a friend's basement.

It didn't take long for Mark to outgrow his friend's 110-pound weight set and graduate to the local YMCA. At age 18, he took another step up, to the Diamond Gym outside of Newark, New Jersey. At this serious lifting gym, used as a home-base by a handful of national-level competitors, Antonek had his eyes opened to the possibilities of muscle growth.

"It's a Rocky gym. It's hardcore," Antonek says. In fact, Diamond calls itself "Home of the Hardcore," but when Mark started training there, he was anything but. So he did what successful beginners do: He watched and learned.

"We didn't have the Internet back then, so we had to watch the biggest guys and emulate them," he recalls. "If a big dude had a Coke, I'd have one too. If one of the biggest guys was eating fried chicken, I'd eat it too. I didn't know why, of course. I just did what they did."

Antonek also watched what these beasts did in the gym and copied their workouts. He didn't yet have competition in mind, but he nevertheless received guidance in bodybuilding from a top-level competitor, former IFBB and NPC national champ Johnnie Morant.

"After I had contact with him, I wanted to be somebody people would look up to and respect," Antonek says. He worked diligently toward these goals for another 19 years before finally taking the stage.

After high school, Mark went to Morris County Police Academy in New Jersey to become a member of the county's SWAT team. In the wake of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Antonek's team was called to New York City to perform search-and-rescue work. Much of this included pulling bodies from the wreckage, doing what needed to be done without regard for the consequences.

"I'm proud of my service," he explains, "but I wasn't told to wear a mask. Those buildings were built in the '70s. I should have known there would be asbestos and [other contaminants] in them."

Mark now suffers from severe respiratory impairment, which he attributes to his work at Ground Zero. His lungs are permanently damaged. "I can't do cardio, walk up stairs, and I take oxygen shots," he says. Most people would take this as a sign that their hardcore days were behind them, but Antonek's best training was yet to come.

Antonek says the idea of trying his physique at professional bodybuilding was suggested to him after he moved to Florida in 2002, although it took several more years to come to fruition. In Tampa, Antonek started training at Bally's Gym with trainer Don Bristow, who encouraged him to enter his first show at age 40. Never one to do anything halfway, Antonek set his eyes on winning the IFBB North American Championships. He enlisted the help of IFBB contest prep coach and promoter Tim Gardner.

"I was living with my girlfriend and saving for her engagement ring," he recalls. "She broke off the relationship and broke my heart. I went into Tim's office, cried, pulled out a pile of crumpled bills, and said 'Please coach me.'" After a top-10 finish in the 2007 IFBB championship, Antonek won the Master's Overall title in 2009—exactly 20 years after his New Jersey idol Johnnie Morant triumphed at the Nationals.

Armed with his pro card, Mark cast his net even wider, competing twice in the Europa Show of Champions, and the Tijuana International. He also focused on making sure he was growing personally as well as professionally, just like when he began bodybuilding two decades earlier.

"My internal change had to be bigger than my external change," he explains.

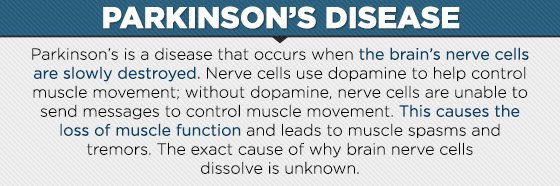

In 2010, Antonek noticed tremors in his left hand. He met therapists who told him it was just a nerve impingement. They tried all manner of treatments from physical therapy to acupuncture, but nothing seemed to work.

He was initially diagnosed with Parkinson's disease by a general practitioner based on a motor skills assessment. Antonek couldn't believe it. "I was in denial and refused to get treatment," he says. "I'm a thickheaded Polack." In 2012, he finally relented and went to the Michael J. Fox Parkinson's Research Center. There, his diagnosis was confirmed. What's worse, his disease was advanced. "It was emotional," Antonek recalls. "I broke down."

Since that day, Antonek has had a new goal in his workouts: to become more powerful than his disease. Rather than relent in the face of yet another seemingly overwhelming challenge, he says he simply asked himself, "How can I overcome this? How can I control my disease instead of letting it control me?" The answer he found was to change the reason why he was competing.

"In the beginning, winning was my passion," he says. "Now, my passion is to represent those less fortunate."

If you watch Antonek compete, his affliction is barely noticeable—just a slight shake in his left hand. "Contracted muscles don't shake as hard as relaxed muscles. So when I'm posing, I don't shake as bad," he explains.

Backstage, however, is a different story. "I shake a lot," he says. "I sometimes feel embarrassed, and that stress only increases the tremors." In a sport often defined by its intensity, he now finds himself forced to keep an even keel. "I try to stay really level. I never let my highs get too high or my lows get too low."

As Antonek describes it, Parkinson's is like having an electric wire in your arm that switches on and off without warning. "Most people can grip something and feel the fluidity of working muscles," he says. "I can't. Sometimes, the entire left side of my body shakes. I can go days without sleeping."

Despite the obvious difficulties Parkinson's disease presents, Antonek has had no choice but to open himself up to the disease, and to learn what it had to teach him. "Parkinson's has helped me leave my ego at the door," he says. "A lot of guys try to be the strongest guy in the gym. I'll never be that, so I just concentrate on growth."

To combat his shaking limb, Antonek uses wrist straps, lighter weights, and a dedicated spotter who also happens to be his wife. He has to work harder than most guys, but that doesn't discourage him. "I might have a disability, but I try not to let it dictate what I can and cannot do," he says. "Don't let negativity disrupt your life. Let it run off your back like water off a duck's ass."

When I asked if he thinks of himself as an inspirational man, Antonek is demure. "I look at myself in the mirror every day. I just see what I've seen my whole life," he replies. "But I've been told that I have a unique story, and I hope that story can help inspire others. If a 48-year-old with a disability can get on stage, then anything is possible."