Your high-school coach may have told you that your post-workout cool-down was the ticket to reduced muscle soreness, but research indicates that's not true.[1] In fact, on a scale of "not at all important" to "vital for your workout," cool-downs rank as "kinda nice to do." They play a role, and they certainly help with your immediate recovery, but if you must shave time from your workout, the cool-down is one place where you might be able to gain some time.

In addition to not helping with the dreaded delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), cooling down with active recovery and static stretching helps your future anaerobic performance or flexibility about as much as simply sitting still.[2] But that's not to say that slowing your body down gradually after a workout isn't a good idea.

When Your Workout Ends

When you exercise, your body is in an excited state: Your heart is pumping blood at a powerful clip, your lungs are working hard to keep up with oxygen demand, and your muscles are generating energy and waste byproducts. As such, your muscles are engorged with blood and other bodily fluids. When you stop exercising, your body must reverse the whole process to return to homeostasis. Your heart and lungs do the bulk of the work, which they'll do regardless of whether you slow things down gradually or suddenly. But the gradual approach is a better idea.

Think about it this way: If you're driving on an empty highway at 60 miles an hour and want to stop the car, it doesn't matter whether you slam on your brakes or gradually slow down. But slamming on your brakes at that speed isn't without risk; You could end up with a seatbelt bruise across your chest or a mild case of whiplash.

Likewise, "slamming on your brakes" after a workout could result in blood pooling in your extremities, a fast change in blood pressure, and subsequent dizziness. By keeping your body moving, your muscles continue contracting, preventing pooling of blood in the extremities and reducing the likelihood of dramatic changes in blood pressure. This can be particularly important if you have any heart problems.

Here are several rules of thumb for giving your body its much-appreciated "recovery assist."

Keep Moving

The ideal cool-down depends on whether you were doing strength training or cardio. For the latter, there are some clear signs of when you have cooled down enough.

"From a cardiovascular standpoint, a cool-down should last as long as it takes for your heart rate to return to within 20 percent of your resting heart rate, and for you to stop sweating and breathing heavily," says William P. Kelley, a doctor of physical therapy and strength coach who specializes in sports physical therapy.

It's harder to tell when you have cooled down enough after strength training, but Kelley has a suggestion:

"From a muscular standpoint, you need time to address all the muscles used during the activity you performed. A rule of thumb for cool-down time is 15 minutes, but it depends on the individual."

Either way, the goal is to keep moving. For instance, if your workout was heavily weighted toward running, gradually slowing to a jog then a walk is an excellent way to start your cool-down. And if you just spent your workout lifting legs, you might want to start with a series of lower-body dynamic stretches followed by a slow walk.

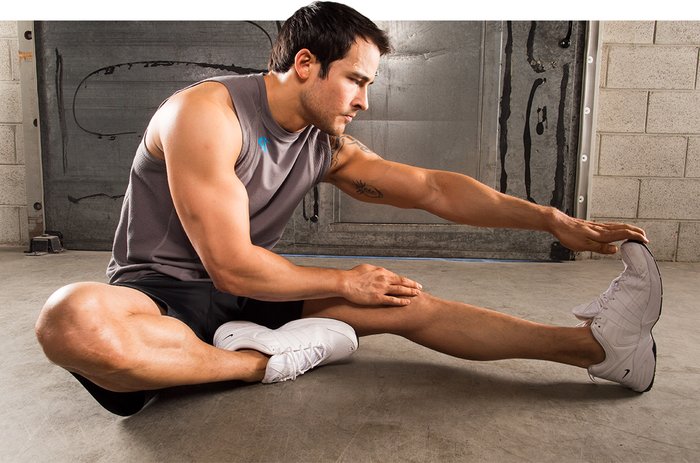

Stretch Things Out

The best time to engage in static stretching is when your body is nice and warm, just as it is following a workout. (We don't recommend static stretching as a warm-up precisely because your muscles are cold and stiff.)

Static stretches held from 10-30 seconds can help maintain and increase range of motion and flexibility. If you want to increase range and flexibility, your cool-down period is an excellent time to perform this style of stretching.[3] Kelley's only tip is to wait until your respiration and heart rate have slowed before you start these stretches.

Roll Out the Kinks

Nobody wants to pull out the foam roller after a workout, but some studies indicate that a post-workout roll could reduce DOMS in the days following a tough workout.[4,5]

"Foam rolling is a type of myofascial release that helps you feel looser and lighter," says Lauren Alix, a physical therapist and certified strength coach who works at the Hospital for Special Surgery. "Rolling helps to break up adhesions and increase blood flow to your muscles."

The trick, of course, is to do it correctly. Focus on the muscles targeted during your workout, and perform slow, controlled rolling over each muscle belly, avoiding joints and bony points. And when you find a tight knot, stop rolling and "melt" into the roller until the knot loosens up.

Rehydrate

While post-workout hydration isn't limited to your 15-minute cool-down, it's a good time to start replenishing the water your body lost through sweat and respiration. All your body's chemical processes take place in the medium of water, so if you're dehydrated at the end of your workout, your body will have a harder time recovering.

Start the rehydration process by sipping on a bottle of water as you're cooling down. How much you need to drink will vary depending on the type of exercise you performed, how hard you worked, and whether you exercised inside or outside.

A good rule of thumb is to start by drinking 8 ounces of water within 30 minutes of your workout, then continue drinking based on your thirst. You want your urine to be straw-colored to transparent yellow within a couple hours of your workout.

References

- Law, R. Y., & Herbert, R. D. (2007). Warm-up reduces delayed-onset muscle soreness but cool-down does not: a randomised controlled trial. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 53(2), 91-95.

- Rey, E., Lago-Peñas, C., Casáis, L., & Lago-Ballesteros, J. (2012). The effect of immediate post-training active and passive recovery interventions on anaerobic performance and lower limb flexibility in professional soccer players. Journal of Human Kinetics, 31, 121-129.

- Page, P. (2012). Current concepts in muscle stretching for exercise and rehabilitation. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 7(1), 109.

- MacDonald, G. Z., Button, D. C., Drinkwater, E. J., & Behm, D. G. (2014). Foam rolling as a recovery tool after an intense bout of physical activity. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 46(1), 131-142.

- Pearcey, G. E., Bradbury-Squires, D. J., Kawamoto, J. E., Drinkwater, E. J., Behm, D. G., & Button, D. C. (2015). Foam rolling for delayed-onset muscle soreness and recovery of dynamic performance measures. Journal of Athletic Training, 50(1), 5-13.