The relationship between cold exposure and increased calorie burn is not exactly news. I first heard about bodybuilders lowering their household thermostats to increase their metabolisms way back in the early 2000s. Even back then, the concept wasn't new.

It is now an accepted fact that "cold environments significantly increase metabolism during rest and exercise...Metabolic rate can increase up to fivefold at rest during extreme cold stress because shivering generates body heat to maintain a stable core temperature."[1]

When you're cold, you shiver. And when you shiver, you burn calories. But do you really have to freeze your butt off to get the benefits of artificially increasing your metabolism?

Not exactly. Researchers are now realizing that even small reductions in ambient temperature can help your body generate heat by encouraging it to form brown adipose tissue (BAT). BAT is a specific type of fat tissue that helps keep you warm by burning fat at a high rate.[2] Yes, you read that right: BAT is fat that burns fat. So the question is, how can you stimulate your body to produce more of this metabolically active tissue?

These recent revelations have led to a wave of new research studies investigating the effect of mild cold exposure on metabolism and, potentially, obesity.[3]

The Cold Exposure Trend

It seems like everyone knows someone who's using cold exposure to "hack" his or her way to a leaner physique. Methods popularized by Timothy Ferriss' book The 4-Hour Body include drinking buckets of ice water, taking ice cold showers or baths, walking around in shorts and a T-shirt on cold days, layering your body with ice packs, dropping your home's thermostat to the mid-60s, and sleeping without a blanket.

Frankly, it all sounds pretty miserable to me—plus there's not much specific research to support any one method for boosting fat loss. But positive anecdotal evidence from advocates like Ferriss and former NASA researcher Ray Cronise is certainly intriguing. If they swear by cold exposure as a way to boost metabolism and lean out, maybe it's worth another look.

Cold Vests: Is the Science There?

Continued interest in cold exposure has led to the development of cold vests. These vests are basically ice-pack holders that, unlike ice baths, chill down your body while giving you the freedom to move around and engage in other activities.

The vests are supposed to be relatively tolerable because they target parts of the body less sensitive to cold; the shoulders, chest, and upper arms. The idea is to lower your body temperate, but not so much that you shiver. But do they actually work?

I reached out to Wayne Hayes, Ph.D., a NASA scientist and the inventor of The Cold Shoulder ice vest, to see if he would allow me to put his product to the test. He was more than willing, but cautioned me not to expect miracles. He said I wouldn't see an immediate effect on my resting metabolic rate until I'd worn the vest regularly for weeks.

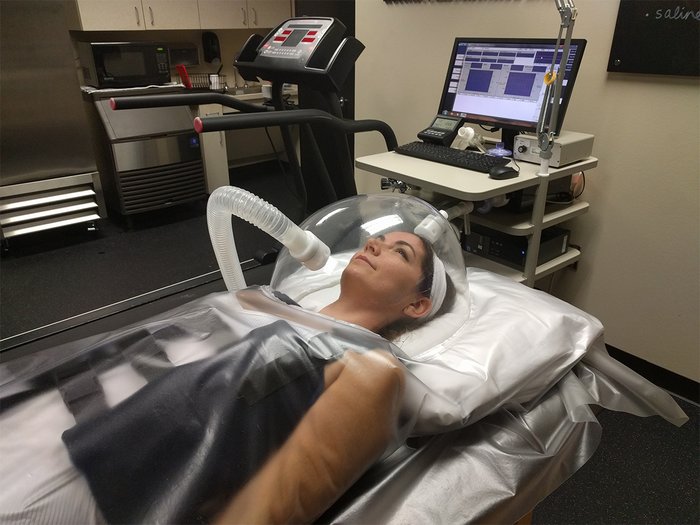

Researchers measure the effect of cold on metabolic rate with the resting energy expenditure (REE) test. It's pretty straightforward: After fasting for 12 hours and refraining from exercise for 24 hours, you simply lie in a dark room for 20 minutes with a large plastic capsule positioned above your head.

As you lie there, the air you breathe out is captured by the capsule and analyzed to determine what type of macronutrient you're burning for energy at that moment. This information—along with the total volume of air you're consuming and general information on height, weight, sex, and age—enables the researchers to estimate the number of calories your body would burn if you stayed in that position for 24 hours straight.

With one of Hayes' Cold Shoulders in hand, I called the university where I teach and scheduled an appointment to measure how the vest would affect my metabolism.

Test-Driving the Vest

Two days before the test, I slipped the vest and its ice packs out of the freezer and put it on over a sleeveless T-shirt. I cinched up the buckles to keep the ice close to my body, and went about my day with a goal of keeping the vest on until the ice packs melted.

I have to say that I'm not a fan of being cold, but even while the chill was noticeable, it didn't bother me. I made breakfast, took the dogs out, and answered emails, and I felt fine.

But after an hour ticked by and the ice packs still hadn't melted, I started getting colder—a lot colder. After two hours the ice packs were still cold, and I was starting to shiver. I put a sweatshirt on over the vest to see if that would help. Not so much. Thirty minutes later, I was done. I couldn't handle the chill any longer and took off the vest, but it took me hours to feel warm again.

In the Lab

On the day of the REE test, I arrived at the lab in the morning and performed the test first without wearing the vest. After 20 boring minutes, my REE results showed that at my current metabolic rate I would burn an estimated 1,716 calories in the next 24 hours. That sounded about right.

Next, I took the Cold Shoulder vest out of the lab's freezer and wore it for about 10 minutes to let the cold sink in before taking the test again. After another 20-minute session lying under the plastic capsule—this time with the cold vest on—the REE results showed I would burn an estimated 1,768 calories in the next 24 hours.

The results made sense: I was colder, so my body was working harder to maintain a stable core temperature. But the size of the results was disappointing. Yes, I could lose another 50 calories a day—all I had to do was keep the cold vest on all day. I couldn't stand wearing it for three hours.

My brief experiment did produce a benefit—however negligible. It also raised a lot of questions: If I had worn the vest longer before taking the test, would the results have been more significant? What if I had worn the vest regularly for a week before taking the test? What if I'd worn it for a month? And even if the REE test revealed ultimately a major gain in calories burned per day, would anyone actually want to spend that much time every day feeling cold?

For a bodybuilder or physique athlete looking for every possible edge, wearing a cold vest is probably more comfortable and cost effective than keeping your AC set to 60 degrees all the time. And wearing the vest would certainly be less painful than taking an ice bath.

The cold vest may not be a "quick fix" or a surefire solution for weight loss, but if you can afford it and are willing to commit to wearing the vest for maybe an hour twice a day—and working out regularly—you just might lose some extra weight. The key, of course, comes down to consistently exposing yourself to cold.

More Research That Leaves Questions

While traveling down the research rabbit hole for this article, I came across a particularly interesting study by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University.[4] They had five young men live in a temperature-controlled research unit for four consecutive months. During the first and third months, the researchers kept the temperature at a thermoneutral 75-degrees Fahrenheit. For the second month, they dropped the temperature to 66-degrees F. During the fourth month, they increased it to 81 degrees F. Throughout the four months, all of the subjects' meals were calorie controlled and monitored, and each month the young men went through a battery of tests.

The men were exposed to these temperatures for at least 10 hours per day. When they slept, they wore standard-issue hospital garments with a bedsheet for cover. This meant that during the second month, when the research unit was kept at 66 degrees, they weren't able to use blankets or clothing to help keep themselves warm.

After that second month, the researchers found that the men had a 42-percent increase in BAT volume and a 10-percent increase in fat metabolism. This showed that they were burning more fat after a month at 66 degrees than they did at warmer temperatures. They also experienced improved post-meal insulin sensitivity and positive changes to their metabolic hormones, including leptin and adiponectin.

These were all positive results. But the researchers also discovered that, despite increased fat metabolism, the men experienced no lasting changes in body composition after the month of cold exposure. Once the temperatures returned to normal, the men's BAT stores and fat metabolism returned to the same levels as before the cold exposure.

So the good news is that prolonged exposure to cold can increase your stores of brown adipose tissue—the fat that burns fat. Just like diet and exercise, cold exposure can help you reach weight goals. You just need to be ready to spend many days and months never really feeling warm. Some people say they'd rather just forget the cold vest, go for a brisk walk or short run, and get the same results. But, hey, if you're looking for that extra edge and have a few spare bucks, go for it!

References

- McArdle, W. D., Katch, F. I., & Katch, V. L. (2010). Exercise physiology: nutrition, energy, and human performance. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Wang, Q. A., Tao, C., Gupta, R. K., & Scherer, P. E. (2013). Tracking adipogenesis during white adipose tissue development, expansion and regeneration. Nature Medicine, 19(10), 1338–1344.

- van der Lans, A. A., Hoeks, J., Brans, B., Vijgen, G. H., Visser, M. G., Vosselman, M. J., ... & Schrauwen, P. (2013). Cold acclimation recruits human brown fat and increases nonshivering thermogenesis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 123(8), 3395-3403.

- Lee, P., Smith, S., Linderman, J., Courville, A. B., Brychta, R. J., Dieckmann, W., ... & Celi, F. S. (2014). Temperature-acclimated brown adipose tissue modulates insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetes, DB_140513.