The quest for greater muscular strength and size can be confusing, even for people who have spent years in the field. Scientific research is our best shot at providing objective and effective approaches for optimal hypertrophy, and yet the deeper you dig into research, the more you'll find experts providing conflicting opinions. Almost every day brings a new study that may or may not change everything you think you know about strength and performance—depending on how you read it.

My colleague Bret Contreras and I launched Strength and Conditioning Research to help provide personal trainers, athletes, and coaches a path through ever-growing thicket of new research. Each month, we recap and review dozens of the latest scientific studies in the fields of strength training, hypertrophy, nutrition, athletic performance, and physical therapy. Each of those is a large, diverse field of study, so we pack plenty of new and potentially game-changing information into each issue.

In this month's installment, I'll summarize three important recent studies and lay out what they mean for you. One sacred cow of the weight room will take a hit, while another can rest safe. And if you're the type who prefers to take just take one post-workout supplement rather than an entire stack, an armada of swimming rats may have made your choice a little easier.

1 / Goodbye to "Go Heavy or Go Home"

Researchers have generally agreed that loads of at least 70 percent of one-rep max are required during resistance training to instigate muscular hypertrophy under normal conditions. However, a small minority maintain that similar results can be achieved using lower loads, as long as the exercises are taken to muscular failure. Taking sets to failure is thought to produce high levels of muscle activity in the fast-twitch fibers in a similar way to using higher loads. Indeed, some researchers have reported that muscle protein synthesis can be elevated using loads as low as 30 percent of one-rep max.

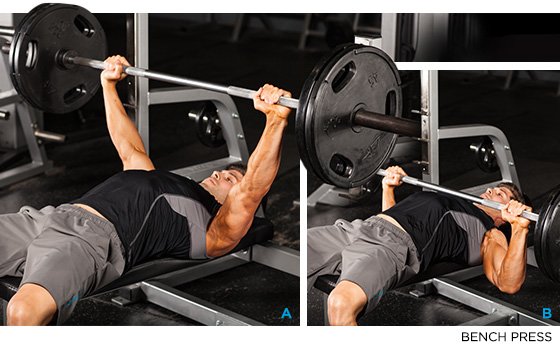

Ogasawara et al. wanted to compare the rate of muscular hypertrophy across low- and high-load resistance training routines. So they recruited nine previously untrained young men who undertook two different six-week resistance training programs, 12 months apart. The first training program was a high-load program in which the lifters used 75 percent of their one-rep max. The second training program was the low-load training program, involving just 30 percent of one-rep max.

In each program, the subjects performed a free-weight bench press exercise three days per week, on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. In the high-load program, the subjects performed 3 sets of 10 reps at 75 percent of one-rep max with 3 minutes rest between sets, and in the low-load program the subjects performed 4 sets until failure at 30 percent of one-rep max with 3 minutes rest. In each case, the subjects performed the exercise at a standard tempo with 2 seconds eccentric (lowering) and 1 second concentric (raising). After 3 weeks, the training loads were adjusted to account for the increases in strength of the subjects.

The researchers reported that strength increased significantly following both programs. However, they noted that the increases in strength were significantly lower after the low-load program than after the high-load program. The researchers also reported that muscle cross-sectional area in the pectoralis major was the same at the start of each training program, but the muscle cross-sectional area in the triceps brachii was 2.2 percent higher at the outset of the low-load program. However, the researchers noted similar increases in muscular size in general in both groups.

The researchers concluded that significant muscle hypertrophy can occur without high-load resistance training so long as sets are taken to failure with lower loads.

The study was limited in a number of important ways. Firstly, the high- and low-load programs were different in that the low-load sets were taken to failure but the high-load sets were not. Since taking sets to failure is thought to increase hypertrophy, this could have led to an overestimation of the ability of the low-load sets to produce hypertrophy in comparison with the high-load sets.

Secondly, the subjects were untrained, and this may have made it much easier for them to gain muscular size and strength. More advanced trainees might not have experienced the same gains, so we should be cautious about extrapolating the results of this study too far for now.

Finally, since the high-load program was performed first, the low-load program was essentially largely regaining previously grained muscular size, which is thought to be easier to perform due to muscle memory. This again might have led to an overestimation of the ability of the low-load sets to produce hypertrophy in comparison with the high-load sets.

All of that granted, if you are just starting out in bodybuilding, it appears that you can make use of relatively low loads for increasing strength and size so long as you take sets to failure. However, the strength gains will likely not be as significant as if you had used greater loads.

2 / Compounds for Dinner, Isolation for Dessert

Standard resistance training guidelines recommend performing large muscle group exercises such as the bench press first in a training session, followed by small muscle group exercises such as bicep curls. The rationale for this approach is that leading with the large muscle group exercises results in greater total workout volume than if those movements are performed later in the workout. However, it is not clear whether exercise order has any effect on post-workout hormone responses.

Simaõ et al. wanted to explore the hormonal responses to an upper-body resistance-exercise session and to compare the effects of performing the session in the order from small-to-large muscle groups and from large-to-small muscle groups. Therefore, they recruited 20 young males with at least two years of consistent resistance training experience.

At the outset, the researchers tested the one-rep max strength of all of the subjects in various upper-body exercises. A week later, the subjects performed two workouts on different days. The first workout was performed with compound (larger muscle group) exercises first and progressed toward assistance (smaller muscle group) exercises. The second workout was performed in the reverse order.

The researchers found that total workout volume was significantly greater when the compound exercises were performed first compared with when the isolation exercises were performed first. They also noted that growth hormone concentrations were increased significantly when the compound exercises were performed first compared with when the isolation exercises were performed first.

The researchers concluded that when larger muscle-group exercises are performed first in an upper body workout, this leads to significantly greater circulating concentrations of growth hormone.

This study was limited to upper body exercises, so it is not known whether the same results would be found when comparing lower body exercises. Moreover, it is not known whether the differences in growth hormone post-exercise would lead to any meaningful differences in either muscular hypertrophy or body composition over an extended training period. Brad Schoenfeld recently performed an extensive review of this topic and concluded that the research is currently contradictory regarding whether post-exercise hormone responses are involved in muscular hypertrophy.

However, if your goal is to maximize growth hormone release post-workout in an upper-body training session, order apparently does matter. Perform compound exercises first, followed by isolation exercises.

3 / That's the Whey

It's widely accepted that protein consumption appears to increase the rate of muscle protein synthesis. Some researchers have suggested that different protein sources such as whey, soya, casein, and wheat can produce differing rates of muscle protein synthesis, and that whey protein produces faster muscle protein synthesis than the other forms of protein. It's thought that this is because of whey's superior leucine content.

However, while there is a great deal of research discussing the impact of whey protein and leucine on muscle protein synthesis, there is much less research in respect of enzymatically hydrolyzed whey protein (WPH), particularly as compared to its component amino acids such as leucine. Kanda et al. wanted to investigate whether WPH caused a greater increase in muscle protein synthesis and mTOR signaling, which is a cellular pathway linked to muscle growth, than a mixture of amino acids.

First, the researchers obtained male rats and acclimatized them to swimming over a three-day period of pre-training. Then, one day, one group of the rats remained in their cages. They served as the sedentary control group, while the remainder of the rats swam for two hours.

Immediately after exercise, one group of the swimming rats received no supplementation, while three other groups received one of three different iso-energetic test solutions: carbohydrate (50 percent glucose plus 50 percent sucrose), a mixed meal of 18 percent amino acids, or a mixed meal containing 23 percent whey protein hydrolysate. One hour later, the swimmer rats were killed and the muscle protein synthesis rates were established.

Two hours of swimming caused a reduction in muscle protein synthesis of 42 percent in the rats which swam, as compared with the sedentary control group. The post-workout carbohydrate meal did not lead to an increase in muscle protein synthesis, but the whey protein hydrolysate and amino acid did. However, the whey meal produced significantly greater increases in muscle protein synthesis and phosphorylated mTOR levels than the amino acid meal. The researchers concluded that whey protein hydrolysate appears to be more effective in the recovery of muscle protein synthesis than either a mixture of amino acids or carbohydrates alone.

The study was limited in two key respects. Firstly, it was performed in rats and not in humans. Secondly, it related to acute changes in muscle protein synthesis, which may not necessarily translate into increased muscular hypertrophy over an extended period of time.

However, if budget or the desire for simplicity dictates that you choose between either hydrolized whey or an amino acid mix post-workout, the whey seems to be the more effective of the two in recovering muscle protein synthesis.