As fitness enthusiasts, we can easily get carried away with our primary goals. These are things like muscle gain, strength increases, fat loss, and—let's be serious—having a legit answer to questions that start with the word "howmuchya?" These are a good thing, for the most part. However, they can also lead to becoming unintentionally enamored with the "cool" exercises and elite strength benchmarks.

You know what I'm talking about: the muscle-ups, weighted dips, and conventional deadlifts with plates on plates on plates. There's something about them that just looks and sounds so badass. Close your eyes and you can see yourself ripping hundreds of pounds off the floor while everyone nearby peeks sheepishly at your strength feat. You'll gingerly kiss your biceps as you strut across the gym floor, because you'll have earned the right to do so.

But wait. Have you asked yourself if you're really ready? Think about the following: Have you mastered the basic movement patterns? Is your hip extension explosive enough? Do you have any injuries or mobility limitations which restrict the proper execution of an exercise? Do you have the baseline strength to do it properly? Does it cause you to feel what can only be described as bad pain?

If you haven't taken the above questions into consideration—and especially if you answered "no" to any of them—you're liable to find yourself over your head. Or more accurately, you might find yourself writhing on the floor as you realize a little too late that oops, that was about 200 pounds too much.

Consider this your ego check. Let's take a step back and look at how taking a different, more-personalized approach to strength training might pay off for you.

Regressions Are Your Friends!

A regression in the gym is a less-advanced variation of a major exercise such as advanced squat, pull, press, and hip-hinge movements. Often this means that you're making the movement less complex, safer, and generally more appropriate for you as an individual. It can be as simple as leaving off some weight so you can hammer out the movement with proper form, but it can also be a different exercise altogether.

How do you know if a regression is required? It's not a bad idea to hire a trainer to help you assess your level of mobility and ability. Unlike your friends, who might be as deluded about their ability level as you are about yours, an honest and knowledgeable coach can let you know straight-up when you stink, and help you locate the path out of the stench.

But just like when you're buying a car, it's great idea to have all the options in mind when you head to the lot. Let's get to know some of the undervalued relatives of the major strength movements.

This is one of the most revered exercises, and with good reason. Not only are they difficult to do properly—I'm talking from a dead hang, full range of motion, no kipping or funny stuff—but performing them with added weight brings you to a whole new level of toughness.

So what stands between you and major reps? The most common contraindication is a simple lack of strength. If you can't pull your own body weight to clear your chin over the bar, struggling and flailing isn't going to do you any good. Get strategic and focus on what you can do. As I laid out in a previous article, jump negatives (which are eccentric-only pull-ups), partner-assisted pull-ups, lat pull-downs, and inverted rows are just a few options that can help you get your chin over the bar.

Additionally, if you have a shoulder impingement, any kind of overhead motion that causes pain should probably be avoided for now. Perhaps neutral grip inverted rows, face pulls, or dumbbell rows might be a better fit until you can fix the issue.

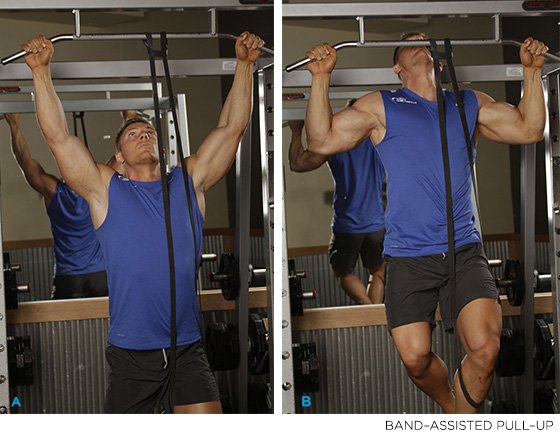

These are great because, in my opinion, they're just about the closest thing to a real pull-up. As you pull yourself up to the bar, the band offers less and less assistance, until by the time you get to the top, it's all you, baby!

But remember when performing these to control the motion on the way down as well. You should by no means look like you're falling. Think: 1 second up and at least 2 seconds down.

This is a far more advanced movement than it gets credit for. Nobody should feel obligated to try it until they're good and ready, lest they end up adding another pathetic half-squat or terrifying good-morning-squat-hybrid to the pile.

There are a number of reasons why you might not be ready to load a barbell onto your back. Poor core strength is a major one, as is a suspect lower back. Subpar hip internal rotation, limited ankle mobility, and tight shoulders can also keep you from getting where you need to be to perform the movement safely and properly.

Luckily, there are options you can pick to fit your current ability level. Aside from the various single-leg squat variations, you could try Zercher squats or goblet squats, which I explained in another article. Bodyweight squats also have far more benefits to offer than most people realize.

Front squats are great because they activate the core more than back squats and demand you keep your upper body more erect. They're also a more self-limiting exercise than back squats, meaning their precise technique makes them harder to do really, really badly. If you try to go too heavy, you end up dumping the weight on the floor, (hopefully) protecting yourself from injury.

I'm a fan of both the crossed-arm and clean grips, but whichever grip you use, remember that the bar should rest in the groove of your shoulders, not on your fingers. As you lower yourself down into the squat, really drive your elbows up. Don't let them dip down.

The deadlift is one of the most technically difficult exercises to master. Many who thought they were up to the challenge of a heavy pull from the ground have found out the hard way that they had no business even attempting it. Problems with ankle mobility, hip mobility, thoracic mobility, and core weakness are just a few reasons to steer clear of conventional deadlifts, at least for the time being.

If you're in doubt, consider sumo deadlifts, Romanian deadlifts, or rack pulls. If kinesthetic awareness is the issue—i.e. you can't properly hip hinge—I'd give a nod toward cable pull-throughs and simple hip hinge drills with no added weight.

The trap bar, also known as a "hex bar" because of its shape, is great for people with limited mobility and/or lower back problems. But don't take this to mean that the rules governing the conventional deadlift and other hip-hinging exercises don't apply here.

Be sure to keep your chest up throughout the entire movement, pull your shoulder blades back and down, and keep that upper back nice and tight.

I know it's tempting to be part of the in-crowd and spot one another over the bar every Monday, aka "International Chest Day." But the flat bench is a harsh mistress. Find me one long-time bencher who hasn't suffered from shoulder impingement or postural issues at some point!

The answer isn't to give up pressing entirely. Just select your pressing exercises carefully—i.e., not just because someone else is doing them—and balance them with plenty of pulling work. If we're talking horizontal presses, neutral-grip dumbbell bench presses and floor presses are both great options, and both are much more shoulder-friendly than a barbell on a flat bench.

I'm serious! The original strength movement may seem elementary, but before you abandon it, make sure you're doing it properly. Get on the floor at the top of the push-up position. Squeeze your glutes. Watching from the side, there should be a straight line from the top of your head to your feet. As you drop down, your elbows should be out at about a 45-degree angle from the body. Touch the chest to the ground—all the way down!—and then push yourself back up, all while maintaining that rigid body.

If you're looking for ways to make them more challenging, there are plenty. Diamond push-ups, anyone? Or how about working up to a one-armed push-up that doesn't look like a dry heave?

What's In A Name?

Just so we're clear, there's no law that says the "classic" movements have to be your goals. Plenty of people find that they prefer sumo deadlifts, trap-bar lifts, or front squats over the classic powerlifting versions, and they focus on progressing in those lifts. That's fine! The word "regression" shouldn't lead you to believe that what you're doing is in any way inferior.

On the contrary, often a regression is actually a progression for you, in that it offers you a far greater benefit than an inappropriate progression ever would. But it's also true that the big lifts earned their big reputations for a reason, so it's OK to aim for them.

How do you know when you're ready for a progression? There's no easy answer to that. For now, just practice, practice, practice. Get the form right, add some weight, then add a little more. Allow yourself to become totally captivated with whatever move you're doing, and don't leave it by the wayside until you're confident that you're legitimately rocking it.

Keep an open mind and work hard. There's no telling where you'll progress to in the long run.