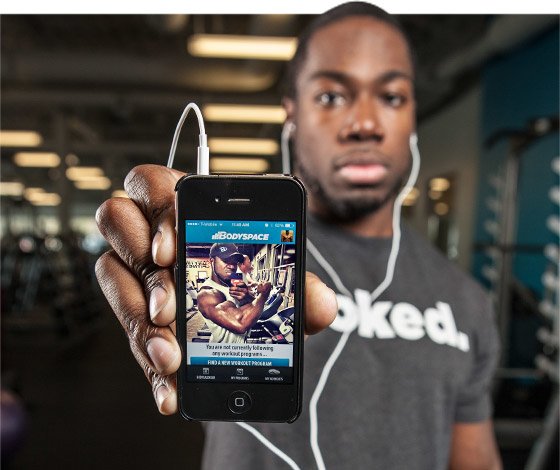

The first bodybuilding selfie on Twitter—that is, where the poster actually used the phrase "bodybuilding selfie"—was sent on February 2, 2013. Someone, somewhere had surely posted a similar image earlier on Bodyspace or elsewhere without calling it a selfie, but this is where the term launched on Twitter, says the Twitter search engine Topsy. It was from a guy named Trevor Magers (right). "Shameless bodybuilding selfie bc I hit 210lbs on the scale and still lean!" he wrote, attached to a nearly full-body photo. Shortly later, the Canadian supplement company Fusion Bodybuilding replied to him: "Great work brother; looking bawse!"

For his efforts, Trevor received just one retweet and one "favorite." He didn't want much more; after all, as he replied to Fusion, "haha, thanks bro, just trying to get hyoooooooge." But after this inauspicious beginning, the bodybuilding selfie would never be so simple again.

As Old As the Camera

It's perfectly logical to use the intersection of a camera and a mirror to track progress and share updates with friends. Bodybuilding, after all, is a visual medium; it's one thing to say "I hit 210lbs" and another entirely to show what that means on any given body. But as the concept of a selfie filtered into the mainstream—eventually earning the "word of the year" title from Oxford Dictionaries, for what that's worth—the world had no choice but to react.

And react it did, as if selfies were some sweeping wave of narcissism that transformed ordinary citizens into showy jerks. Social media hecklers came down particularly hard on bodybuilders.

Bodybuilders, however, should know the truth about selfies, which is very different from the bad reputation they've been given. There is nothing unique or even new about taking a picture of yourself. "Selfie" is just a cheeky word for self-portrait, and we've been turning the camera on ourselves since the thing was invented. One of the oldest surviving examples was taken in December of 1920, and features five mustachioed gents on a roof. If you want to go back further, one of my colleagues at Fast Company has pointed out that the very first portrait daguerreotypes ever taken, dating back to 1839, was technically a selfie.

Millions—perhaps billions—of similar photos have followed, and for the same reason we spent centuries painting self-portraits and writing memoirs: We want to remember, or to share, or to take pride in our work and ourselves. Is there a degree of narcissism in that? Sure. But that's just part of being human.

Selfies are People, Too

I became a defender of the selfie after launching a site that looked at a different breed of selfie: ones taken at funerals. I'd noticed a ton of them on Twitter and Instagram and wondered why so many kids were doing this. It wasn't a conscious movement; these kids didn't know each other. So I gathered a bunch of their photos into a Tumblr called Selfies at Funerals, and the worldwide reaction was swift and angry.

"Good Morning America" debated whether the kids in these photos were horrible people. "The Huffington Post" called it a sign of the apocalypse. Most everyone seemed to believe that these selfie-takers were self-centered brats who didn't understand death, and who wanted to make these funerals all about themselves.

Was that true? I hadn't thought much about it. So I went back to look at the original tweets and Instagram photos, and I noticed that the comments were all supportive and understanding. A kid would post a sad-looking selfie at an aunt's funeral, and their friends would reply with condolences—which is to say, the friends understood the purpose of the selfie. It wasn't to be narcissistic. It was to communicate something, a story told in a visual language and intended for an audience fluent in that language.

But of course, those selfies also reached an audience of people who didn't understand. That's the great paradox of social media: Even though our networks are made up of friends, our posts are entirely public. It's so easy to lose context.

No Selfies, No Bodybuilding

What is true about funeral selfies is also the case for bodybuilding selfies. When Trevor Magers posted his photo, it reached Fusion Bodybuilding, an organization which knew exactly why he was posting it. Both of them spoke a visual language that outsiders simply didn't. Although the exchange happened using relatively new technology, it was hardly something new.

How long have bodybuilders taken photos of themselves, or had others take pictures of them that are more or less indistinguishable from today's selfies? As long as bodybuilding has been around. Going back to the 19th century again, far more people saw Eugene Sandow's near-naked form in postcards and photos than they did in person. And how long have bodybuilders shown photos of themselves to their peers and family members for support and encouragement? Just as long. The selfie had nothing to do with it.

For what it's worth, it's not clear that Magers's 2013 photo even was a selfie. A selfie requires that the person in the photo is also taking the photo, but Magers isn't holding a camera. Maybe he just called it a selfie. Maybe he set a camera down on a timer and posed in front of it, achieving selfie status on a technicality. Does it matter? Not really. He may have been the first to use a certain phrase on a certain social media site, but he was hardly the first to stand in front of a camera—one he controlled, or one he didn't—and capture the hard work he's put into his body.

Who cares what it's called? We'll all eventually stop using the word selfie anyway. We'll forget it entirely. But the photos will, and should, continue.