His opponent called him weird. This was in interviews and pressers leading up to the fight. That particular language was reprinted often and everywhere about the young Sage Northcutt, body like a superhero doll, manufactured-looking, his smile as white and wide as a strip of coconut meat.

"It's rare that I find someone who I don't like…" said his opponent, Zak Ottow, the older and more experienced cage fighter, a grizzled Midwesterner and former bartender. "[But Northcutt] seems weird to me. His interviews are weird. I won't mind punching him in the face, at all."

A few days later, the opposite happened. Northcutt beat the tar out of Ottow with hammer fists to the head, eventually hovering like a dark cloud above the splayed-out Ottow. The older opponent held to Northcutt's left ankle like a man clinging to the outside edge of a boat, the stormy waters of unconsciousness tossing him from side to side as Northcutt leaned over and thrashed him repeatedly.

The fight was called. Ottow was out cold, dreaming of being younger, perhaps, or more handsome, an up-and-comer again, what many people dream of. Or perhaps he dreamed of nothing, lost in the deep black without thought, drifting away. I was octagon-side and felt microscopic hairs on the back of my neck wincing to find an exit.

Shades of death were in front of me, Ottow's eyes doggy paddling toward the back of his head, the crowd in my periphery at a roar.

Cartoon Lightning

But before all of that, I might have also thought Northcutt was weird, meaning atypical from my vantage—as a physical specimen, an Aberzombie, a child of God put on this earth to look better in a T-shirt than most of us mortals, to fight better, to make more money at a younger age, to eat all of the meat and drive all of the cars.

In the ornate lobby of the Grove Hotel in Boise, Idaho, I wore jeans and a white dress shirt buttoned at the collar in a nerdy street preacher affect and stood near the elevators waiting to interview Northcutt about his upcoming UFC fight, and about his life as a perceived mannequin. I also wanted to ask him, more than anything, about what goes on beneath his apparently fiberglass, perfectly smoothed shell. I wanted to know, somewhat arrogantly, I suppose, who Northcutt really is, as if I didn't already know, as if I had a right to question what was so obviously on display without the smoke and mirrors of the usual low-budget showroom. When considering a $400,000 Ferrari, do you really have to ask the floor salesman, "What's under the hood?"

The bronzed and polished elevator doors separated. Northcutt, wearing board shorts, a tight-fitting tank top, and gumball-blue athletic shoes, bounded through the opening.

We sat for an hour in a discreet booth of the lobby-side restaurant. I set my digital recorder between us and drank an iced tea. A glass of water was placed before Northcutt but he drank none of it, a few days before weigh-ins and still with 10 pounds to lose. I don't want to say his eyes were like cartoon lightning, but they were. I think they were blue, but my more certain memory is that they flashed every few seconds.

The New Breed of the UFC

I had so many deep and personal questions to ask Northcutt. I wanted to know about the troubles associated with being a prodigy—he owned more than 70 world titles in a variety of martial arts disciplines before he was out of his teens. I wanted to know about the suffering that drives ambition, the pain that forges success, the blah, blah, blah.

None of his previous interviews had covered anything of depth, I'd thought. Nobody had asked the right questions—either that, or Northcutt was practiced at holding back. In contrast, when I'd spoken with UFC legend Jens Pulver last winter, I was lucky to get in a word. Pulver is well-known for chitchat, the story writing itself the more you loosen his reins.

I won't say Northcutt swatted away my questions, but my ambitions as a reporter and the reality of my subject were overwhelmingly at odds. Northcutt seemed as nice a fellow as you'd ever want to meet, and possibly just as young and, therefore, without the time in his life for true perspective. Don't get me wrong—this isn't that article where Sage Northcutt gets called "weird" again. This is that article where it's me who's your weirdo, and Northcutt might be the new normal in our game.

The UFC is evolving. The upcoming champions are all young and laser-focused, but the old guys are the ones still asking the questions, and maybe getting them wrong. Northcutt won't comment much on his past, on the kind of thing I like to probe for, because he's living in it right now. It'll be a decade before perspective kicks in.

And about Jens Pulver, the two-time world champion, the legend, the man the UFC built the lightweight class specifically around, an OG fighter, the kind of guy I've cared for all of my life: "I've heard the name before," Northcutt tells me, meaning he hasn't watched Pulver's fights or looked very much into him at all—and why should he?

Northcutt is the new breed, a young rider on the verge of taking over the octagon for good. So what if he's one chromosome away from appearing to be a clone. Everybody after him will have to be the same, or they'll never survive.

Bright Lights, Little City

It doesn't matter that we're in Boise, Idaho, that the arena only seats 6,000 people. Any arena that sells out—and this one did—is a good arena to fight in. It also doesn't matter that on media day, 36 hours before the fight, only a handful of reporters are covering the event. There's a cardboard promotional cutout, a professional lighting kit, a few mic stands, a couple of cameras on tripods. All of this will look bigger and brighter on the internet later.

I'm sitting at a banquet table, picking at a crumbling pastry and waiting for Northcutt to come in, say his hellos, stand in front of the lights and answer the questions that he's good at by now, the "media" questions:

"What do you think about your opponent?" somebody will ask him.

"I think I'm too strong for him. I think I'm too fast for him. I'm too explosive," Northcutt will respond.

I'll be thinking about our interview in the restaurant two days before, one of the moments that'd stood out as layered, richer in some way, after I'd learned how to talk to Northcutt as a friend, instead of as a subject.

At first, I'd said to Northcutt, "I want to ask you the questions that a Rolling Stone interviewer would ask if you were Sean Penn on the beach and the photos were black and white and you were smoking your cigarettes and talking about your childhood. Do you know what I mean when I say that?"

"Not too much, no." Northcutt had responded. And then he'd laughed, but not at himself. He'd been laughing at me, maybe, or at a life that'd found him sitting in a hotel lobby with "some guy," at how fun the world can be, people just saying stuff to you and everybody trying to figure everybody out.

Later, after we'd both loosened up, we'd conversed about UFC "bad boys," the Diaz brothers, what Northcutt thinks of the rumors that he's alien-esque in his energy levels, and about Jesus Christ.

He'd said things like, "Hey, the Diaz brothers are actually pretty nice! They're pretty nice! They're cool!"

And, "Thank you. I appreciate that," skirting the connotation that he's extraterrestrial and focusing on the complimentary implications of being, in general, energized beyond the norm.

And, "Knowing what God has in store for me—it gives me hope. I kind of feel like God's warrior, pretty much. God's weapon. I'm fighting for the UFC but it's kind of my platform at the moment."

The flashes in his eyes had turned fully incandescent after I asked him a follow-up, and he'd told me: "A lot of people have a lot of things going on in their life. You'll be walking past ten people in the middle of the day and not even notice, but someone might have a family member that died, or someone might be going through a hard time. Sometimes you're the only person that someone might see that lifts them up. Someone might walk along and never have anybody smile at them, ever. Like, 'Man, no one's ever nice to me.' But then they have that one person that walks by like, 'Hey, how's it going?' And it might change their whole day, it might change their week, might change their life. The more fights I have in the UFC, the more people I meet, the more opportunities I have to make an impact."

Wait a minute, I'd thought. Northcutt might not be Sean Penn, cored-out by darkness, emotive and Dionysian, brilliantly broken in a black and white sequence of torrid affairs, but at the end of the day, a decade, Northcutt's life, it certainly won't have mattered.

When I told him, "People are saying you're the Tim Tebow of the UFC," Northcutt had responded: "Oh, that's cool! Tim Tebow's nice!"

When he finally walks into the room for media day interviews, Northcutt looks energized and almost floating, as if walking on water or air, or on the glint of stage lighting that spreads like a parting body of water from the doors of the banquet room to the cardboard cutout that says "UFC."

Inheritor of Kingdoms

On fight night, I'm octagon-side and the sound is deafening as Zak Ottow and his entourage walk out to Ted Nugent's 1975 anthem "Stranglehold." Here I come again now baby/Like a dog in heat/Tell it's me by the clamor now baby/I like to tap the streets/Got you in a stranglehold baby…

Ottow is apparently about old-school rock 'n' roll. In my head, the emphasis is on old school, and then the emphasis is on old. And yet, I'm not picking on the man. Ottow is a killer in his own right, yet he is simply a part of the world at large, whereas Northcutt is a part of a moment, a firestorm, a spark that starts in the foothills, then takes over the whole mountain range.

Northcutt's walk-out song is Lecrae's "Represent." Represent! Get Krunk! Represent! Get Krunk! If you know you're repping Jesus go ahead and throw it up!

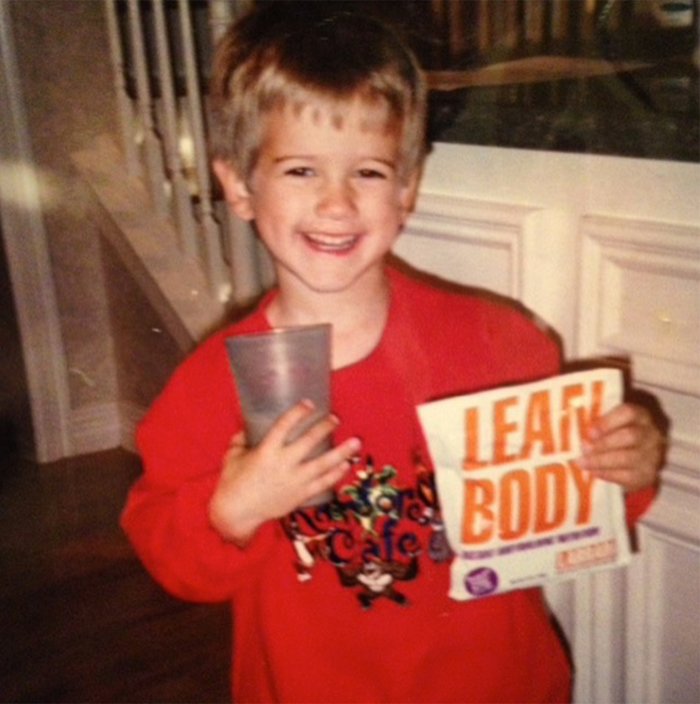

Once inside the octagon, he looks like he's stepped off a gladiator chariot, strengthened by heavy weightlifting—a rarity in fight camps—and almost 20 years of Labrada supplements, sucking down their Lean Body shakes since he was 4 years old, he'd said, a budding Ferrari guzzling its oil. Beneath the massive arena lights, things are illuminated: Ottow looks like an honest man, Northcutt looks like the inheritor of kingdoms.

Back in the restaurant, I'd asked Northcutt if he felt different from other people, if he felt like an outsider when he walked into a room, if he felt driven by something that he couldn't put words to, if a good portion of his life he'd been chasing down a feeling. His eyes had flashed with lightning bolts that were like laughter, as if he'd understood I'd only been asking that of myself, in the end.

"No," he'd smiled. "I feel like I have goals that I set, and I try to accomplish those goals, so no matter what room I step into, I know the direction that I'm wanting to head."

I'd wondered, then, if Northcutt knew who he was, inside, underneath all of the drive. Later, after his win, with his left arm raised and the sweat like a glossy clearcoat and the crowd at a drunken riot, I realized it didn't even matter. Those are only the questions that keep people like me, a generation removed from the newer model, awake into the night. Northcutt, I can guess, isn't losing any sleep.