Standing at the entrance of your gym before your 6 a.m. workout, you scan the interior, taking inventory of equipment that's available. Looking to the left, you see a man in the squat rack pushing way more weight than his form can tolerate. To the right, a woman is laboring on the treadmill, leaning so far forward that she's working her upper body a lot more than her legs. How can people like them avoid injuries, lose weight, and have a lifetime of healthy exercise habits if they're exercising with such poor form?

Chronic technique flaws can be frustrating. No matter how hard you try to remember "knees out" when you squat, do they always seem to cave? Does your cardio class instructor have to constantly remind you to keep your chest up?

In this article, I'll explain how to correct chronic technique flaws by learning how to optimize your body's neuromuscular system.

The Neuromuscular System

In the word "neuromuscular," neuro refers to the neurological system, which includes the brain, nerves, and sensors. Think "computer software and wires." The muscular system is made up of muscles, tendons, ligaments, joints, and more. Think "computer hardware."

High-quality human movement requires a well-tuned neuromuscular system, as demonstrated when you perfectly perform complex movements such as squatting without knee cave, sprinting without hip drop, or using your diaphragm to breathe during high-intensity interval training.

All of these movements seem simple enough, but I can tell you from clinical experience that life-changing injuries can occur when people do any of them without proper form.

Neuromuscular-System Training

The worst thing about doing reps with poor form is that you're training your neuromuscular system to underperform. Poor-quality motion leads to bad movement habits, which, over time, leads to deeply ingrained habits, or what is known as poor "movement memory." These less-than-optimal movement patterns can undercut future physical development.

On the flipside, however, you can train your neuromuscular system to work better so that each good rep builds good movement memory. The purpose of using threshold training is to improve these movement memories. This kind of training is especially useful if you want to lift heavier loads, run at higher speeds, or exercise for longer durations.

Remember these points:

- There isn't one specific way to train the neuromuscular system.

- Exercises can't isolate one body system: The neuromuscular system works as one unit.

- Threshold training brings progress by taking "small bites" out of your "functional gap."

Functional Gap, Functional Capacity, And Threshold

Threshold training is based on the concepts of functional gap, functional capacity, and threshold, which I learned from Richard Ulm, DC. His podcast explanation of this kind of training was an "aha!" moment for me, as I hope this article is for you.

To understand injuries in lifting or any other athletic movements from a "threshold" perspective, you first need to be able to identify your functional gap.

Simply put, your functional gap appears when your neuromuscular system no longer permits your body to move properly. I have a friend who squats with a ton of knee cave after his fourth rep at 135 pounds. Before I pointed this out to him, he had no idea when it began or even that it was happening. In fact, I had to videotape him doing squats to get him to accept it.

My friend didn't notice his bad form because at that point in his workout, his body still felt fresh. As long as he was able to do all his reps and still feel good, he figured he must have been doing them with good form. In reality, after he did that fourth rep, he had entered the shaky world of functional gaps.

All the way through the first four reps, he was operating within his "functional capacity," which is defined as the body's neuromuscular capacity to perform a movement with good form. My friend's threshold was rep 4 at 135 pounds. This is the point after which his neuromuscular system started using compensation patterns to get the weight up. He is still able to do reps 5-10, but only by compensating with other muscles and movement patterns.

Unique compensation patterns are seen in every exercise or movement pattern:

- Squatting: knee cave

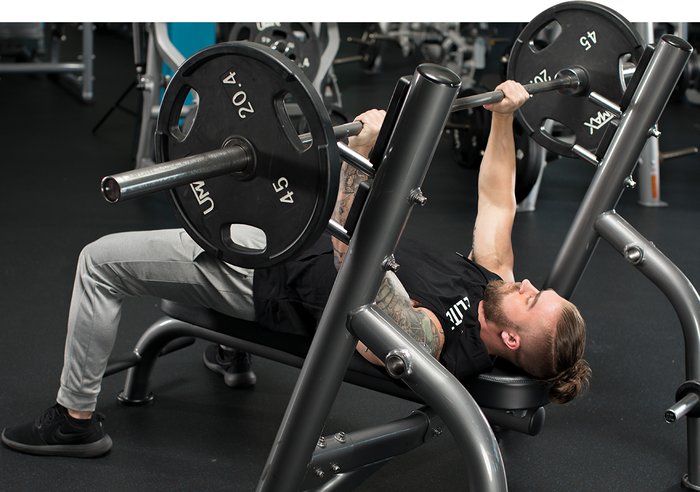

- Benching: arching the low back

- Curls: using body momentum

Making Slight Increases Over Time

The purpose of threshold training is to elevate your functional gap by taking your body to the point of neuromuscular degrade—that first bad rep—then challenging it a little more, but doing it safely.

Threshold training can be accomplished using a few variables as the challenges:

- Load (weights)

- Speed

- Duration

To challenge my friend's neuromuscular threshold using threshold training, I had him squat 5 reps at 140 pounds instead of 10 reps at 135 pounds. This was a very slight increase in load, but here was the catch: He had to perform all five squats using absolutely perfect form.

If my friend had been a track athlete instead of a lifter, I might have challenged him with speed by making him run 400 meters at a slightly quicker pace than normal. If he was into bodyweight exercises, I might have helped him work on duration by having him hold the plank position for 2 minutes and 5 seconds instead of just 2 minutes.

Threshold training is all about making slight, not dramatic, changes. It's all about making gradual increases in training that can slowly but surely raise your individual threshold.

Are there times when you might need to crush some big weights to make big gains? Sure, but not at every training session. More is not always better. The goal is to find the minimal effective increase that can safely improve your threshold.

Most of us don't make careers out of our athletic accomplishments. We work out to help us live longer and to feel and look better. If we get hurt at this less-than-full-out level of activity, it's typically the result of overly aggressive programing. Knowing your functional capacity and functional gap can keep you from trying to do too much at once.

Remember, The Tortoise Beat The Hare!

I'm not saying don't lift heavy or exercise hard, I'm saying exercise in a way that manages your risks. I've heard more than a few powerlifters say, "All great powerlifters have injuries because they train hard." In truth, you can avoid most injuries by paying attention to warning signs. As you or your training partner try to blow past the point of functional capacity, help prevent injury by spotting compensation patterns that are degrading good form.

When you do threshold training, you may not progress up the rack as fast as you might by "training hard," but wouldn't you get to where you want to be quicker if you didn't have to modify your training for six months because, say, you blew out a disc?

I take that back. Six months would be a very optimistic recovery timeline for a ruptured disc. It doesn't account for the time it will take you to recapture your pre-injury fitness level. After a major injury, you must progress very slowly to allow both your "neuro" and your "muscular" systems to recover. The two work hand in hand.

Knowing your functional capacity allows you to safely go a few—but only a few—reps into your functional gap. Instead of moving in fits and starts, threshold training helps you make the kind of slow, steady progress that lasts!