What Is Olympic Lifting | Learn the Olympic Lifts | Olympic Lift Variations | Olympic Lifter Quiana Welch | Weightlifting Champions Wes Kitts and Alyssa Ritchey

Olympic lifter Quiana "Chuckie" Welch grew up on Detroit's West Side. At first, she lived in a brick housing project that began at the potholed streets and rose to a cramped, but clean, apartment. It felt safe. Later, Welch's mother moved the family to a duplex in a rougher part of town that Welch calls "a little more 'hood."

They lived beside an abandoned house where crack addicts squatted. Welch's mother had a black Mustang that was stolen, and re-stolen, time and again. Eventually, the neighboring crack house was burned to the ground, one of thousands of vacant homes turned to cinder along the relinquished arteries of Detroit.

Sometimes, gunfire sounded. In the dark one night, Welch entered her mother's room and saw her mother asleep. Beside her head, a small-caliber bullet on the pillow glinted like a shard of glass from the broken window it'd passed through.

"It was an interesting life," Welch says, remaining diplomatic about these early childhood experiences which, however precarious, were tempered by the seeds of her athletic career. Welch spent her after-school hours in a small gymnasium consisting only of floor mats, where she learned to tumble like the WWF wrestlers she idolized.

"I had my little singlet," she says, the outfit empowering her. She remembers how strong she felt, how she understood her body for the first time, how the body's repetition became like a chant; one thing to do, over and over.

For Welch, the gymnasium offered sanctuary. It was bare bones, a box of concrete, a church where the prayer was movement.

Detroit can be hard. In back alleys, food stamps are traded for liquor. In the midst of this, with gunfire literally piercing the home, Welch's mother worked and went to school simultaneously, chasing down the only things that mattered for her daughter: The idea of a future, and the roadmap to get them there.

To Welch's mom, the mind was the way out. To Welch herself, it was the body.

Lingerie and Lifting

Welch didn't live in Detroit forever. By age 9, her mother moved them to a small town in Georgia for a good job and new life in the deep South. Welch lived in a nice home suddenly, rollerbladed with friends, pulled crawfish out of ditches, continued to practice gymnastics, and was sometimes put to work sweeping fiberglass in the back of the modular trailer factory her mother operated.

For a while, life was dreamy. She was in junior high when she took first place in the state championships in multiple gymnastics events. But soon, Welch's family outgrew the social constraints of a town that seemed increasingly unaccepting of her mother's mixed-race relationship with a white man. So, Welch's mother sent her to a boarding academy in Jacksonville, Florida, called The Bolles School, whose sporting programs were recognized by Sports Illustrated.

Welch excelled at Bolles. But, just as she'd outgrown the biases of that insular Georgia countryside, she had also now physically outgrown her dream of being a gymnast—by becoming too tall for the sport. Fittingly, she found volleyball as a replacement.

Later, while attending Florida Southern College in Lakeland, Florida, Welch attempted to capitalize athletically on her height and volleyball skills but became too mentally drained by the rigor of her schedule to follow through. She fled from the pressures of college, wandered around, even passed through New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina, then ended up playing for a season in the Lingerie Football League (since rebranded as Legends Football League), full of beautiful, physical women tackling each other in their underwear. Welch played running back and safety for the Orlando Fantasy.

"The lingerie was a gimmick," she says. "We were wearing a full face of makeup and fake lashes, but we whipped ass. There'd be skin missing off our bodies from the AstroTurf." After a pause, she adds, diplomatically again, "It was very aggressive."

When she left Orlando for New York City on a whim, nobody who knew her was surprised. Welch's life had been about movement, city to city, a life in flux.

She packed a military duffel and what she calls her "Southern Staple" Vera Bradley bag, then boarded a plane, restless for something bigger, but not yet identifiable, in her life.

She found a gym in Manhattan and worked four jobs at once, just to pay the rent. Some weeks, even affording her subway pass was a grind. The poverty was overwhelming. Still, she had begun to lift weights. "New York was hard," she says, but her body was getting harder.

Finding Black Iron

In the years that followed, Welch became restless again. She briefly abandoned New York City, did a stint in Santa Cruz, California, working at CrossFit headquarters, and even lived and worked on an organic farm in Kilauea, Hawaii. Eventually she returned to Manhattan, where she joined the CrossFit 212 team in 2014 and went to Regionals with them.

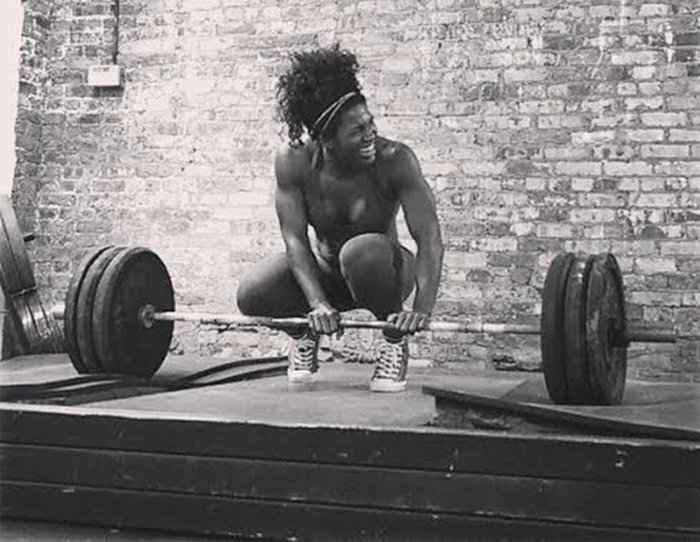

Via her CrossFit connections, in 2015 Welch fleetingly became a barbell specialist for a Boston-based GRID team. At a GRID event, Juggernaut Training Systems scouted and recruited her, convincing Welch to focus primarily on Olympic lifts, seeing the immense power she harnessed.

CrossFit and GRID were cool, but they were stepping stones to the greatness she'd find in pure Olympic lifting.

In 2016, Welch, inspired by the lessons of Juggernaut, once again left New York City to support her friend Krissy Cagney of Black Iron Gym in Nevada, where Welch now serves as head coach at the Sparks-based facility. On occasion, she commutes to Laguna Niguel, California, to meet with her Juggernaut mentor, Max Aita, for extended training camps.

Welch's childhood in Detroit, with its mats-only gym, had been her introduction to the possibilities of the body. While the years since Detroit were restless ones, Welch seems to have found sanctuary at Black Iron. The gym's slogan, "Well Wrought, Hard Fought," is befitting her journey back to what feels, finally, like a home again.

Life in the Box

Black Iron Gym is a stripped-down box gridded by power racks and littered with bumper and cast-steel plates. Grip-worn barbells scatter on the mats like pickup sticks. Galvanized braids, heavy and thick, hang from the walls like Navy anchor chains.

And inside this box, Welch has been honing her Olympic lifts. As of recently, her maximum clean and jerk is 262 pounds. Her maximum snatch is 238 pounds, the USA Weightlifting American Record for Welch's 165-pound weight class. She took that U.S. record this past December in Anaheim, California.

Black Iron is the pet project of Cagney, founder of Donuts & Deadlifts, a clothing company that bills itself as having started as a hashtag, then become a movement. The Donuts & Deadlifts motto—"EAT. LIFT. LIVE."—testifies to the changing platform of concrete box rats worldwide.

It's a platform that's more inclusive, more forgiving. And, for Cagney, Welch, and others like them, it's a multi-branded platform, with podcasts, apparel, and nutritional arms, and guerilla entrepreneurship as its life force.

Befitting the Donuts & Deadlifts motto, Welch has no problem with consuming Zebra Cakes or Chick-fil-A. The rule is that she eats what she wants, so long as it fits into her macros. The approach is a holistic one, and it appears to work. Welch's 170 pounds are overwhelmingly muscle.

"My nutrition is balanced for my sport," she tells me, "although there are some mornings when I feel rickety. I'm not 20 anymore, so I'm taking more supplements." Her essentials are BCAAs, vitamins, protein powder, and fish oil.

Her workouts are often three hours long, comprised primarily of clean deadlifts, snatch deadlifts, clean pulls, snatch pulls, jerks, block work, and CrossFit.

Detroit was a long time ago for Welch. Today, she's surrounded by tattooed bohemians with a physicality equaling our military elite's. Within coal-tinted daylight, refracted off walls painted Maglite black, life for Welch is about repetition: One set, two sets, three sets, four sets, five sets, six sets.

Life is about focus, which is the way that it's forged.

Where She's From

The sole owner of Black Iron, Cagney is a recovering alcoholic, now five years sober. At her gym, under a program called Reps for Recovery, Cagney gives out free memberships to other alcoholics trying to avoid the bottle—and those things that come after the bottle.

When I talk to Welch about this, there's a tremor in her voice when she tells me, "I've seen some of my favorite athletes relapse."

I'm in a conference room with just myself, my cell phone on the table, and a digital recorder next to it. With my phone on speaker, I can hear Welch cry.

During the few seconds of silence on my end, I think about where I'm from—Detroit, like Welch. I think about how a place gets under your skin. If it's a place like Detroit, you remember the people it tore from you, too, even if peripherally. You remember the addicts, shuffling into gutted homes.

Welch catches her breath and I ask her, "Are you sober, too?"

She tells me, “No,” adding that she doesn’t wrestle with addiction issues. “I play by the rules,” she concludes, but there’s an intonation to her voice that’s without judgment. She knows that she’s been lucky in that regard. I think about her as a little girl, cartwheeling and diving through a bare gymnasium, her singlet as shiny as red licorice while the city around her burns into ash.

And what are the rules she's referring to, I wonder, and how does she play by them?

"If you're a good person and you work hard," Welch says, "That's all there really is."

Her gym family at Black Iron is comprised of outliers, convergent only on an ideology of acceptance. They are the wanderer, or former addict, or LGBTQIA, and they also are not. The new everyman might be the everywoman. Nobody cares, and everybody is for real.

Clean deadlift, snatch deadlift, clean pull, snatch pull. To Welch, this is what matters. Over and over again, like shaping from ore. Movement on the outside, leading to stillness within. Action, maybe, as the only silence she's known.