"You've been chosen to compete in a month-long adventure race. This will be a multi-million dollar Mark Burnett production to be aired on ABC. Here's a list of things you'll need to get done before you leave for an unknown location in seven weeks. Make sure you train really hard, because this expedition is going to be incredibly difficult. Also, your involvement in this show is top secret, so you can't tell anyone anything about it."

That was basically the speech my fellow police officers Rob Robillard, Dani Henderson, and I received from a TV producer in a conference room in Los Angeles in January 2011. They flew us out and sequestered us in a hotel room for three days. We were let out only for interviews, medical exams, psych exams, drug testing, swim tests, and meals. The show was Expedition Impossible, producer Mark Burnett's epic adventure race across the kingdom of Morocco. I'd never heard of it. No one had at that point.

I was chosen because I applied to Survivor a year earlier, and I'd figured nothing had ever come of it. Then, in November 2010, I received a call out of the blue from one of Burnett's casting directors. He said, "You don't know who I am, but I know who you are." He explained the basic premise of the show and he said he wanted me to put together a team of Boston-area cops. It didn't take me too long to find two hearty souls who were up to the challenge.

After the meeting in Los Angeles, we flew back to Boston with our heads spinning, contemplating how we were going to accomplish all this while maintaining our everyday lives and working our full-time jobs.

Expedition Impossible Full Trailer

Watch the video: 02:24

Preparing For The Unknown

The show's producers told us that in our remaining seven weeks, we had to find a certified mountain climbing instructor who would sign off on forms stating that we were qualified in rappelling and climbing. Also, we needed a certified horseback riding instructor to attest that we could ride and handle a horse. We were also given a list of immunizations we needed from our doctors.

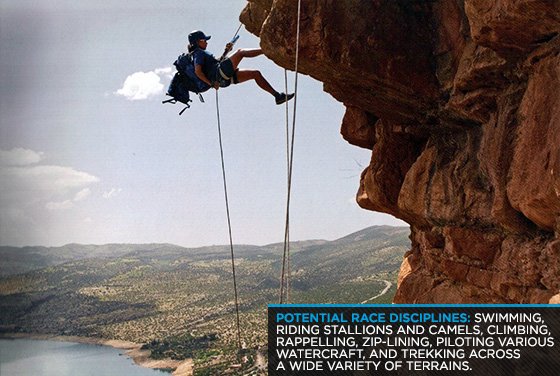

We were told "potential race disciplines" could involve swimming, riding horses "and other animals," climbing, rappelling, zip-lining, piloting various watercraft, and trekking across a wide variety of terrains. At first we were told mountain biking was involved, but at some point they must have realized that biking across rough terrain with a heavy pack was a recipe for disaster.

It was suggested that we cross-train two hours per day, and that on the weekends we should go for 5-6 hour hikes. They also reminded us to not to get hurt and to get plenty of sleep. However, how we accomplished all this and structured our training for the rigors of cross-country travel was left up to us.

Even though I am a strength-and-conditioning specialist, I believed this required a sport-specific training program beyond my knowledge. But what sport, exactly, is an "expedition?" We had no time to waste, so I decided to call in the big guns.

I contacted my friend John "Sully" Sullivan, a national level strongman competitor and the former strength-and-conditioning coordinator for Tapout Gym in Boston. I told Sully that my two teammates and I needed a physical assessment and a training program that would prepare us for the specific stresses of all these unrelated activities—and we needed it yesterday.

Obviously, Sully wanted to know what all this madness was about. I told him it was on a need-to-know basis, and he didn't need to know. What he did know is that we're cops, and I'm a member of a regional SWAT team, so he came up with a theory that we were chosen for a top-secret mission to hunt down and kill terrorists. I confirmed his suspicions and told him not to tell anyone.

The Program For The Program

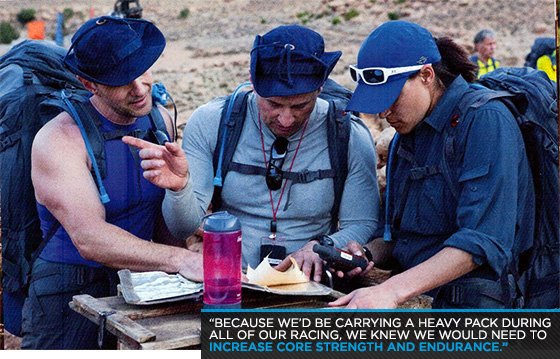

Sully did an extensive physical assessment and gave us a training program he designed to prepare us for the mission ahead. He had us stretching and strength training three days each week for about 90 minutes each session, along with various forms of cardio four times per week.

Because we'd be carrying a heavy pack during all of our racing, we knew we would need to increase core strength and endurance. We did countless sets of ab circles on a stability ball and dumbbell side bends. For endurance, we did front and side bridges, dead bugs, and bird dogs.

To prepare us for the paddling and rowing, we did inverted rows from the fixed bar of a Smith machine. We also used a high pulley with the rope attachment to do face pulls with external rotation and two-handed pulls alternating to each hip. In preparation for all the climbing and descending from mountainous terrain, Sully had us do squats, jump squats, walking lunges, and step-ups on a box. For these moves, we would either use a weighted vest or hold a pair of dumbbells.

As cops with experience in foot pursuits, we knew the biggest concern when running across uneven ground is an ankle injury. This danger is compounded exponentially by carrying a heavy pack. In order to deter this type of potentially race-ending injury, we performed a warm-up of hops in every direction, followed by a series of ankle stretches and tilts from all angles. When I wasn't trying to prepare for the show's specific demands, I also tried to fit in some of my regular bodybuilding-style workouts in an attempt to hold onto my size and strength.

This, of course, was in addition to specific activities we were practicing in preparation of the journey. These included: hiking, running, swimming, rappelling, and horseback riding.

Hiking and Running

There's an expression in the military: Train like you fight. We needed to put our boots on the ground and start logging some real miles. The problem was this was the winter of 2011 in Boston, and 10 inches of snow was falling each week.

It was time to adapt and overcome. My teammates and I somehow came up with three pairs of snowshoes, and when two or all three of us were free, we would take long hikes through the woods. If you've never done it, snowshoeing in virgin snow is like walking in knee-deep water. It was a great cardio workout, but more important, a way for us to bond as a team.

Due to the slippery road conditions, I couldn't risk going for a run, but I knew I needed more real-world cardio. So whenever I could, I put 35 pounds of weights in a backpack and went for power walks of 5-6 miles.

Swimming

We were told that we would need to pass a swim test that included a non-stop swim of 250 meters. We found a fitness center with a 25-meter indoor pool and practiced there a few times. I remembered the swimming technique I learned in junior high and I swam slowly. In this manner, I could easily complete the 250 meters.

Rappelling

I've done some rappelling with my SWAT team, so I know it's all about conquering the natural fear of heights. But we still needed a certified instructor to sign off, so I contacted the owner of Boston Rock Gym.

I couldn't tell him why we needed him to sign the forms, and our conversation went south when I told him we would be rappelling off 300-foot cliffs. I'll never forget his response. "No you're not!" he said. "No one does that. It's way too dangerous."

Just as I felt he was about to hang up on me, I said, "Would it matter if I told you we're cops and this is job-related?" I could hear the stress fade from his voice and he agreed to schedule us in. We had a private three-hour session when the gym was closed and he signed our forms.

There is nothing incredibly physically demanding about normal rappelling, but that changes when you have 300 feet of rope dangling down. The problem arises just before you go over the edge. You need to pull the rope up behind your back with your braking hand to obtain some slack. This immense amount of rope has some serious weight to it, and some of the competitors on other teams had trouble lifting it.

My team would have no trouble with any of the rappels in Morocco. This meant we would receive no rappelling airtime during the show.

Horseback Riding

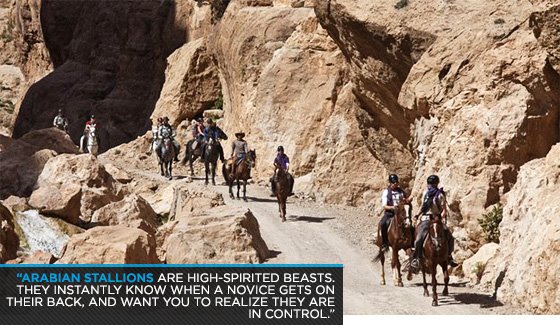

With five weeks left to go, we still needed to learn horseback riding—in Boston, in the middle of winter. Amazingly, we found a school with a covered corral and secured an instructor.

Riding a horse that's walking, I'll say in hindsight, is kid stuff. Trotting is also easy enough once your butt figures out the timing. Now let me tell you about galloping. I'm not afraid of anything, but when my horse went from trotting to galloping, it was a moment of sheer terror I will never forget.

What struck me was that I had nothing to hold onto for balance. Sure, I had the reins, but they were just hanging loose. The only parts of my body touching the horse were the insides of my knees. My head was probably nine feet off the ground, while I was on the back of a 2,000-pound running animal. My life flashed before my eyes; I've never felt so close imminent disaster.

I've seen girls using the adductor machine at the gym, but I had never remotely considered it for myself. But after my first riding session, I immediately started doing 3-4 sets each time I worked out. I figured this would help me grip onto the horse while I was riding. In hindsight I think it helped.

After three separate 90-minute sessions and we were ready for our first rodeo. Or so we thought.

Food To Go

My diet has basically been the same for years. I don't eat many carbohydrates and almost no sugar. I try to eat a lot of green vegetables, and I consume a lot of protein. I also supplement with at least three protein drinks per day. I kept this consistent throughout my show prep.

People always ask me if they gave us food during the expedition. Of course they did! The producers knew there was no way we could perform without energy. We were provided with more food than we could eat. The problem was that it was always the same food.

Each morning they'd wake us before dawn, and there would be a big basket of egg and cheese sandwiches in the middle of camp. I quickly grew to hate them, but I forced myself to choke one down because I knew I needed the calories for the day ahead.

Once we got to camp that evening, each team would have two large baskets of food. We were sure to find local bread, hardboiled eggs, bananas, oranges, apples, almonds, dried apricots and figs, olives, unlabeled short cans of sardines or tuna, and unlabeled tall cans of peas, corn or beans. We also had dry rice and pasta but I never had the energy to cook it. Sometimes we got apricot jelly, local honey, or peanut butter.

My favorite meal quickly became a banana, peanut butter, and honey sandwich. They also gave us freeze-dried meals that were prepared by pouring hot water into the packet. Some of these packets contained more than 2,000 calories, but there was so much sodium in them that they gave me a stomachache, so I avoided them. Sometimes a crew member would give out cans of warm soda and candy bars. I would never consume these things in the real world, but they were a welcome treat and much-needed calories after a long day.

Bye-Bye Boston

Almost no one knew the truth. Only my wife and kids knew where I would be for the next month. The only one at the police station who knew where we were going was my chief. He was a fan of The Amazing Race, so he was actually excited to watch us on our show. Dani and Rob made up some stories about where they were going for the rest of our co-workers, but I just disappeared.

Finally, in March, we flew from Boston to New York, from there to Casablanca, and finally to Marrakesh, Morocco. After a two-hour van ride we reached the resort that would be our home base during three days of orientation.

I should have been exhausted, but I was as excited as a kid who had just arrived at Disneyland. I tried to pay attention while we received additional crash courses in water safety, navigation, rappelling, horseback riding, and indigenous animals.

We did media interviews, we went over all the rules of the race, and we were given all the clothes and equipment we would use during the expedition.

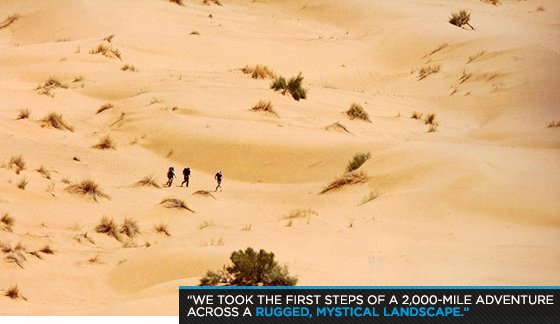

Then, just before dawn, we headed for the starting line. Six Berber warriors on horseback fired their rifles, and we took the first steps of a 2,000-mile adventure across a rugged, mystical landscape.

This Is Just TV—Right?

It didn't take long for disaster to strike. On just the second day of the expedition, I tore my meniscus climbing down a mountain in the dark. It was at the end of that day that I came to a realization. This wasn't TV danger—this was real danger.

Around the campfire, I said to my teammates, "Someone is going to die, and they're going to send all of us home and no one will ever see this show." Thankfully that didn't happen. I was able to make it through most of the race with nightly doses of anti-inflammatories from the expedition doctor and nothing more than a slight limp.

We, "The Cops," were competing against other themed teams with names like "The Gypsies," "New York Fire" and "The Football Players." We raced from one camp to the next, navigating between checkpoints and completing elaborate challenges before moving on. We conquered mountains of sand in the 100-degree heat of the Sahara Desert and climbed over the 10,000-foot summit of a snow-covered peak in the Atlas Mountains. We swam across rivers and lakes. We rode enormous, insane camels and unpredictable Arabian Stallions. We paddled kayaks, barrel rafts, whitewater rafts, rowboats and sailboats. We rappelled from cliffs more than 300 feet high and jumped from a plane for a 50-second freefall.

In addition to these intense challenges, we also ran for miles across ankle-breaking terrain wearing 40-50-pound packs. All the while, we lived and slept outside at different makeshift camps. I came looking for an adventure, and I got it.

Was I Prepared?

I trained hard, and I felt strong, but I honestly wasn't prepared for the grueling schedule of racing 8-12 hours each day, every day. My 5-6-mile power walks with a heavy pack turned out to be just a fraction of an average day in the expedition.

The swim training I did in the pool where I attempted to use perfect form was almost useless during the race. All the swimming in Morocco was done fully clothed—including shoes—while wearing a life vest and pushing our packs in front of us. I found this to be extremely tiring, and I always felt like I was swimming against the current. This was my biggest weakness, and I felt like I slowed my team down.

When it came to the horses, we had trained in Boston on Western horses. But when we got to Morocco, we were faced with Arabian stallions. These high-spirited beasts instantly know when a novice gets on their back, and they want you to realize they are in control. Some of them would buck or literally just tip over trying to throw us off. At one point, my horse stepped off a ledge, and I had to dive off to prevent the horse from rolling over me.

No Limits VS Cops

Watch the video: 02:05

Sully's training was definitely helpful, but in hindsight, I believe the best way to train would have been to actually recreate a typical day of racing. I would climb up and down a mountain for hours, and then paddle a boat for miles. You can sweat your ass off on a piece of cardio equipment in the gym, but it doesn't compare to actually racing across land and water.

This realization came to me about two weeks into the race, when I noticed a strange phenomenon. Suddenly, my team members and I no longer needed to look down to avoid stepping on every rock in front of us. We could just look forward while running. We developed an intuitive ability to avoid hazards in our path. If we had this skill going into the race, we could have been faster right from the start. As it was, we missed out on qualifying for the finals by seconds and had to settle for fifth place.

I've always trained for strength, but there was little heavy lifting involved in any of the stages. The only time strength came in handy was when we needed to carry the various watercraft down to the water. (If you think a white water raft is some rubber tube filled with air, just try lifting one up.) The extra muscle I brought into the race just turned out to be more weight that I had to carry around. After three weeks I had lost 10 pounds, and I felt like a wild animal that could run forever.

Expedition Interminable

For me, the lowest point during the entire expedition was the day we climbed a peak in the High Atlas range. My pack was heavy that day. We camped in the snow at an elevation of 10,000 feet, and I experienced altitude sickness. The injured knee was throbbing, I was nauseated, and I had zero energy and a splitting headache. All I wanted to do was lay down.

To make matters worse, my only boots and socks were soaked, so my teammates took them to the campfire to dry them out. A few hours later, they returned with two pieces of bacon that used to be my socks, along with one melted boot. I was furious at first, but then I realized this was just another challenge I needed to overcome.

I recalled an interview I'd seen with Erik Weihenmayer, who was on another team called "No Limits." Erik became totally blind by age 13. He told a reporter that if he somehow lost both legs and one arm, he would use his remaining arm to pull himself across the ground so he could finish the race. How could anyone even think about quitting when you're in the company of a guy like that?

I thought I was strong going in, but I ended up developing a new respect for the strength of the people I saw out there living and traveling the desert, hundreds of miles from a weight room. This included my fellow competitors, but even more so, the people who live their lives out in the elements, travel under their own power, and struggle just to survive. Pain is often their daily companion, and energy is a precious commodity that they have to learn to conserve.

After a lifetime in the city, with the comforts of home never too far away, I'm not ready to embrace their type of lifestyle. Just one brutal, beautiful month of it cost me plenty of comfort and a few precious pounds of hard-earned muscle. But there's no doubt that I'm stronger having gone through it.