Like just about all lifters, I became a lot bigger and stronger in my first one to two years of training in spite of the moronic stuff that I did. In hindsight, I was about as informed as a chimp with a barbell. But things worked out nonetheless. That is, at least, until I hit a big fat plateau, where things didn't budge.

Think I'm joking? Sadly, I'm not; otherwise, I wouldn't have spent about 14 months trying to go from a 225-pound bench to 230. When you're finished laughing at my past futility (or about how similar it sounds to your own plight), we'll continue.

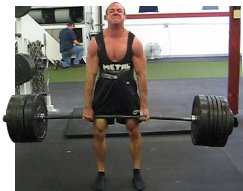

Ready? Good—because self-deprecating writing was never a strong suit of mine. I have, however, become quite good at picking heavy stuff off the floor, to the tune of a personal-best 660-pound deadlift at a body weight of 188.

My other numbers aren't too shabby, either, but this article isn't about me; it's about why you aren't necessarily getting strong as fast as you'd like. Let's look at a few mistakes many people make in their quest to get stronger. Sadly, I made most of these myself along the way, so hopefully I can save you some frustration.

Mistake #1: Only Doing What's Fun

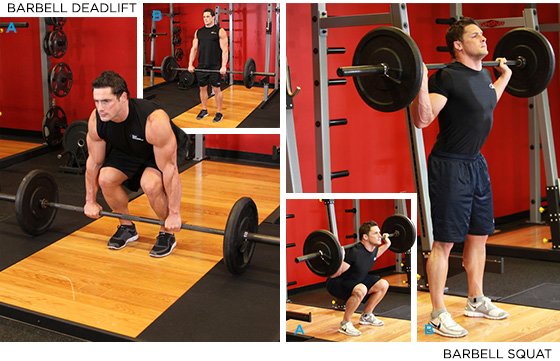

As you could probably tell, deadlifting is a strength of mine, and I enjoy it. Squatting, on the other hand, never came naturally to me. I always squatted, but I'd be lying if I didn't say that it took the back seat to pulling heavy.

Eventually, though, I smartened up and took care of the issue, by always putting squatting before deadlifting in all my lower-body training sessions (twice a week).

In addition to me dramatically improving my squat, a funny thing happened: I actually started to love to squat. Whoever said you can't teach an old dog (or deadlifter) new tricks didn't have the real scoop.

Mistake #2: Not taking deload periods

One phrase of which I've grown quite fond is "fatigue masks fitness." As a little frame of reference, my best vertical jump is 36 inches. But on most days, I won't give you anything over 34.5. The reason is very simple: Most of your training career is going to be spent in some degree of fatigue. How you manage that fatigue is what's going to dictate your adaptation over the long-term.

On one hand, you want to impose enough fatigue to create "super-compensation"—so that you'll adapt and come back at a higher level of fitness. On the other hand, you don't want to impose so much fatigue that you dig yourself a hole you can't get out of without a significant amount of time off.

Successful programs implement strategic overreaching, followed by periods of lower training stress, to allow for adaptation to occur. You can't just go in and hit personal bests in every single training session.

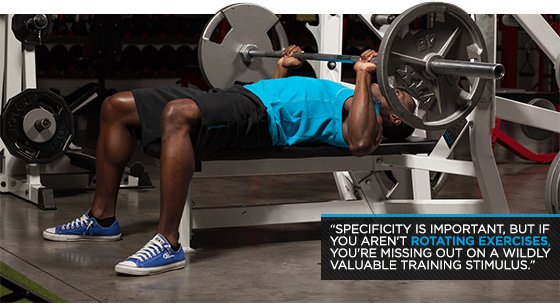

Mistake #3: Not rotating movements

It never ceases to amaze me when a guy claims that he just can't seem to add to his bench press (or any lift, for that matter), and when you ask him what he's done to work on it of late, and he tells you "bench press." Specificity is important, folks, but if you aren't rotating exercises, you're missing out on a wildly valuable training stimulus: rotating exercises.

While there is certainly a place for extended periods of specificity (Smolov squat cycles, for instance), you can't push this approach indefinitely. Rotating my heaviest movements was one of the most important lessons I learned along my journey. In addition to helping to create adaptation, you're also expanding your "motor program" and avoiding overuse injuries via pattern overload.

I'm not saying that you have to overhaul your entire program each time you walk into the gym, but there should be some semi-regular fluctuation in exercise selection. The more experienced you become, the more often you'll want to rotate your exercises. (I do it weekly). We generally rotate assistance exercises every four weeks, though.

Mistake #4: Inconsistency in training

I always tell our clients from all walks of life that the best strength-and-conditioning programs are ones that are sustainable. I'll take a crappy program executed with consistency over a great program that's only done sporadically. In my daily practice, this is absolutely huge for professional athletes who need to maximize progress in the off-season; they just can't afford to have unplanned breaks in training if they want to improve from year to year.

If a program isn't conducive to your goals and lifestyle, then it isn't a good program. That's why I went out of my way to create 2x/week, 3x/week, and 4x/week strength training options—plus five supplemental conditioning options and a host of exercise modifications—when I pulled my website together; I wanted it to be a very versatile resource.

Likewise, I wanted it to be safe; a program isn't good if it injures you and prevents you from exercising. Solid programs include targeted efforts to reduce the likelihood of injury via means like mobility warm-ups, supplemental stretching recommendations, specific progressions, fluctuations in training stress, and alternative exercises ("Plan B") in case you aren't quite ready to execute "Plan A."

I attribute a lot of my progress to the fact that at one point, I actually went over eight years without missing a planned lift. It's a bit extreme, I know, but there's a lesson to be learned.

Mistake #5: Wrong rep schemes

Beginners can make strength gains on as little as 40 percent of their one-rep max. Past that initial period, the number moves to 70 percent, which is roughly a 12-rep max for most folks. Later, I'd say that the number creeps up to about 85percent—which would be about a 5-rep max for an intermediate lifter. This last range is where you'll find most people who head to the web for strength training information.

What they don't realize is that 85 percent isn't going to get the job done for long, either. My experience is that in advanced lifters, the fastest way to build strength is to perform singles at or above 90 percent of one-rep max with regularity. As long as exercises are rotated and deloading periods are included, this is a strategy that can be employed for an extended period of time. In fact, it was probably the single (no pun intended) most valuable discovery I made in my quest to get stronger.

I'm not saying that you should be attempting one-rep maxes each time you enter the gym, but I do think they'll "just happen" if you employ this technique.