Prior to May 2016, the last time the U.S. Food and Drug Administration changed its nutrition-label design, a movie ticket cost $4, the average new car set you back about $13,000, and Beanie Babies hit the market. That was way back in 1993.

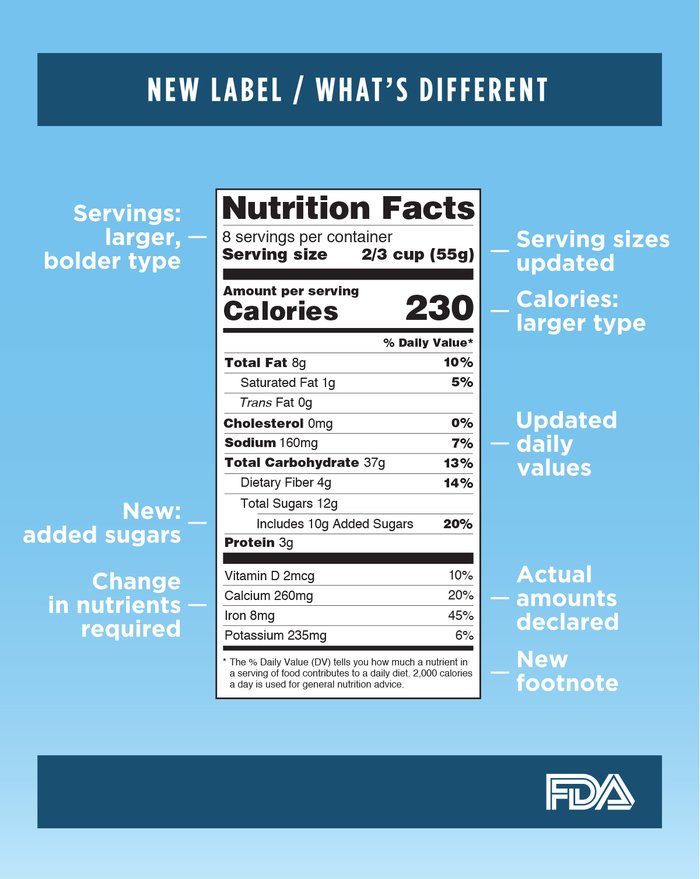

The label redesign, the FDA says, was based on "updated scientific information, new nutrition and public health research, more recent dietary recommendations from expert groups, and input from the public."[1] At first glance, the label changes may appear minimal. But they can help many consumers make better, healthier food choices.

Here are four major changes you should be aware of.

1. Large, Bold Font

If you asked 10 people what information they look for first on a nutrition label, you might get 10 different answers. Some might say fat, others calories, or cholesterol, or sodium. Based on its research, the FDA now uses large, bold type to call attention to what it has found to be the most important information: calories, then serving size, then percent of daily nutritional requirements.

To help guide consumers' eyes to the most important aspects of the label, the revised label features a bigger, bolder font for "serving size," "servings per container," and "calories per serving." This encourages consumers to pay attention to serving portions to keep their calories—and, ultimately, their weight—in check.

2. Updated Serving Sizes

Some manufacturers seem to care more about your wallet than your health, and bend labeling rules to sell more product. One strategy is to grab your attention by labeling some foods like low-fat ice cream and low-calorie peanut butter as "healthy choices."

But that "healthy" claim depends on unrealistic serving sizes. Sure, 1 gram of fat per "low-fat cookie" sounds great, but not if the cookie is the size of a dime.

The revised label relies instead on what the FDA considers "common" serving sizes. No longer will a 12-ounce or 20-ounce bottle of soda be considered two or three servings. People normally drink the whole bottle, so the label will list the whole bottle as one serving.

As the FDA notes, "serving sizes must be based on the amounts of food and drink that people typically consume, not on how much they should consume."

3. Added Sugars

There's a new kid on the nutrition-label block: added sugars, the amount of sugars artificially added to foods during production. By listing added sugars per serving, the FDA is highlighting the difference between sugars found naturally in foods (such as in fruit and vegetables) and those extra calories added to enhance flavor.

A consensus has formed that many people in developed countries consume too much added sugar. The U.S. FDA, the World Health Organization, and the American Heart Association all recommend people reduce the amount of sugar in their daily diet. This new label item can help.

4. New Nutrients Featured

The old food label included daily values for vitamins A, vitamin C, iron, and calcium. The new version now lists values for vitamin D and potassium, in addition to calcium and iron. Vitamins A and C are now voluntary, reflecting a successful FDA effort to reverse previously widespread deficiencies in these vitamins.

Vitamin-D deficiency, however, is still the most common nutrient deficiency in the United States.[2] Given that sunlight is the major source of vitamin D, many people would do well to just spend more time outdoors. But by drawing attention to vitamin-D values, the new label makes it easier for consumers to choose vitamin D-rich foods such as fortified dairy (milk, yogurt, cheese), egg yolks, mushrooms, salmon, tuna, and sardines.

The FDA added potassium values to the label because low dietary levels of this mineral can lead to increased risk for several chronic diseases.[3] Most fruits and vegetables are a good source of potassium. Excellent sources include oranges, avocados, tomatoes, potatoes, and bananas.

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (May 20, 2016). Changes to the Nutrition Facts Label. Retrieved from: http://bit.ly/changesnutritionfactslabel.

- Fulgoni, V. L., Keast, D. R., Bailey, R. L., & Dwyer, J. (2011). Foods, Fortificants, and Supplements: Where Do Americans Get Their Nutrients? Journal of Nutrition, 141(10), 1847-1854.

- Bazzano, L. A., Serdula, M. K., & Liu, S. (2003). Dietary intake of fruits and vegetables and risk of cardiovascular disease. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 5(6), 492-499.