We're all familiar with the "fast food will kill you, don't you dare touch that doughnut, put down the chips or your mother gets it" health mantras sung by fitness and nutrition experts. Those of us who are determined to follow a fit lifestyle find these nutrition "don'ts" simple, although sometimes difficult to follow. Often, we choose to "just say no." For some, "saying no" might not be an option.

According to new research that brings together psychology, physiology, and nutrition, food addiction may be a real thing. Studies that show how food affects addiction centers in the brain are rare and inconclusive, but good evidence suggests refined sugar, refined carbohydrates, and added fat, salt, and caffeine are addictive substances. For people who are addicted to refined foods, shaking their heads at a cookie jar full of Oreos isn't just difficult—it's impossible.

Actual food addiction, although at this stage still a hypothesis, may explain why people are repeatedly unsuccessful in their attempts to lose weight, or why they re-gain weight after working so hard to lose it. This evidence suggests that helping people solve their weight issues should include psychological therapy, along with an education in proper nutrition and activity.1

The Science of Addiction

Although it's no scientific certainty, several studies have located pathways in the brain that are activated by hyper-palatable food similarly to the way key reward pathways are triggered by drug or alcohol abuse.2,1,3,5,6 These studies found similarities in the down-regulation of dopamine receptors in obese people and meth abusers. Dopamine receptors mediate pleasure, so if the brain isn't getting the same kind of pleasure from a normal amount of drug use, the user needs more to feel good.3

In the possible case of food addiction, people with down-regulated dopamine receptors need more food to feel pleasure.9 Furthermore, a 2011 study found those with a higher BMI had smaller dopamine receptor density.

A 1999 study found that the brains of food addicts reacted to pictures of chocolate milkshakes in much the same way the brains of recovering cocaine addicts reacted to videos of someone smoking crack.7 Clearly, our brains have a more complex relationship with food than just that of energy provider and user.

What makes food addiction even more frightening is that, if you do need a toke, there's no need to hunt down a back-alley dealer for your fix. You can buy doughnuts or hot Cheetos and Takis anywhere—and you can buy them cheap.

Refined for Your Pleasure

It's the refining process makes food addictive.1 Sure, sugar and caffeine occur in nature—you can't eat a peach without also eating 13 grams of sugar. However, natural foods have much smaller concentrations of sugar, caffeine, fat, and salt than those that have been made in a laboratory. Much like refining cocaine from coca leaves, ethanol from grains, and opiates from poppies, natural substances are not addictive until they're extracted, concentrated, and added to food. Research says our brains are hard-wired to eat carbohydrate-rich food. Constantly consuming foods that have unnatural combinations and concentrations of carbs, fat, salt, sugar, and man-made chemicals may indeed turn us into junkies.

Other studies found that repeated overconsumption of refined foods may produce long term neuroadaptations in brain reward and stress pathways. These adaptations ultimately promote depressive or anxious responses when sugary noshes aren't available.8 Brain imaging has shown that high-sugar, high-fat foods work just like heroin, opium, or morphine on the brain. That means that the food we eat directly influences how our brain works. And just like alcohol or drugs, over-indulgence cements neurological pathways that connect the intake of food to obsession. If that's not creepy, I don't know what is.

You Are Your Environment

Craving Doritos does not necessarily mean your body needs carbs, or even that it's hungry. According to research, your environment can trigger food cravings.10,11 Just as a cured drug addict may relapse when he goes back to his old friends and hangouts, so can food cravings attack when we're in a specific place or feeling a certain way.12 Part of the reason we grow addicted is that our brains like to make connections. If we usually eat a hotdog at noon, our hotdog needs become paramount midday, every day. If we consistently eat dessert after dinner, it's likely that even if you're completely sated, you'll crave a bowl of ice cream.

This learning mechanism presents an interesting piece to the puzzle of food addiction. Perhaps our cravings are acquired responses: our environments and lifestyles influence the way our brains function. It's not that your body needs popcorn; it's the darkened theater, the smell, and the tradition that makes you buy it. Couple this with the actual chemical response that the extra salt and butter provokes in our brains, and we have an eating pattern that's difficult to smash.

Breaking the Habit

Even if you're not in the practice of lurking on street corners in hopes that someone will drop a half-eaten eclair into the garbage, you may have some unhealthy habits that revolve around food. These habit-breaking tips may help you avoid your daily ritual of walking to the vending machine for Funyuns and a Coke.

1 /// Create New Habits

Charles Duhigg, author of The Power of Habit, explains that your brain actually likes habits because they're efficient; your brain doesn't have to think so much.13 So, if you want to break a habit, give your brain a new one. That doesn't mean switch Snickers for Twix, but rather create what Duhigg calls a "cue, routine, and reward system." As soon as that afternoon craving for cookies hits, go for a walk, or head to the water cooler for some office gossip. Change the loop. With enough conscious effort, your brain will start to cue your new habit automatically—that means less thinking and less stress for you.

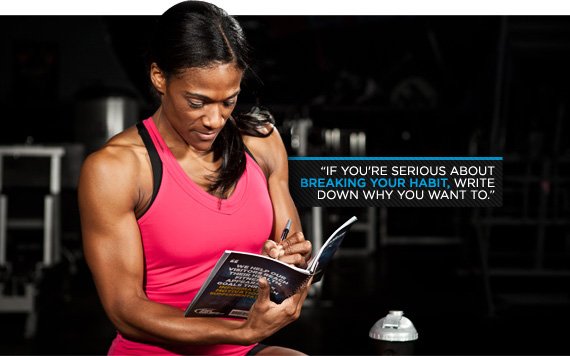

2 /// Write It Down

If you're serious about breaking your habit, write down why you want to. Janet L. Wolfe, a clinical psychologist and author, says that writing down the antecedents and the emotions of your habit can help make it more conscious14. If you eat emotionally, write down what you're eating and what you're feeling before and after you eat it. What craving is driving your routine? Making yourself aware of the reasons behind your addiction can help you push past it.

3 /// Reward Yourself

Choose a small goal. Every time you reach that goal, reward yourself. For example, if your small goal is to go an entire work week without hitting the vending machine, and you make it, reward yourself with a movie, bath, bike ride, or leave work an hour early on Friday. Healthy rewards make for healthy habits.

- Ifland, Preuss, Marcus, Rourke, Taylor, Burau, Jacobs, Kadish, Manso (2008). Refined food addiction: a classic substance use disorder. Medical Hypotheses 72: 518-526.

- Wang, GJ, Volkow ND, Logan J, Pappas NR, Wong CT, Zhu W, Netusil N, Fowler JS (2001). Brain dopamine and obesity. Lancet.357: 354-7.

- Small DM, Jones-Gotman M, Dagher A (2003). Feeding-induced dopamine release in dorsal striatum correlates with meal pleasantness ratings in healthy human volunteers. Neuroimage.19: 1709-15.

- Kalra SP, Kalra PS (2004). Overlapping and interactive pathways regulating appetite and craving. J Addict Dis 23: 5-21.

- Avena NM, Rada P., Hoebel BG (2008). Evidence for sugar addiction: behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake. Neruosci Biobehav Rev 32: 20-39.

- Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Flower JS (2001). The role of dopamine in motivation for food in humans: implications for obesity. Experit Opin Therap Target 6: 601-9.

- Gearhardt, Ashley N. Et. Al. (2011). Neural correlates of food addiction. Archives of General Psychiatry 68(8):808-16.

- Parylak Sarah L, Koob George F, Zorrilla Eric P (2011). The dark side of food addiction. Physiology and Behavior. 104:149-56.

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Folwer JS, Logan J, Jayne M, Farnceschi D, Wong C, Gatley SJ, Gifford AN, Ding YS, Papas N. (2002). Nonhedonic food motivation in humans involves dopamine in the dorsal striatum and methylphenidate amplifies this effect. Synapse 44: 175-80.

- Pelchat ML, Johson A, Chan R, Valdez J, Rgland JD (2004). Images of desire: food craving activation during fMRI. Neuroimage.23: 1486-93.

- Gibson EL, Desmond E (1999). Chocolate craving and hunger state. Appetite. 32: 219-40.

- O'Brien CP, Childress AR, Ehrman R, Robbins SJ (1998). Conditioning factors in drug abuse: can they explain compulsion? J Psychopharmacol. 12:15-22.

- Duhigg, Charles. (2012). The Power of Habit. New York: Random House

- http://www.webmd.com/balance/features/3-easy-steps-to-breaking-bad-habits