Bodybuilders and fitness models rely on well-balanced diets that include a variety of fish and seafood to help attain their physical goals. Many types of fish and seafood are extremely low in fat, making them an appropriate, high-quality source of animal protein. Even fattier cuts of fish offer benefits for general health and athletic performance because they contain heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acids.

A diet that includes fish and seafood is good for bodybuilders and models. Evidence also shows that eating fish can promote a healthy pregnancy, enhance brain and eye development of the fetus, aid thinking and learning during childhood, and slow mental decline as people age10. Fish also provides a significant source of vitamin D and other valuable minerals, including selenium, iodine, magnesium, iron and copper.8

But there's a catch: All seafood contains mercury, a naturally occurring chemical element that can be harmful to humans. With the threat of mercury in fish and seafood, do athletes need to be concerned? Let's fish for answers to some frequently asked questions on the subject.

Mercury in the ocean can be naturally occurring from environmental sources1 such as mineral deposits, underwater vents and volcanoes. Manmade sources include industrial pollution1, most notably from coal-fueled power plant emissions. Coal contains mercury as a natural contaminant, and the process of burning it to generate electricity can release mercury vapors into the atmosphere. Mercury then falls from the air into lakes, rivers, streams and oceans through rain, snow and runoff.3

Microorganisms in the water aid in the transformation of mercury into toxic methylmercury.2 Methylmercury is absorbed by algae, which is in turn eaten by fish and other organisms throughout the food chain.

Larger and longer-living fish higher in the food chain accumulate greater concentrations of mercury because they consume a large volume of prey containing lower mercury concentrations.2

Small, short-living fish such as salmon, cod and trout have low levels of mercury. Large, long-living predators such as shark, swordfish, golden bass, king mackerel, and tilefish have the highest mercury levels.4

The most commonly-eaten species available in North America (such as shrimp, canned light tuna, salmon, and pollock) are generally low in mercury and pose little risk to most people.10 According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the risk of mercury exposure from eating fish and shellfish is not a health concern for most people.1

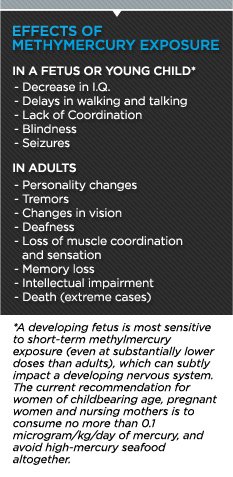

But even a slight risk warrants attention; high levels of methylmercury can potentially harm human health.8 It's readily absorbed into the bloodstream and distributed throughout the human body, including the brain.8

Very high methylmercury exposure resulting from accidents (eg. Minimata), or prolonged high intakes of fish species containing high levels of mercury for more than 10 years can result in sensory-motor symptoms in adults which are typically reversible when the mercury exposure is reduced.10 Bear in mind the severity of these health effects largely depends upon the magnitude and duration of the methylmercury exposure.8

Methylmercury can be particularly harmful to pregnant women and can impact the nervous system during normal fetal development and childhood.5 That's why pregnant and nursing women, and women trying to get pregnant, infants, and children should limit their intake of mercury.5

Very high methylmercury exposure or regularly ingesting large amounts of fish containing high levels of mercury for more than 10 years can result in sensory-motor symptoms in adults. Fortunately, these symptoms typically reverse when the mercury exposure is reduced.10

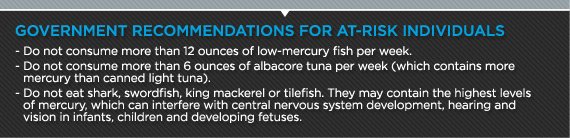

In March 2004, the FDA and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced their revised consumer advisory on fish and mercury consumption. Their recommendations included the following for pregnant women, women trying to become pregnant and young children:

The same recommendations should be followed when feeding fish and shellfish to young children, except smaller portion sizes should be served.1

Nope. Cooking or cleaning seafood does not reduce its mercury levels.3,6

Methylmercury contamination varies widely from region to region.5 The FDA and EPA recommend you check state advisories about the safety of fish caught by individuals in local lakes, rivers, and coastal areas. If no advice is available, eat up to 6 ounces per week of fish you catch from local waters, but do not consume any other fish during that week.1,5

In Canada, The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) conducts routine monitoring of the mercury levels in numerous fish species at fish processing plants before the fish are taken to commercial markets.8 A summary of this data is provided in Health Canada's health risk/benefit assessment document on mercury in fish.

Tuna mercury levels can vary depending upon the type of tuna and where it was caught. Tuna steaks and canned albacore tuna generally contain higher levels of mercury than canned light tuna.3 This makes sense considering albacore is higher on the food chain than the smaller tuna species that are processed for light tuna.

Unlike albacore, "light" tuna refers to any one of the following types of tuna: skipjack, bluefin, yellowfin or tongol.8 Skipjack is the best choice among these light tuna options for lowering your risk of mercury exposure.9

Canned tuna provides a convenient, portable and inexpensive source of protein. Canned tuna packed in water contains a higher omega-3 fat content than oil-packed tuna.9 When buying canned albacore, it's good to choose a water-packed premium wild Pacific albacore from a reputable supplier that tests mercury levels. Although more expensive, specialty brands of canned tuna offer more omega-3 fatty acids, more sustainable fishing methods and higher-quality production methods.

Long chain omega-3 fatty acids, called docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), known as "fish oil," has been reported to have favorable neurological and cardiovascular effects that outweigh the neurological risks of mercury toxicity.10

Purified fish oil supplements offer omega-3 fatty acids with lower levels of contaminants.3 Fish oil capsules contain 20-to-80 percent of EPA and DHA by weight, little to no mercury, and variable levels of PCBs and dioxins.10 The exposure to PCBs and dioxins is low given the small amounts of fish oil consumed.10

Supplements can provide an alternative option for those who do not wish to consume fish. Test results for various fish oils can be reviewed on the International Fish Oil Standards Website.

In a word, no: Don't eliminate seafood from your diet. The benefits of modest fish consumption (1-2 servings per week) outweigh the risks among adults and women of childbearing age (excepting a few selected species of fish such as shark, swordfish, king mackerel and tilefish).10 Evidence also suggests that fish consumption and the associated intake of EPA and DHA from fish can help maintain healthy heart function.

Fish and shellfish are an important part of a healthy diet. By making informed choices about which types of fish you consume and how often, you can reap the health benefits while minimizing mercury exposure.

*For further information about the safety of locally caught fish and shellfish, visit the Environmental Protection Agency's Fish Advisory website or contact your State or Local Health Department. For information on EPA's actions to control mercury, visit EPA's mercury website. 1

References

- What You Need to Know About Mercury in Fish and Shellfish. March 2004 EPA and FDA Advice For: Women Who Might Become Pregnant Women Who Are Pregnant Nursing Mothers Young Children. www.fda.gov

- Learned, Nicole. Myths and Realities: The Fishy Truth about Mercury Toxicity. Faculty Peer Reviewed (NYU Langone Medical Center). December 17, 2011. www.clinicalcorrelations.org

- Methylmercury in seafood. Information and Education. © 2010 Whole Foods Market.

- Mozaffarian D, Rimm EB. Fish intake, contaminants, and human health: evaluating the risks and the benefits. JAMA. 2006:296(15):1885-1899. jama.ama-assn.org

- Levenson CW and Axelrad D. Too much of a good thing? Update on fish consumption and mercury exposure. Nutrition Rev (2006) 64: 139-145. www.dmaxelrad.com

- Harris HH, Pickering IJ, George GN. The chemical form of mercury in fish. Science. 2003:301(5637):1203. ukpmc.ac.uk

- www.americanpregnancy.org

- Health Canada: Mercury in Fish: Questions and Answers: www.hc-sc.gc.ca

- What is the Best Tuna to Buy? whfoods.org

- Mozaffarian D, Rimm EB. Fish intake, contaminants, and human health: evaluating the risks and the benefits. JAMA. 2006:296(15):1885-1899. jama.ama-assn.org

- Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference-Release 18 (2005). Washington, DC: US Dept of Agriculture; 2006.