Let's play a quick game of fill-in-the-blanks. Simply add the missing words to these sentences:

Manufacturers of [blank] are not required to conduct research on safety and effectiveness of their product. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) must prove a [blank] is unsafe before it can be taken off the market.

I know what you're thinking: "No-brainer. The answer is clearly 'dietary supplements.'" And sure, that's one correct answer. However, another is "all the groceries in your cart and food served to you at Anywhere Restaurant USA." A third would be "almost every beverage you buy."

Foodborne outbreaks send thousands of Americans to hospitals and handfuls to the grave each year. And frankly, such serious adverse events are comparatively rare from consuming supplements. But the response to the two phenomena couldn't be more different. Foodborne illnesses get treated as one-offs, or problems within specific companies, while critics of supplements call for the wholesale elimination of—or at minimum, avoidance of—the entire industry.

So, which class of nutritional item is subject to more regulation, and has more "wiggle room" for the unscrupulous to take advantage of? The answer might surprise you. Let's dig in and talk frankly about the differences between food and supplements, and what they should mean for you in your quest to be as healthy and risk-free as possible.

How Dangerous Is Your Dinner?

The chances are significantly greater that a person will become sick, hospitalized, or buried six feet under from eating food bought at the grocery store or a restaurant than from consuming a dietary supplement.

How big is the risk? I'll break down the stats a little later in the article, once you have some more context in which to understand them. But anecdotally, nearly all of us can remember getting food poisoning at least a few times in our lives. More officially, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which among its many vital roles investigates food poisonings, reported that in 2016 alone, they monitored between 21 and 57 "potential food poisoning or related clusters each week, and investigated more than 200 multistate" outbreaks, which led to the recalls of a wide range of foods, such as packaged salad and frozen vegetables.

More recently, among the many foodborne outbreaks that occurred in 2018, a nationwide E. coli outbreak from lettuce killed 5 people and sickened close to 200. Of those who were made ill, 89 required hospitalization and about 26 developed a life-threatening form of kidney failure. Just as that preventable food-safety outbreak was ramping up, a salmonella outbreak linked to eggs caused 11 people to be admitted to hospitals and at least another 24 people to become seriously ill across 10 states. Weeks later, another salmonella outbreak linked to pre-cut melons caused dozens of people to be hospitalized and more than 70 people to become sickened across at least eight states. That was just in the first half of the year. On June 15, 2018, the CDC posted yet another salmonella outbreak that sickened 73 people across 31 states. The source? Kellogg's Honey Smacks cereal.

Now imagine that a supplement caused such widespread and serious problems. Media reports wouldn't just be reporting on the recall and warning people to avoid the tainted product. Instead, the whole industry's quality and safety would be brought into question—even more than usual. We'd hear the same-old half-truths and blatant untruths about how supplements aren't regulated (they are), and how all supplements are unsafe or bad for you (they aren't.)

Adverse Event Reporting: A Free Pass for Foods

Unless you're deep into the world of supplements, you might not know that when it comes to reporting problems, supplements are actually regulated more like drugs than like foods. For example, dietary supplement companies, like drug companies, are required to report all serious adverse events to the FDA within 15 days of being notified of a potential consumer incident.

It's important to note here that the product doesn't actually have to cause the incident. Rather, if the consumer was taking, was known to take, speculated to have been taking, or if the product is simply mentioned at all by the person reporting a potential serious adverse event, then that product becomes part of a serious adverse event report and must be investigated thoroughly.

The obvious question here: What constitutes an "adverse event?" It definitely doesn't have to be anything as severe as food poisoning. The FDA predictably identifies an adverse event as "'any health-related event…that is adverse." It includes pretty much any user grievance about quality, including "complaints about off taste or color… defective packaging, and other non-medical issues." All non-medical adverse events have to be thoroughly investigated and records maintained for at least six years after the incident occurs.

Adverse events that involve a person requiring medical attention or resulting in death are classified as "serious adverse events" and must be reported to the FDA within 15 days of receiving notification of the event, and similarly must be thoroughly investigated and records maintained for at least six years after the company is first informed of the incident. Plus, during the year after the serious adverse event is first reported, the company must report to the FDA any "new information" that pertains to the serious adverse event, such as a change in health of the person involved, clinical study findings, or other adverse events that could be related.

To give a more tangible example of an everyday adverse event that must be recorded and investigated, imagine a customer calls and complains that they purchased a jug of protein and the product smelled and tasted so bad it made them want to throw up. That could be because it was spoiled or expired, sure, but it could also simply be because the user ordered an unflavored vegetable protein and weren't prepared for the reality of how it tasted and smelled. In either case, the product quality complaint would likely be filed as "Adverse event non-serious: nausea," investigated by the company's Quality Assurance department, and records maintained and made available to the FDA for the next six years.

Think the same would apply if, say, you cut open one of those cute little tangerines and found something truly nasty inside? The FDA is clear: "The requirements…do not apply to foods."

Food Standards vs. Supplement Standards

In 2017, a well-publicized research paper published in the Journal of Medical Toxicology generated a lot of negative press about supplements. The researchers showed that the number of adverse events involving dietary supplements and reported through the National Poison Data System from 2005 through 2012 had jumped 49 percent. What horror!

Just look at the headline, and the ensuing coverage, and the takeaway seems clear: Supplements are getting more dangerous. But the opposite was the case: This study seems to indicate that the government regulations were working to increase industry compliance and transparency.

The reason is that 2007 was the first year wherein dietary supplements were being held to a good-manufacturing-practices (GMP) standard very similar to those of the pharmaceutical industry. That includes the mandatory reporting of all potentially serious adverse events. By 2010, the dietary supplement GMPs were required industrywide.

An increase in adverse event reports during this time shouldn't have come as a great surprise! It was simply a sign that more companies within the dietary supplement industry are abiding by the laws explicitly, ensuring a higher-quality standard and greater safety transparency.

Speaking of GMPs, you'll probably be surprised to learn that companies marketing food products are under no requirement—none—to validate their formulations through analytical testing of the identity, purity, potency, or composition of the raw materials they use in their products, or the quality of their finished products before those products are released for resale to you, the consumer.

Are they regulated? Yes. But to the level of dietary supplements? Not even close. Section 110.19 of the Federal Register even goes as far as exempting facilities that process and package raw agricultural commodities from having to adhere to minimal processing standards altogether.

Supplement-industry critics likely believe there are higher quality standards for raw vegetables, fruits, nuts, and seeds—exactly the kinds of raw commodities that are commonly the source of widespread and repeated foodborne outbreaks. Sorry, there aren't.

Both conventional foods and dietary supplements are also subject to the tenets of the Food, Drug, & Cosmetic Act (FD&C), which is meant to ensure the quality of products sold as foods. But since 2007, the standards between the two have been very different. The rules for supplements require significant analytical testing of all raw materials, as well as testing of the finished products, before they can be released for resale to consumers. Products sold as conventional foods and beverages aren't held to this higher level of quality assurance and control.

In fact, Title 21 of the FD&C Act clearly states, "No definition and standard of identity and no standard of quality shall be established for fresh or dried fruits, fresh or dried vegetables, or butter." That means that food companies are under no requirement to test the ingredients they use or their finished products for:

- heavy metal concentrations

- pesticides and pesticide residues

- microbiological organisms such as E. coli or salmonella

Neither are they required to properly validate the ingredients used, nor the accuracy of the Nutrition Facts panel they use to market the product—that you probably read to help choose between products in the store.

Dietary supplement GMPs, on the other hand, absolutely require ingredient validation and finished product testing before they're used within a formula or released for resale, respectively. As I explained in my article "Are My Vitamins and Supps Safe After the Expiration Date?" if a dietary supplement includes a "Best By" date, then stability testing must also be conducted and documented to show that the product will retain at least 90 percent potency and nutritional profile through that date.

In tangible terms, this means that if you want to sell crackers, there's plenty about your product that regulators will simply trust—with no evidence to back it up—to be accurate and safe. A simple jug of whey protein powder has a much higher bar to meet before, and after, hitting the shelves.

Food vs. Supplements: The Stats

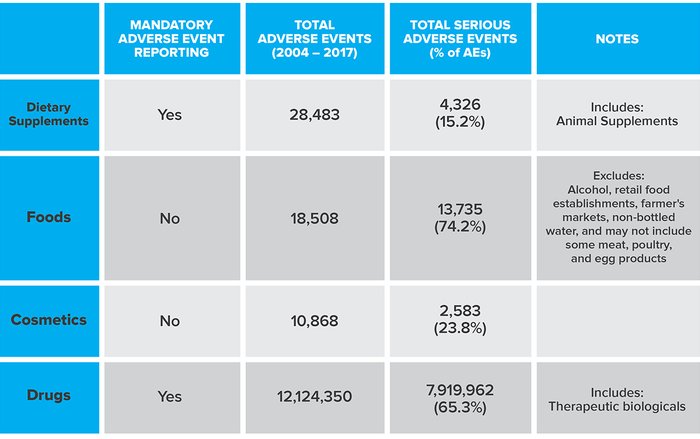

Now that we've discussed both what constitutes an "adverse event" and the general standards that supplements and food are respectively held to, we can pull back and take a more informed look at the stats of how many people are having reportable bad experiences with each one. This comes from the FDA's open FDA website, a searchable database, and represents all the reported adverse and serious adverse events between 2004 and 2017 for FDA-regulated products.

Source: FDA's openFDA website

A few points worth filing away:

- Only those companies that market drugs and dietary supplements are required to report potentially serious adverse events. Food and cosmetics? Nope.

- Animal supplements fall under the same general umbrella as supplements for human use. So this weighs the scales against supplements at least a little bit.

- Because foods and cosmetics aren't required to report potentially serious adverse events, their actual events are probably significantly higher than is being reported.

Supplements actually come off pretty well here. The number of total events is higher than foods, but the percentage of serious adverse events is far lower. I consider this an endorsement of the adverse events reporting system. It significantly reduces the likelihood of quality-related adverse events, and can help identify a problem quickly to reduce the risk of it affecting more consumers. Plus, with mandatory reporting, the root cause can be more expeditiously identified and corrected.

Don't Believe Everything You Read

As I mentioned in my article "Are Supplements Regulated? Yes. Here's How," I'm quite aware that not every dietary supplement company follows the laws and regulations. But neither does every licensed car owner follow all the rules of the road. Plenty of them do, and the ones who do shouldn't be cast in the same light as the scofflaws. Accusing all dietary supplements of being of questionable quality is as unfair as accusing all drivers of being out-of-control law breakers.

The good news is that laws do in fact exist when it comes to dietary supplements, and there is a solid framework in place to enforce those laws. What's more, the data supports that supplement safety isn't the serious public hazard the industry's critics project it to be.

I'm not saying you should avoid food and take only supplements instead. Whole foods should absolutely take up the vast majority of your nutrition. And yes, you should absolutely be careful and judicious when buying supplements. But don't make the mistake of thinking that what's on the plate doesn't deserve the same criticism as what's in the scoop or capsule.