Imagine how American society would function if drug dealers pumped 150 to 175 pounds of heroin per person per year into the veins of the elderly, the middle-aged, and the young alike. Legally. Well, sugar, an addictive substance that speeds along the same brain pathways as heroin, enters the food supply in those quantities. The result of this sugar surge is that more than one in three adults now has either Type 2 diabetes or its harbinger, pre-diabetes. Include those under age 18, and 105 million Americans are harboring a life-threatening blood-sugar disorder.

As with any addiction, the sugar situation will only worsen barring drastic intervention and widespread lifestyle changes. Consuming too much sweet stuff is lighter fluid for Type 2 diabetes, and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that by 2050, the disease, in its full form, will inhabit as many as one in three U.S. adults. Add in the far more numerous pre-diabetics, and you may be hard-pressed to find anyone with healthy glucose metabolism by the middle of the 21st century.

Many of these blood-sugar cripples won't be capable societal contributors. They may be little more than sugar smack-heads. They'll bankrupt our healthcare system with their chronic fatigue, dialysis treatments, amputations, and the numerous other diabetic complications. A society with such an overwhelmingly diabetic population will no longer be viable economically, a much scarier prospect than that predicted in the dystopian novel Brave New World, where addicts merely crave the comparatively less harmful Soma and then go do their assigned tasks.

Most Americans keep right on eating and drinking boatloads of sugar because, after all, they're sugar junkies. I witnessed this phenomenon when I saw my father for the first time in 20 years in early 2008. He was lying in a hospital bed looking nearly cadaverous. His entire right leg had been amputated; his teeth had disintegrated amidst swollen gums. Despite this wretched condition, his mood brightened only when orderlies wheeled in a meal of mashed potatoes (along with chicken) and fruit, both of which quickly convert to glucose in the bloodstream. His fix had arrived. He was dying of diabetes, and yet his "caretakers" were still pumping him full of diabetes-friendly carbohydrates.

Sugar Nation - Official Book Trailer

Watch The Video - 02:47

What's more, my father openly longed for the bottle of root beer that was stashed away in a cabinet across the room, a scene I describe in Sugar Nation: He still indulged this diabetic's poison even knowing that too much sugar cost him part of his body. This scene reminded me of a drug addict who has seen his life destroyed by the substance he can't refuse. Only the worse off he becomes, the lousier he feels, the more he craves the very thing that sentenced him to this hell on earth.

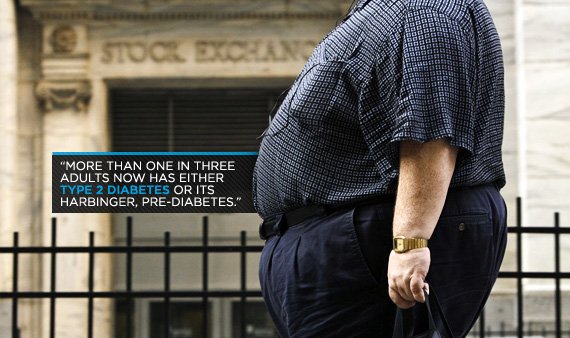

How can the white stuff that kids and adults alike sprinkle on their cereal have this narcotizing power? Researchers at Princeton University have studied the effects of sugar on the brain chemistry of rats, and what they've found is that their subjects exhibit all the effects of heroin addiction. Sugar does this by triggering the release of the feel-good brain chemical dopamine in the section of the brain normally associated with addictive behaviors. The dopamine release produces a drug-like "high." Yet the brain adapts. So it takes more of the substance—in this case, sugar—to produce the same effect.

According to lead researcher and Princeton psychologist Bart Hoebel, PhD, "Our evidence from an animal model suggests that bingeing on sugar can act in the brain in ways very similar to drugs of abuse."

Lessening the sugar stimulation only makes the body want more dopamine. Remove the substance altogether, and the sugar abuser experiences physical and psychological withdrawal symptoms. The body is addicted. Twinkies aren't classified as a controlled substance, but for the glucose intolerant, perhaps they should be.

But there's more to it in the case of my father and the rest of us who have reactive hypoglycemia, an underreported pre-diabetic condition in which blood sugar spikes in response to a heavy carb load. Then the pancreas overreacts by secreting too much insulin, too late, like an over-eager rookie cop coming across a crime scene after the fact. This insulin response drives blood sugar below 70 milligrams per deciliter, making your body crave quick-energy sugar not just for pleasure but also for survival. At this point, it's not just your brain that's craving glucose; cells throughout your body demand it, too.

I'd challenge anyone to find a drug whose effects are more powerful than a blood sugar drop from 160 to 50 in half an hour—the scale of my descent on a glucose tolerance test when I learned that I was pre-diabetic. Before I learned to avoid the sugar trigger, fatigue didn't set in gradually; it hit with a whoosh. I felt as though I'd been shot by a tranquilizer capable of taking down an elephant in the wild. I've never taken narcotics recreationally, but I have used Vicodin after surgeries, and the feeling of that drug reminded me of a carb-induced blood-sugar crash. If that prescription pain med came in the form of a jelly doughnut, rather than a pill, you'd have some idea of the hold sugar had on me during childhood and throughout much of my adult life.

The good news is that there are simple rehab solutions to sugar addiction. I know, based on personal experience. Breaking the cycle means avoiding crashes. To do this, you need to eat protein, healthy fats, and fibrous vegetables for breakfast, a meal normally stocked with simple sugars and other fast-acting carbohydrates. Know the code names that are used to disguise sugar on food labels:

- dextrose/maltodextrin

- fructose

- fruit juice concentrate

- glucose

- high fructose corn syrup

- honey

- maple syrup

- molasses

- sucrose

- xylose

Avoid the foods whose packages list them. Better yet, switch from packaged to whole foods. Exercise daily, which not only helps usher sugar out of your bloodstream, but also produces good-vibe brain chemicals of its own, called endorphins.

So, we can change our fate. We know what to do to prevent this epidemic that will cripple us as individuals and as a society. But the question is: Will we take action before it's too late?

Republished with permission from kriscarr.com.