A few years back, I fell in love with a hill. Actually, "hill" might be an overstatement. She was more like a pimple on the shoulders of some other, taller hills about 10 minutes from my house. Steep hiking trails climbed her from four sides, each one about a 10-15 minute run or a 25-minute walk from road to summit. The first time I tried to run up her east face, I crapped out about halfway up and started walking—and hawking up pulmonary antiquities. The third time, I made it to the top, though I suspected it might cost me my life.

It didn't. So I came back the next day, and the next. The spitting and cursing continued, and my goal was always the same: Don't stop running until the summit, even if "running" is slower than walking. I began to visit the hill obsessively, no matter the weather or what else was going on in my life. Whenever I was nearby, I made a point to stop and do what I called "the chores." I knew how much time these sojourns required, and I knew I could justify that time and plan for them.

It was always intense and difficult, but it didn't take long for me to begin looking forward to visiting "Hilly McBitch," as I came to call her. (As far as I know, she wasn't important enough to have earned an official name). I judged myself harshly for my efforts, but not in terms of mileage time; to this day I don't know how far it is to the top, and I never used a stopwatch. If I was honest with myself, I simply knew whether I had done a good job. When I didn't, I let myself feel authentically—and momentarily—ashamed. Then I said I'd do better next time.

At some point—I forget exactly when—I stopped feeling drained when I came off the hill, and instead found myself feeling energized and poised. That feeling carried over into everything I did through the day, from work to washing the dishes. My temperamental lower back stopped making its presence known. I slept better at night and relished refueling at mealtime. I had undergone a transformation of sorts, even though before-and-after pictures wouldn't have shown much of a difference.

Why Would Anyone Do That To Themselves? ///

What had happened? I had picked a difficult, transformative activity and worked it into my everyday life—not just my gym routine—in small doses, and got incrementally better at it. I set myself up for dozens of small, fleeting triumphs, rather than hinging my hopes on occasional climactic ones.

In his book The Naked Warrior, Pavel Tsatsouline calls this model of frequent, informal practice "greasing the groove." In a recent article, trainer Ben Bruno called it "paying the toll," a term which I prefer. It makes instant sense in the context of everyday life, and avoids the suspicious looks that happen when you tell someone you've gotten stronger by greasing the groove twice a day.

Whatever you call it, the idea is the same. If you want to get better at something, Pavel writes, "You must do it often, do it a lot, and do it to the exclusion of other things." He tells the story of record-setting powerlifter Dr. Judd Biasiotto, who set up a bench in his kitchen and "got in the habit of hitting it every time he was in the area." That's an extreme example from an elite athlete, but the model is equally applicable for someone who, like me, was trying to experience initial fitness breakthroughs.

What these writers are describing isn't a "workout" per se. It's more like a practice, which a word Tsatsouline uses often. It's not hanging a pull-up bar in your doorway to do as many pull-ups as you can manage once a day; it's hanging the bar to do a few pull-ups 3-4 times a day. In this model, you don't work yourself to exhaustion or muscle failure regularly. On the contrary, you leave plenty in the tank and walk away feeling "fresh as a cucumber," in Pavel's words. After all, do you give all your change to the toll clerk on the morning commute? Of course not, because you know you'll be passing by again in the afternoon.

Any non-equipment-intensive exercise you're struggling to master is candidate to become "the chores." Hill sprints were my choice, because I wanted improve my running form, endurance, and leg strength.

Clearly, You've Lost It ///

I kid about the flame. But in all seriousness, Mr. Bickle does have something to teach us here. Namely, it's to be expected that your personal "toll" strikes your loved ones—and even you, at first—as utterly demented. This is normal, and you must embrace it. Give your implement a name. Feel weak in its presence, and aim only to stop being so pathetic. If muttering "iron sharpens iron" or "pain is the cleanser" helps you along, great. You were probably too sane to begin with.

If that doesn't turn off the voice saying, "Why on earth would I willingly subject myself to that," then let's address the pain for what it is. Hill sprints and full-ROM-pull-ups suck—and yes, they do suck—in ways that are more immediate and avoidable than anything else you'll encounter in your day (hopefully).

Choosing to battle with them, and knowing that another battle is just over the horizon, makes life's normal obstacles seem more manageable by comparison. This is a payoff that strength training can give you right now, not far off in the future.

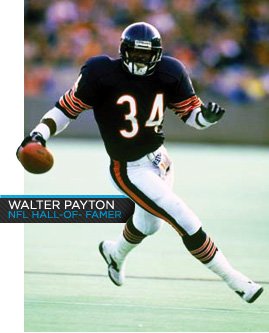

One great athlete who knew this was the legendary Chicago Bears running back Walter Payton. He haunted a series of hills throughout his career, the most famous of which—now designated as "Payton Hill"—was just a quick jaunt from his home in Arlington Heights, Illinois, during the 1980s. It was located in a landfill, and Payton sometimes had to kick trash aside as he ran, but he described his heap in reverent tones in interviews. It was a "goal-setter," he said; a "will-maker." My personal favorite: "It's a mother." "Sweetness" wore his training style on his sleeve, running the hill sometimes 20 times in a row.

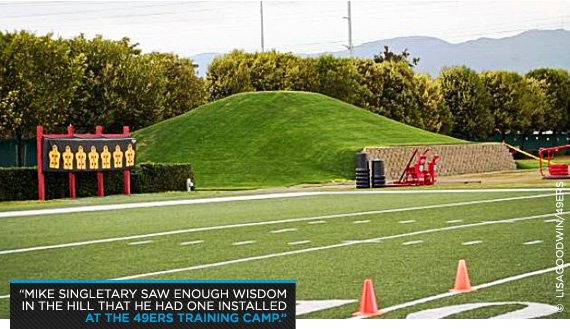

He welcomed his teammates to test themselves against it. They puked—luckily, it was a dump to begin with. But one of them, Mike Singletary, saw enough wisdom in the hill that he had one installed 25 years later at the San Francisco 49ers training camp when he was a coach for that team. "There's something about the hill," he said at the time. "It's beautiful to look at. It's going to bring about something you can't really get in the weight room or on the track."

Son of Hilly ///

So the moral of the story is to train like Walter Payton, right? Ye gods, no. Walter Payton's day job was trying to avoid death-by-300-pound-lineman, and his training was intimately tied to that goal. He once described his fitness philosophy succinctly as, "What I try to do is kill myself." That doesn't sound "fresh as a cucumber" to me—and I hate cucumbers.

No, the lesson is to find what makes you humble, and get to know it intimately. A hill is an easy choice, because as Payton said, "It's already there." Dirt-bumps are free and plentiful, and they're impossible to misplace, break, or accidentally sell in a garage sale. Almost all of them offer a view from the top, which is a bigger reward than it sounds.

Since my initial dalliance with Hilly, I've moved to the other side of town and only visit her once a month at best. Try as I might to replace hills with gym workouts, I never found what felt like an adequate replacement until just recently. My new tormenter, Hillton McBitch, is a short, steep zig-zag about 50 yards long that climbs up a bluff half a mile from my house. Google Maps doesn't recognize Hillton, but my body does, with a familiar combination of dread and nausea that lets me know I've been comfortable for too long.

He's there right now... waiting for me. I should go.