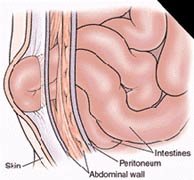

Several different types of abdominal wall hernias exist, along with a larger number of eponyms for these various types. This article reviews the pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment of most of these hernias from an emergency medicine perspective and discusses the various surgical procedures used to repair them. Hernias are brought to the attention of an emergency physician either during a routine physical examination or when the patient has developed a complication associated with the hernia.

Several different types of abdominal wall hernias exist, along with a larger number of eponyms for these various types. This article reviews the pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment of most of these hernias from an emergency medicine perspective and discusses the various surgical procedures used to repair them. Hernias are brought to the attention of an emergency physician either during a routine physical examination or when the patient has developed a complication associated with the hernia.

Pathophysiology:

Indirect Hernia

- An indirect inguinal hernia follows the tract through the inguinal canal. Differentiating a direct hernia from an indirect hernia requires familiarity with boundaries for this passage.

- The canal begins in the intraabdominal cavity at the internal inguinal ring (located lateral to the inferior epigastric arteries, approximately midway between the pubic symphysis and anterior iliac spine). The canal courses down along the inguinal ligament. The external ring of the canal is located medial to the inferior epigastric arteries, subcutaneously and slightly above the pubic tubercle. Contents of this hernia then follow the tract of the testicle down into the scrotal sac.

Direct Hernia

- A direct inguinal hernia usually occurs because of a defect within the boundaries of an area called the Hesselbach triangle. This triangle is defined inferiorly by the inguinal ligament, superolaterally by the inferior epigastric arteries, and medially by the conjoined tendon.

Femoral Hernia

- This hernia follows the tract below the inguinal ligament through the femoral canal. The canal lies medial to the femoral vein and lateral to the lacunar (Gimbernat) ligament.

- Because femoral hernias protrude through such a small defined space, they frequently become incarcerated or strangulated.

Umbilical Hernia

- This hernia occurs through the umbilical fibromuscular ring, which usually obliterates by 2 years of age.

- Umbilical hernias are congenital in origin and are repaired if they persist in children older than 2-4 years.

Richter Hernia

- This hernia occurs when only the antimesenteric border of the bowel herniates through the fascial defect.

- If the entire circumference of the bowel is not incorporated in the hernia, the bowel may not become obstructed, even if the hernia is incarcerated or strangulated. A Richter hernia involves only a portion of the circumference of the bowel. As such, the bowel may not be obstructed, and the patient may not present with vomiting. Richter hernia can occur with any of the various abdominal hernias. It is particularly dangerous, as a portion of strangulated bowel may be reduced unknowingly into the abdominal cavity, leading to perforation and peritonitis.

Incisional Hernia

- This iatrogenic hernia occurs in 2-10% of all abdominal operations secondary to breakdown of the fascial closure of prior surgery. Even after repair, recurrence rates are high, approaching 20-45%.

Spigelian Hernia

- This rare form of abdominal wall hernia occurs through a defect in the spigelian fascia, which is determined by the lateral edge of the rectus muscle at the semilunar line.

Obturator Hernia

- This hernia passes through the obturator foramen, following the path of the obturator nerves and muscles. As the canal is larger in diameter in females, this hernia occurs with a female-to-male ratio of 6:1. Because of its anatomic position, this hernia presents more commonly as a bowel obstruction than as a protrusion of bowel contents.

Reducible Hernia

- This term refers to the ability to return the contents of the hernia into the abdominal cavity, either spontaneously or manually.

Incarcerated Hernia

- An incarcerated hernia is no longer reducible. Vascular supply of the bowel is not compromised. Bowel obstruction is common.

Strangulated Hernia

- A strangulated hernia occurs when vascular supply of the bowel is compromised secondary to incarceration of hernia contents.

Frequency

Mortality/Morbidity: Morbidity is secondary to missing the diagnosis of the hernia or complications associated with management of the disease.

Race: Umbilical hernias occur 8 times more frequently in black infants than in white infants.

Sex:

Issues Must Be Considered:

- Asymptomatic hernia

- Presents as a new lump in the groin (or site of the hernia)

- Aching sensation (radiates into the area of the hernia)

- No true pain or tenderness upon examination

- Enlarges with increasing intraabdominal pressure and/or standing

- Incarcerated hernia

- Painful enlargement of a previous hernia or defect

- Cannot be returned (either spontaneously or manually) through the fascial defect

- Nausea, vomiting, and symptoms of bowel obstruction (possible)

- Strangulated hernia

- Symptoms of an incarcerated hernia present combined with a toxic appearance.

- Systemic toxicity secondary to ischemic bowel is possible.

- Strangulation is probable if pain and tenderness of an incarcerated hernia persist after reduction.

- Suspect an alternative diagnosis in patients who have a substantial amount of pain without evidence of incarceration or strangulation.

- Femoral hernia: Medial thigh pain as well as groin pain are possible because of the position of this hernia.

- Obturator hernia

- Because this hernia is hidden within deeper structures, it may not present as a swelling.

- Instead, patient may complain of abdominal pain or medial thigh pain, weight loss, or recurrent episodes of bowel or partial bowel obstruction.

- Pressure on the obturator nerve causes pain in the medial thigh that is relieved by thigh flexion. This same pain may be exacerbated by extension or external rotation of the hip (Howship-Romberg sign).

- Incisional hernia

- As these are usually asymptomatic, patients present with a bulge at the site of a previous incision.

- Lesion may become larger upon standing or with increasing intraabdominal pressure.

Physical: In general, the physical examination should be performed with patients in both the supine and standing positions, with and without the Valsalva maneuver. Examiner should attempt to identify the hernia sac as well as the fascial defect through which it is protruding; this allows proper direction of pressure for reduction of hernia contents. The examiner also should identify evidence of obstruction and strangulation.

- When attempting to identify a hernia, look for a swelling or mass in the area of the fascial defect.

- Place a fingertip into the scrotal sac and advance up into the inguinal canal. If the hernia is elsewhere on the abdomen, attempt to define the borders of the fascial defect.

- If the hernia comes from superolateral to inferomedial and strikes the distal tip of the finger, it most likely is an indirect hernia.

- If the hernia strikes the pad of the finger from deep to superficial, it is more consistent with a direct hernia.

- A bulge felt below the inguinal ligament is consistent with a femoral hernia.

- Strangulated hernias are differentiated from incarcerated hernias by the following:

- Pain out of proportion to examination findings

- Fever or toxic appearance

- Pain that persists after reduction of hernia

Causes: Any condition that increases the pressure in the intraabdominal cavity may contribute to the formation of a hernia, including the following:

- Marked obesity

- Heavy lifting

- Coughing

- Straining at stool or urination

- Ascites

- Peritoneal dialysis

- Ventriculoperitoneal shunt

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Family history of hernias

- Undescended testes

Lab Studies:

- Complete blood count

- Test is nonspecific.

- However, when considering a strangulated hernia, the WBC may be elevated and/or shifted to the left.

- Electrolytes, BUN, creatinine

- For determination of the patient's state of hydration

- Rarely needed except as part of a preoperative workup

- Urinalysis - Obtained to narrow the differential diagnosis by ruling out hematuria or pyuria

Imaging Studies:

- Imaging studies are not required in the normal workup of a hernia.

- Ultrasound can be utilized in differentiating masses in the groin or abdominal wall.

- If an incarcerated or strangulated hernia is suspected, the following imaging studies can be performed:

- Upright chest x-ray to exclude free air

- Flat and upright abdominal films to diagnose a small bowel obstruction

- CT scan or ultrasound may be necessary to diagnose a spigelian hernia.

- Reduction of a hernia

Further Inpatient Care:

- All incarcerated or strangulated hernias demand admission and immediate surgical evaluation.

Deterrence/Prevention:

- Counsel avoidance of activities that increase intraabdominal pressure, such as straining at stool or lifting heavy objects.

Complications:

- If strangulation of the hernia is missed, bowel perforation and peritonitis can occur.

- Hernias can reappear in the same location, even after surgical repair.

Prognosis:

- Prognosis depends on the type and size of hernia as well as on the ability to reduce risk factors associated with the development of hernias.

- Prognosis is good with timely diagnosis and repair.

Patient Education:

- Counsel to avoid those activities that increase intraabdominal pressure, such as straining at defecation and lifting heavy objects.

- Apply support to the hernia.

- Even with asymptomatic hernias, early repair (ie, before it enlarges) is preferred.

For more information onf hernias, check out the following sites:

http://www.hernia.com

http://www.herniasupport.com

Thanks,