How To Instantly Unlock Perfect Pressing Form

Set up, then pause, exhale, and let the weight drag your arms down. Fun? Definitely not. But strength legend Marty Gallagher says it's the key to unlocking the strength you've been seeking. Here's how to embrace the grind for gains!

Ask Marty Gallagher, and he'll tell you the answer has been in front of you all along. You simply weren't willing to let it sink in.

A former world-champion powerlifter, strength coach, and author of two bona fide strength classics, "Ed Coan: The Man, the Myth, the Method" and "The Purposeful Primitive," Gallagher is also like the strength world's version of Henry David Thoreau. He has no patience for all your complication, artifice, and excuses. If you've ever followed one of those programs that has you do just a couple of lifts a day for months on end—and gotten terrifyingly strong at them as a result—you've felt his influence.

Today, he plies his craft with two populations he calls "the outliers: the elite and the afflicted." One day, he'll be working with high-level military operators, the next, a morbidly obese client unable to leave the house. The two can't have anything in common from a training perspective, right? Actually, in both cases, he says, the answer to increased strength and functionality can be summed up in four words: making light weights heavy.

Fresh off the release of his deadlift-able new book, "Strong Medicine: How to Conquer Chronic Disease and Achieve Your Full Genetic Potential," co-authored with Dr. Chris Hardy, Gallagher told Bodybuilding.com about the unique power of a well-timed pause. Before you post your next PR, take his pause-relax-grind test and see how strong you really are.

QYou say that your overriding philosophy is to "make light weights heavy." Why make things so difficult?

What we find is that if we are dealing with guys in particular, usually they are playing to their strengths and ignoring their weaknesses. They've got yes men around them who refuse to tell them what they need to be told, which is, "Forget your strengths. They'll take care of themselves. Let's jump on some weaknesses."

An elite athlete is probably at 99 percent of where he is going to get to in his strength area, but you put him in his weakness area, and he might be at 62 percent. So let's go there. Of course, nobody likes that stuff. But that's what we do: We take them back to ultra-basics.

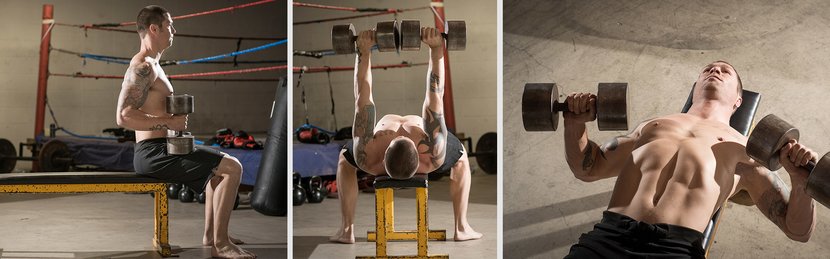

To start, we have them do stretch bench presses with dumbbells. Feel the pec pull off the breast plate, feel the stretch on each rep. You go from complete relaxation to full and complete contraction on every rep, embracing the sticking point and slowly pushing with perfect technique. Make no mistake: It's hard as hell. We're like, "That's right, sissy, a light weight is totally owning you. So let's do something about it."

The Right Way to Bench by Marty Gallagher

- Select two dumbbells and sit on the end of the exercise bench with both dumbbells. The handles should be vertical, with the plates in your lap.

- Lie back and simultaneously turn the handles outward. You are now lying on the bench with the dumbbells in the bench-press start position.

- Exhale and allow the dumbbells to sink. Maintain control. Even though your pecs and shoulders are relaxed, your grip stays tight. The dumbbells are now in push position.

- Relax and feel the dumbbells stretch the pecs and shoulders downward. Perform this "pre-stretch" at the start of every single rep.

- Maximally inhale so that you are full of air at the same instant the dumbbells touch the chest at the bottom of the descent. Then exhale, relax, and stretch.

- After allowing the bells to stretch downward, consciously re-engage the pecs, delts, and triceps. Shift from stretching and relaxation into pushing and contracting.

- When it is time to push, inhale mightily and push upward. The rep speed is not fast or super slow, but it is consciously slowed. This consciously slowed rep speed is called "grind." Grind the dumbbells to a hard (full and complete) lockout. Synchronize your exhalation to end at lockout.

- This unorthodox technique accomplishes two monumental tasks: It ingrains perfect technique and it stimulates the maximum number of muscle fibers.

- This fundamental bench-press technique succeeds in making light weights heavy, staying true to our overall philosophy.

- All subsequent bench-press variations spring from this pause-relax-grind technique. After practicing this technique, all other forms of benching are easy.

Forget regular range of motion—I want exaggerated range of motion. Let's make that our base. From there, we'll build up. Then, when you can do 315 for 5 reps, you've got something.

People go into the gym and think, "I've got to keep moving, keep moving, just do my reps." What magic does a simple pause of a second or two bring?

It's just excruciating! It just adds a degree of difficulty that makes a weight so damned heavy, but you stay in this precise perfect-groove technique. It works the entire musculature, every inch of the range of motion, and you strengthen over that entire range of motion.

I do a lot of work with military guys, and one of the things they love about this system is how it reduces their injuries, because we are strengthening tendons and ligaments. When you think about it, a parallel squat is a half squat. Would you do a half bench press? Would you do a half deadlift? So why are we doing half squats? I don't know. Someone tell me, please. "Oh, you'll blow your knees out." No you won't.

You're a guy who's done a lot of heavy lifting, so put it in perspective for us. How difficult, in barbell terms, is something like a strict goblet squat?

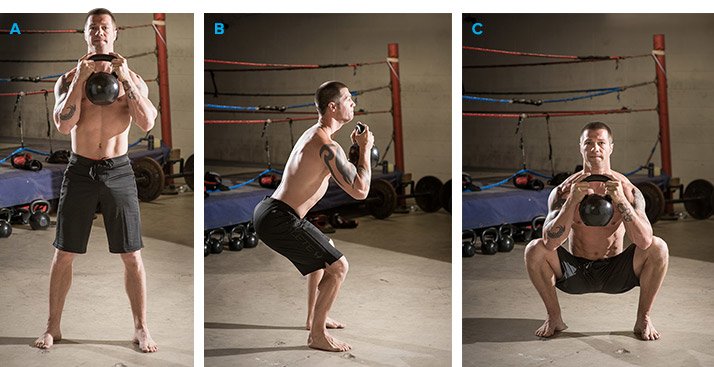

Seventy pounds will give me a battle in a strict goblet squat, and that's a beautiful thing. But the first step in learning how to squat is finding a stance width that allows you to sit all the way down with a vertical torso, and that takes some time and attention. Everybody's different, and more than likely you're not going to be strong where that is.

So that's another ego buster, because we have to find that peculiar and particular stance width that will allow you to squat in a biomechanically correct way. We want vertical shins, vertical torso. Ideally, we want just the femurs to move.

Then, go all the way down, like a Vietnamese rice farmer preparing a net. Inhale on the way down and just sit down there. Pause, keeping your knees spread, and then boom, come all the way up, locking out on every rep. Hold a kettlebell under your chin, and you'll find that 24 kilos (53 pounds) will give a normal man a hard struggle for 5 reps.

We build our squats from the bottom up; everybody else builds there's from the top down. When my guys only have to go down to two inches below parallel in competition, they go, "God, that feels like cheating!"

The Right Way to Squat by Marty Gallagher

- Hold a single appropriately-sized kettlebell or dumbbell at chest height with both hands.

- Start with a shoulder-width stance, toes turned slightly outward.

- Sit back and down while keeping your knees vertical. Do not let your knees shoot forward.

- Keep your weight balanced midfoot; do not shift forward or backward.

- Inhale into your lower belly as you descend.

- Force your knees out to the sides (laterally) during descent and ascent.

- Your knees should stay over your ankles as much as possible; they should not shoot out in front of the toes.

- Sink all the way to the bottom, or as far as you can descend while maintaining correct form.

- Exhale in the bottom position, then relax and sink further, losing all tension. (Only perform this step with bodyweight or light loads.)

- After a one-second pause, using diaphragmatic breathing, inhale to ascend while pushing your gut out against your thighs. For heavier loads, use this alternate technique: Inhale, then sink to the bottom while maintaining tension. Pause for one second. Exhale at the top of the ascent.

- When ascending, do not let the tailbone shoot up first. The tailbone and upper body should move as one unit during ascent. "Grind" out of the bottom position.

- Follow the sets and reps of your current program. Stop immediately if your technique breaks down.

What about the non-elite person who is used to sitting but not squatting? How transformational is learning to squat for that person?

Leg power is everything. Leg power is the key to human power. Leg, back, and then front torso—in that order.

One way we teach people to squat is by putting them next to a pole, and we have them squat down and take the weight off until they can sit in that bottom position. They're pulling up on the pole, so they're able to just sort of relax down there, because their full weight is not impacting them.

I'll have them cling to a pole and perform forced reps. Anything to keep them from breaking form. It is better to fail with technical integrity than to succeed with corrupt technique. I'd rather say, "If you're only good for three, that's good—cut it off there." We're not going to cheat to get to four and five. That's where the injuries occur and where you engrain improper techniques, so we just cut it off but we allow them to give themselves self-administered forced reps.

They can help themselves up—what's wrong with that? Nothing. They are reducing the payload of their torso, which enables them to squat correctly. Over time, they will use less and less arm pressure until they are handling their own weight for the sets and reps. We like to have our people work up to like 3 sets of 10 with no weight, and then at that point we'll hand them a light kettlebell.

You take a similar approach to the sumo deadlift, which you call the "reverse squat." What do you mean by that?

Think about it: You're over the top of a barbell or kettlebell. You don't bend over—you squat down to it. When your hands feel the handle, you just reverse gears, squat erect, then squat back down. We teach never to let the weight settle or drop. We want it to just touch and then you go. Everybody wants to settle and reset and then come up. No, no, no. We want a slow descent, a light-as-possible touch. We call them "slow-release deadlifts."

So no dropping weights, then.

No, we don't do that. I was taught that by my mentor, powerlifting world champion Hugh Cassidy. We trained in Cassidy's basement, and you'd better not drop the damned weight in Cassidy's basement or you might get kicked out, because they lived upstairs. So we learned all about slow release.

But you know what? It's a wonderful thing, the negative of a deadlift, when it comes to building power, strength, and position. Why throw away the negative? That's crazy. We love the negative. We accentuate the negative.

That's a good sales pitch: "We accentuate the negative."

Yes, we do. The Chinese call it "the negative way." You negate and negate until only the truth is left.