I've been hearing a lot lately from people "in the know" about how competitive athletes should never lift heavy. "All it'll do is make you bulky and slow," they say. "You need high reps. Don't ever squat/deadlift/clean/snatch/row, because those are bad for your knees/back/whatever." You get the picture.

So what's the alternative? I look around, and damnit if coaches don't have their clients standing on a stability gadget with legs akimbo and a kettlebell dangling somewhere or other. For crying out loud, they do stuff that would make my yoga friends cringe! And they call it "functional training for sports." What is that? When has training for sports ever not been "functional?" Can somebody tell me the last time they saw a football field or an MMA cage made up of Bosu balls?

It's time to set things straight. There is a time and place for non-heavy training, for sure. But forsaking heavy training altogether is a bad idea. I've got more than two decades of training elite athletes under my belt from over 30 different sports, and at some point, they all trained heavy. If you want to be elite, I'm here to tell you that, sooner or later, you've gotta put a heavy bar on your back.

Forget What You've Been Told

Before we get into any of the nitty gritty, let's destroy the most prevalent myths I hear from athletes about lifting heavy.

- Lifting heavy will make me fat. Only if you eat more than you need. So don't.

- Lifting heavy will ruin my flexibility. Two words: Flex Wheeler. Next.

- Lifting heavy will make me overtrain. Not if you cycle like I'm going to show you. If you do any type of training too much, you can overtrain.

- I will develop an imbalanced physique if I take out isolation exercises. Way wrong. Compound and multi-joint movements will work every muscle like you never have before. If anything, you're more likely to get "unbalanced," whatever you think that means, by living on a steady diet of isolation movements.

None of this is to say that you should lift heavy all the time, like hitting max lifts five times per week for six weeks straight. Nor is this an excuse to throw around ego-inflating amounts of weight with crappy form. Unfortunately, these are some of the things many people do when they think they're training heavy. Lifting heavy is a planned assault, and I've got your plan.

Why Train Heavy?

In short, resistance training enhances all other types of training. It's simple physics: Whether you want to hit harder, move faster, or hit an extra gear when victory is on the line, you need your muscles to be able apply more force than your opponent's. And your muscles get better at applying that force when you train with heavy weight.

When you train heavy—and correctly—these are some of the benefits you can expect:

- More power for hitting or pushing into balls, the ground, obstacles, or opponents

- More explosive speed

- Long-duration power production from more efficient motor unit recruitment

- Denser muscles

- Bigger muscles

- Increased testosterone production

- Denser bones

- More resilient muscle fibers

How does this sound so far?

Plus, no matter how exciting your sport may be, trust me when I say there's a special type of thrill that comes from walking up to a weight that should kill you, and then moving it against all that gravity. Knowing that you beat the iron, yourself, and your previous PR, even though you're physically drained, delivers an unequaled rush.

The Wavy Road to Heavy

I'm a proponent of what's called undulating periodization, or non-linear periodization. Simply put, it's a training regimen that succeeds by having you alternate very light days with I'm-gonna-crush-myself-to-death heavy days. There have been some people over the last few years who claimed to have invented it, but it's been around for about 60 years and originally came from the Eastern Bloc countries.

Like other forms of periodization, undulating periodization's ultimate aim is to get you to lift a heavier weight over time. But alternating workouts allows you to actually train more than you would be able to if you simply pushed for absolute strength in a linear progression. Along the way, you develop other athletic traits while also saving yourself from injury—and insanity.

Generally, I suggest hitting a one-rep max on a particular lift only about once a month. Now, don't take that to mean you have license to slack off the other three weeks. During that time, you'll be training for speed, power, and hitting maxes on your other lifts. Yeah, not much rest here.

Still, I strongly recommend that a program like this should only be undertaken by an experienced lifter, and if you're a competitive athlete, during an off-season. It can be pretty intense, and I don't want you to overdo it.

The easiest thing for most people to do when implementing a heavy training program, no matter their sport or goal, is to organize their program around three weekly training sessions: a push day, a pull day, and a leg day. Each of these days will also further break down into a weekly heavy strength day, a medium power day, and a light speed day.

Here's an outline of how it would work over the course of a three-week microcycle:

Week 1

Monday: Heavy Legs

>95% 1RM, 3 sets of 4 or fewer reps, 5 minute rest

Example movement: Back squat

Wednesday: Light Push

70-75% 1RM, 4 sets of 10-12 reps, 1 min rest

Example movement: Medicine ball chest throw

Friday: Medium Pull

83-88% 1RM, 3 sets of 6-8 reps, 2 min rest

Example movement: Pull-ups, weighted if necessary

Week 2

Monday: Medium Legs

83-88% 1RM, 3 sets of 6-8 reps, 2 min rest

Example movement: Front squat

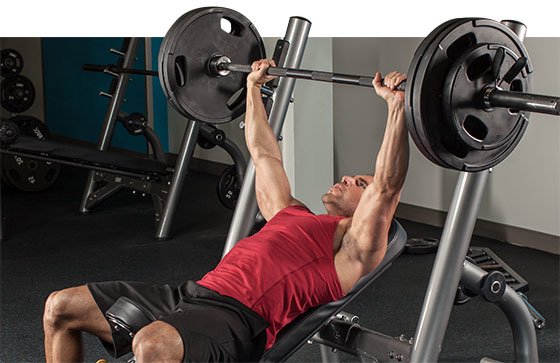

Wednesday: Heavy Push

>95% 1RM, 3 sets of 4 or fewer reps, 5 minute rest

Example movement: Bench press

Friday: Light Pull

70-75% 1RM, 4 sets of 10-12 reps, 1 min rest

Example movement: Speed deadlifts

Week 3

Monday: Light legs

70-75% 1RM, 4 sets of 10-12 reps, 1 min rest

Example movement: Plyometric box work

Wednesday: Medium push

83-88% 1RM, 3 sets of 6-8 reps, 2 min rest

Example movement: Incline bench presss

Friday: Heavy pull

>95% 1RM, 3 sets of 4 or fewer reps, 5 minute rest

Example movement: Barbell deadlift

The Details

Now, after all of this is said and done, you may be asking yourself, "But wait! What about my beloved accessory movements?" You can include them judiciously in this program, but you need to alter your way of thinking about them.

Accessories in this regimen are not the same as in a bodybuilding program. As I mentioned before, we're not really concerned here about isolating any single muscle; rather, our thinking must stay focused on the development of overall strength and improved neurological connection to the muscle group. So accessory lifts should be planned to that end: placed after your primary movements, with similar reps, sets, rest, and loads to the rest of the program. A couple of examples include walking lunges on leg day and floor triceps presses on pressing day. Just don't go so overboard with them that they interfere with the project of building strength!

Another question that rarely gets asked but usually should: "What if I miss a day? Is the whole cycle ruined?" The great thing about this program is that it is flexible and can be altered depending on the condition of the athlete on a particular day. For example, say we're doing a 6-week cycle, and we have an athlete scheduled for a heavy leg day, but he comes into our facility feeling exhausted from practice. Max effort is out of the question, so we can switch out his heavy leg day for a light leg day, and then we'll make up the heavy day the next week. As long as the integrity of the overall program is maintained, he'll keep making progress.

This program is simple, but I've seen it work wonders with a wide range of athletes. Cycle it in and benefit from the basics. Strong muscles are the foundation of everything else in athletics, so don't be afraid to go heavy!