The kids on our high school hockey team were mostly big, and always tough. When they got into street fights outside Burger King, they pulled their opponent's T-shirts over their heads to restrict them—an old ice hockey trick— then beat them with meaty, practiced fists.

The football players were tough, too. During after-school practices, they did "up-downs" like grunting bulls humping the manicured grass. At lunchtime, they double-fisted sandwiches and pushed people against lockers.

The wrestlers were also tough, to say the least, but they rarely had to fight in the streets or hallways to prove anything. When they walked, their lats opened up like paper fans. Obviously, the bigger the wrestler, the wider the berth given to him.

I was on the wrestling team for a year but, as a natural 98-pounder, I had no lats. My version of cutting weight was skipping candy on the way to a match. My nickname was "Mighty Mouse," but I wasn't super mighty. The coach called me that as a joke, I guess.

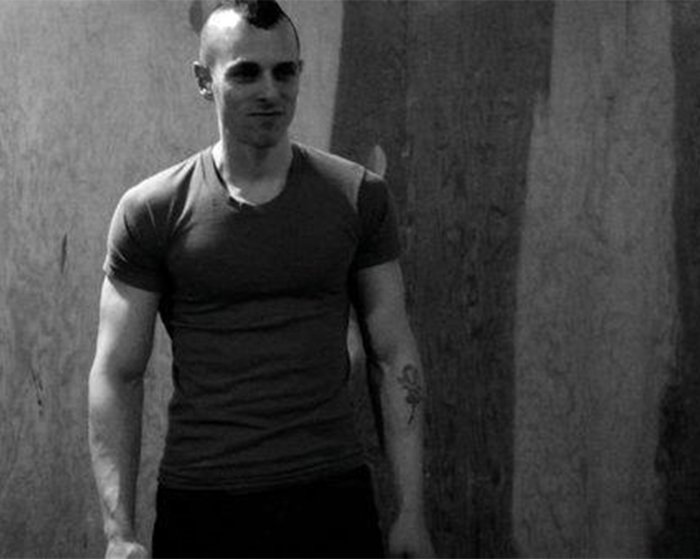

In contrast, Robert Young was mighty—I'd heard he'd learned to box at the Kronk Gym in Detroit, where Thomas "The Hitman" Hearns had come up. And Ricky Smith was mighty, I thought. He had a 12-inch-tall mohawk, was big-boned, and had a thick neck that was sometimes wrapped in a spiked dog collar to match his leather wristbands and combat boots. Nobody ever messed with either of those guys.

Comparatively, I felt like prey—and that pissed me off. I was in the tenth grade and weighed less than the Everlast heavy bags other kids practiced combinations on. And, because I felt like prey, I behaved as prey. I took shit from anybody who gave it to me—and so it kept coming, and I stayed awake in fear at night, dreading the coming day.

At 16, I did three things that changed my life: I got good with a throwing star, I learned to use words as weapons, and I started lifting weights.

Throwing Stars, Pressing Points

My accuracy with a throwing star was an indicator that there could be a physicality transcending brute strength. Hand-eye coordination, speed, and some degree of mind control were the skill sets honed. My instinct told me that these would outlive some jackass' ability to shoulder-check me into a drinking fountain.

The second thing that gave me an edge was learning to crystalize my thoughts into speech. Instead of fearing the approach of bullies, I stepped into them, my words cutting like an open-hand fighting technique, finding my potential tormenter's pressure points. A properly spoken counterattack, I found, could derail and defeat most oncoming threats. This remains true.

Still, until I learned to lift weights, I felt incomplete. Intellect and sleight of hand were the most valuable, least expensive tools to sharpen, but lean muscle mass was accompanied by respect.

"Damn"

I started lifting weights at a traditional heath club, where my stepfather played tennis on the weekends and old people sat naked on white towels in the sauna.

Six months into my first year of weight training, I went to the lake with my friends and, when I took off my shirt, my abs were like rippled sunlight on the water. My chest and arms were fuller and rounded. My girlfriend said, "Damn."

For 30 years, I've remembered that word rolling off my high school girlfriend's tongue. "Damn" meant strength. "Damn" meant a future beyond the contrived natural selection of high school. "Damn" was a word that released the fear.

And "damn" is what's carried me through three decades of weight rooms since, as I've recovered, every few years, from bouts of crippling depression, or temporary financial ruin, or just the heaviness of a world gone rogue from my expectations of it. In the gym, I carved away at the excess malaise, the sculpting of abs an indicator of the strength of my personal core.

When I am weakened inside by turmoil, that weakness is displayed on the outside. When I return to the gym, I am returning to interior health. My abs are a mere trophy. They are meaningless without the considerable struggle to find them.

If the gym is a sanctuary, "damn" becomes prayer, remembered and repeated.

Eat, Pray, Lift

In college, I lifted with friends in the basement of our dorm. The weight room was tiny and musty, outfitted with a portable radio and a few vertical mirrors that looked like they'd been ripped from the walls of a Sears dressing room. I made costly mistakes during those years, like foolishly attempting to military press more than my body had learned to accept. I felt something pop in my upper back, then wore a neck brace for two days afterward.

What I remember most is not the pain, but how the pain hobbled me. I could pray for gains, eat 4,500 calories a day in the dorm cafeteria, and the end result was the same. In college, I learned that I would never outsmart the mechanics of the body.

After college, I spent a few years traveling the country, hitchhiking or taking Greyhounds or driving cars that broke down halfway to wherever, and relying on gyms, at every pin on the map, to save me from loneliness, or heartache, or whatever I suffered from those days.

I remember thumbing into Colorado, depressed and with only $30 to my name, not knowing what my life would have in store for me. I felt godless and empty inside. I spent $6, a fifth of my entire net worth, on a day pass to a gym so that I could lie back on a bench, wrap my hands around a barbell with a 45 on each side—that's all it took—and remember that I was alive.

There was something greater than myself inside. That is what I was honing. The reps were a chant, a prayer. Those gyms across the country were where I worshipped, to stay on track spiritually, although my road was haphazard.

When I became a father, my sense of self was continually tested, so when my kids were old enough to drop in the daycare at our local YMCA, I greedily stole those hours to practice Olympic lifts and do pull-ups. On Saturdays, the gym was filthy. On Sundays, it was freezing cold. From 5 p.m. to 7 p.m. during weekdays, the place was a zoo. But, if the daycare was open, I wouldn't miss a workout.

After 60 minutes of lifts, I always knew who I was again.

Maximum Weight

At 32, I decided to "get huge" for the first time in my life. I started taking creatine and a variety of pre- and post-workout supplements. One night, I thought my appendix had burst, so I drove myself to the hospital. On the way, I pulled over twice, my arms wrapped around my stomach like I'd been gut shot. In the ER, a nurse stuck an IV in my arm and hydrated me. Within minutes, I felt fine.

Rule number one, I learned: No matter what you're taking, don't forget to drink water, too. The $1,100 ER bill was an expensive lesson, one that ruined my credit for a couple of years and had almost killed me to learn.

Another thing I learned soon after was that my body seemed to have a maximum weight it was comfortable with, just shy of 150 pounds. I worked out an hour a day, took creatine and protein shakes, ate regularly, got stronger, and looked great, but that number wasn't budging.

I often sought advice from friends I'd made at my gym. They'd tell me things like: "Never let yourself get hungry. Eat a hamburger every night before bed. Drink a gallon of milk a day."

I'd think to myself, "You people are gross." After all, I felt good—I mean, really good. When I tried to eat beyond my comfort level, I felt like shit.

I realized that, in order to move up in weight classes, I'd have to turn an "effort" into a "lifestyle." I wasn't sure if I was ready to do that when every forward motion was met by nausea, stomach aches, sluggishness, and heartburn.

I still admired the strong and the large, but it dawned on me that I was no longer prey to them. I could move quickly and still had enough muscle strung along my bones to have power behind a fist fight. Sure, it was a primitive measure of my worth in a civilized society, but still relevant in the animal kingdom of my insecurities.

If I were agile, mentally sound, and physically capable, what more could I want? I decided that I was fine, briefly.

Saying Nothing

By 35, I was an English professor at a decent university. Many of my students were athletes, some who went on to play professionally. I loved teaching athletes how to craft their writing, and I think they enjoyed me teaching them.

I would say things like, "Don't think of your homework as a five-paragraph essay, think of it as a leg day with five exercises. Each paragraph is an exercise made up of 3-4 sets, or sentences. Each set or sentence is made up of a max of 15-20 words, or reps."

Pretty soon, my athletes learned that if they could bang out 3-4 sets, they had themselves a paragraph. Warm-up, squats, deadlift, leg press, cool-down—they had themselves an essay.

One day in class, I was sitting next to a student athlete who, later, played professional football. Our legs were side by side. His, like filing cabinets; mine, like longneck bottles of beer, in comparison. He was so large that I found myself imagining fighting him, picturing him destroying me, remembering the powerlessness I'd felt as a boy, still poignant all those years later.

When I went home that night, I remembered how four kids in high school had taken the hat off a boy with cancer. They played "keep away" while I, a freshman, walked by and said nothing.

The Body is Like a Jenga Stack

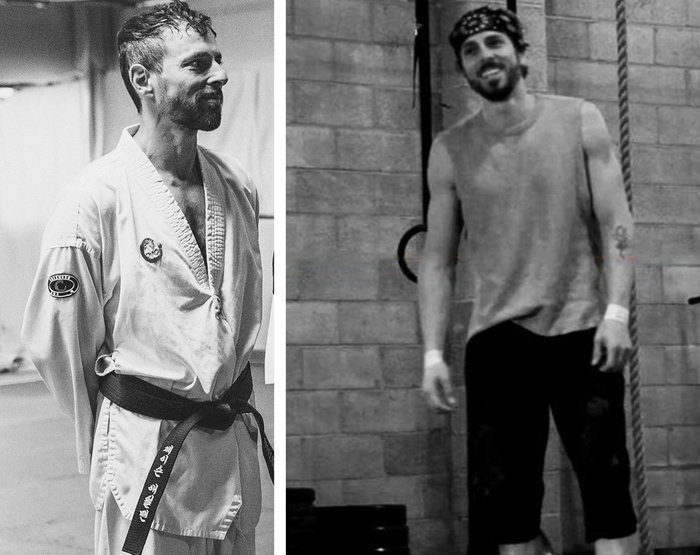

In my late 30s, I began taking taekwondo lessons. In a few years' time, I was decent. I could high kick the threshold to my bedroom door or throw a bone-breaking roundhouse to the ribs or face of an opponent.

My goal was to become a black belt because, at 15, I had been sucker punched and hadn't fought back, an internalized point of contention, like the kid with cancer, that began to nag at me as I approached 40. I would tell myself, "We are supposed to say something. We are supposed to fight back."

To assist with my endurance training, I joined a CrossFit box, where I discovered that I could do more pull-ups than anybody else. Strong athletes kipped through high-rep sets but I blew them away, and usually didn't even kip. At some point, I did 40 strict pull-ups in 60 seconds.

That number seemed high, so I got online and discovered that I was only 7 reps shy of the world record. I started training to beat that record, for no other reason than to say I had beat it. I started doing pull-ups nonstop, in all variations: weighted, jumping, clapping, and superset with muscle-ups and rope climbs.

Shortly afterward, one of my lats became stressed.

When doing clean and jerks the next week, I overcompensated with my strong side, protecting the injured lat. Then, a shoulder became stressed, due to the imbalance.

During thrusters the week after, I overcompensated with my stronger shoulder, injuring my back. Because my back was tweaked, I became guarded in my deadlift. The imbalanced deadlift form led to even greater pain.

Everything started breaking down.

My body felt like a Jenga stack, with structurally-important pieces, turn by turn, being taken away. Instead of 40 pull-ups, I could now only do 30, and then 25. And the world record went up to what was now over twice my newer, lesser capability.

My martial arts practice turned to shit. I'd kick a practice bag, and a current of pain would shoot from my foot to my glute, make a right turn at my lower spine, and travel up to my neck.

I had to take a year off from training, and I had to learn to move slower when I went back.There were no more rope climbs, no more deadlifts for a while. When I kicked a bag, I didn't kick as hard.

The hubris that led me to attack a world record had become the humility of failing, and it was justified. I had trained impulsively. I had prayed for a win, but received a lesson.

The Hard Gain

Now, I am near 50. At 3 a.m. some nights, I'll awaken because leaves are rustling outside my home, or because my internal clock fears that time is running out.

In the bathroom mirror, I see wrinkles around my eyes, and grey hairs. My body, however, is more or less the same as it was at 25. My kids are now close to the age that I was then.

Today at work, a woman dropped a 10-pound bag of protein powder on my desk and told me, "You should take this home and drink it." I sometimes still complain about my weight, so she's only being nice.

But haven't I done enough to prove myself capable, regardless of body weight? I have shoulder pain and still weigh 150 pounds, but I can train regularly and I can still see my abs. I'm still capable of doing the work I love on the interior, and seeing it on the exterior.

Shouldn't I, then, at the end of the day, have nothing left to prove to myself, or to those early childhood memories of fear and inaction? There are skill sets that last longer than biceps, and didn't I master them, and even get those biceps along the way?

So what if I never surpassed welterweight status? This thing called life is a long game, I tell myself.

And yet, I still reflect on the hallways that I couldn't walk down, and the sucker punch to my eye that kept it closed for a week, and the much darker things that I didn't talk about here.

We may walk with prayer, but we are burdened by self. When I look in the mirror, this is what I see sometimes: That person stepping toward me, whom I'd better step to first, with hands or words or whatever cuts quickest.

Gaining weight is hard for a lot of us. It's not as easy as milk and meat.

But ask many hardgainers, and this is what they'll tell you: The real hard gain is in moving ahead, from whatever it was that first put us here.