Sometimes, I miss the days when Wikipedia was still in its infancy. Back then, there was a decent chance that you'd click over to see when Lincoln was assassinated, and find out it was during the finals of the 1978 World's Strongest Man competition. Or you'd discover, to your great surprise, that you once had a short but intense feud with the rap group NWA.

Point being, not that long ago, everything on the Internet came with a healthy dose of skepticism attached. Today, there's so much kinda-sorta OK, more-or-less convincing information out there—especially when it comes to health and fitness—that you're more likely to be led astray than ever. What's a lifter to do?

The answer: Become a scientist. And if you can't, try to find a way to keep abreast of people who can. This is what drove Bret Contreras and I to launch Strength and Conditioning Research, a journal we hope can help athletes and trainers all over the world stay afloat in the ocean of new data. Each month, we recap dozens of new studies in the fields of strength and conditioning, hypertrophy, biomechanics, and nutrition.

In this month's installment of Research Roundup, I'll summarize three important recent studies recapped in our journal and explain what they mean for you. See the definitive answer to the question of whether beginners should perform isolation exercises, find out whether inter-set stretching actually works, and discover whether higher protein intake increases the retention of lean body mass during weight loss.

1 / Pound-For-Pound, Compound Can't Be Beat

Resistance exercises fall into two categories: compound and isolation movements. Compound movements generally involve a prime mover or movers and some accessory muscles. Examples include bench press, pull-up, squat, and deadlift variations. Isolation exercises involve one muscle or muscle group—for example, biceps curls, triceps kickbacks, and leg extensions.

Some researchers and coaches have suggested that muscular development can be optimized in beginners without the use of isolation exercises. Others suggest that even beginners should make use of isolation exercises from the outset in order to achieve optimal development of all muscles.

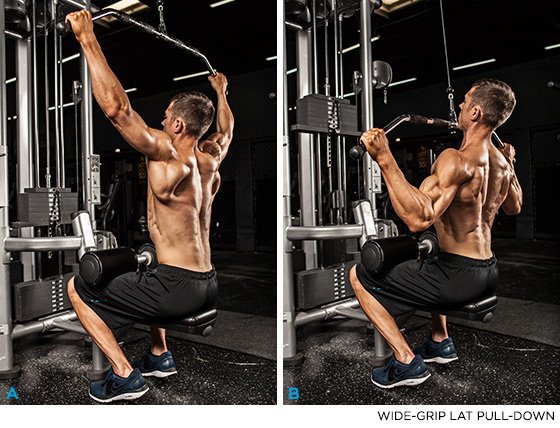

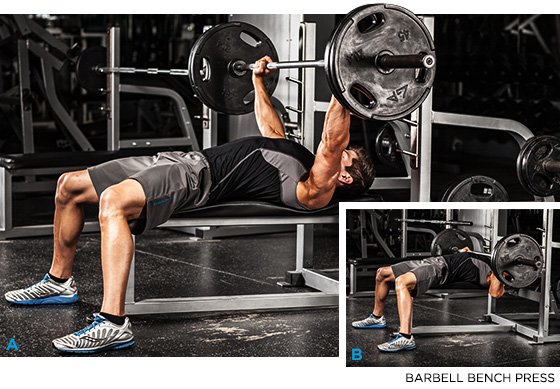

The researchers wanted to determine whether single-joint exercises contributed to the gains achieved in upper body muscle strength and size in young, untrained males. The researchers recruited 29 subjects, who were divided into two groups before participating in a 10-week training program. One group performed only compound exercises—the bench press and lat-pull-down—while the other group performed these exercises as well as two isolation exercises, the triceps extension and elbow flexion exercises. The exercises were performed 2 days per week for 3 sets of 8-12 reps to failure.

After 10 weeks, the researchers reported that both groups increased muscular size of the upper arm musculature by 6.5 to 7 percent, and muscular strength of the elbow flexors by 10.4 to 12.9 percent. There was no significant difference in the gains in size and strength achieved between the two groups. The researchers concluded that the stimuli provided by compound exercises are sufficient to promote optimal gains in both muscular size and strength in untrained subjects training under this manner of program.

The study was only performed over a 10-week period, and different results might be observed over a longer intervention. Also, the study was performed using untrained subjects, whereas different findings might be made in subjects who have a history of resistance training.

Moreover, the study was only performed in relation to upper body muscles. A different result might be observed in a study of the lower body musculature. Finally, the programs were not volume-matched, so different results might have been obtained if the multi-joint program's volume had been increased to mirror the combined multi-joint and single-joint program.

All of that aside, this study seems to support the view that in general, beginners should concentrate on progressing in compound movements. Isolation exercises can be saved until they have achieved a basic grounding in resistance training.

2 / Rest Period? You Mean Stretch Period

Stretching has been found to help increase joint range of motion, which can help immobile athletes perform certain exercises they would otherwise not be able to manage. However, a number of recent studies have cast doubt on the benefits of stretching during training. One study found that stretching reduces explosive power among athletes in subsequent exercise. Recently, another study found that inter-set stretching also reduces performance in subsequent bench press sets. However, long-term stretching programs seem to have a small hypertrophic effect. When these studies are taken as a whole, the question remains inconclusively answered: Does inter-set stretching help or hinder strength and size gains?

The researchers wanted to compare the effects of 8 weeks of strength training with and without inter-set static stretching. They recruited 16 males who had at least 2 years of resistance training experience and divided them into two groups. One group performed the program with inter-set static stretching and the other performed the 8-week strength training intervention without.

The strength training intervention involved the machine bench press, leg extension, low row, leg curl, shoulder press, and leg press. Each exercise was performed for 4 sets of 8RM with a 2-minute inter-set rest interval during which the stretching group performed relevant static stretches of the muscle involved for 30 seconds while the control group rested. Between each exercise, the rest period was 5 minutes. Training loads were adjusted upward as the subjects increased in strength.

Over the course of the program, the researchers noted significant increases in strength in the leg extension and low row for both groups. There was no significant difference between the two groups' respective increase, although there was a non-significant trend for the stretching group to display a slightly greater increase in strength in these exercises. The researchers concluded that inter-set stretching does not impair strength gains.

The study was limited to an analysis of strength gains and did not address changes in muscular size, which would have been valuable. Also, the study was performed in moderately trained males, while different results might be observed in either beginners or more advanced subjects. Additionally, the length of the stretch was moderate, at 30 seconds, and further studies might benefit from investigating longer stretches of around 45-60 seconds.

However, based on this study, it seems that some inter-set stretching does not hinder strength gains in intermediate lifters. In fact, it might be beneficial.

3 / Lose Weight, Keep It Off With Protein

A few of the most beneficial conditions for weight loss include a caloric deficit, maintaining feelings of satiety, and sparing lean body mass. It is thought that energy-restricted diets with relatively high protein content, as compared to current dietary guidelines, are beneficial in this respect. However, as anyone who has ever lost weight and gained it back can attest, a dietary schema that doesn't translate to weight maintenance afterward is of little use. So where does protein intake fit into that challenge?

The researchers wanted to investigate the effects of dietary protein content on weight loss, bodyweight maintenance thereafter, and body composition during a 6-month restricted energy diet undertaken by 80 overweight and obese subjects. They decided to examine absolute protein levels at two levels: that of the current dietary guidelines, which is 0.8 g per kg of bodyweight per day, and at a higher level of 1.2 g per kg of bodyweight per day. The caloric intake during the 6-month period was structured in three phases: 2 weeks of 100 percent of maintenance energy requirements, a 6-week weight-loss phase at 33 percent of original maintenance energy requirements, and a 17-week maintenance phase at 67 percent of original maintenance energy requirements.

The researchers reported that bodyweight, BMI, and waist-to-hip circumference ratio reduced in both higher and lower protein groups, and that there were no significant differences between groups. The higher protein diet group lost 5 kg in the 6-week weight loss phase, while the lower protein group lost 5.9 kg. In the 17-week maintenance phase, the higher protein group lost another 2 kg, while the lower protein group lost 1.3 kg.

The researchers also reported that fat-free mass reduced significantly in both groups. However, the lower protein group lost more fat-free mass than the higher protein group. The lower protein group lost 1.3 kg of fat free mass in the 6-week weight loss phase and put 0.5 kg back on during the 17-week maintenance phase. However, the higher protein group lost just 0.6 kg of fat-free mass during the 6-week weight loss phase and also gained back 0.5 kg on during the 17-week maintenance phase.

The researchers concluded that inadequate protein content in the diet greatly contributes to the risk of bodyweight regain. They concluded that a higher protein diet of 1.2 g per kg of bodyweight preserves more fat-free mass than a diet of 0.8 g per kg of bodyweight.

While promising, this study raises several questions. First and foremost, the population used was overweight and obese, whereas different results might be observed in other populations. It is also not known whether higher amounts of protein than 1.2 g per kg of bodyweight per day would lead to greater retention of fat-free mass. Moreover, it is unknown whether combining resistance training or other exercise in this population during the weight loss period would have resulted in greater retentions of fat-free mass in combination, either with or irrespective of protein intake.

Notwithstanding the above, the study implies that higher protein intake than the recommended daily intake could lead to better retention of lean body mass during periods of dieting.