Why I Choose Olympic Weighlifting Exercises...

Many of the lifts I'll mention are taken from Olympic weightlifting, which has lost mainstream popularity since the early 1970s when powerlifting became the preeminent strength sport in the United States. Despite Olympic lifting's lack of popularity, there are still a number of Olympic lifts that are definitely helpful to the powerlifter, bodybuilder or any other strength athlete.

Some of these lifts will help build explosive power, which is a benefit to field event athletes, football players, rugby players and those interested in simply increasing explosiveness. I'll also make mention of an "old-timer" lift used by turn of the century strongmen like Arthur Saxon, Louis Cyr and Hermann Goerner. What these men lacked in overall muscularity was offset by their total body strength and ability to support massive amounts of weight in events requiring pure isometric strength and strength endurance.

Some of these lifts will help build explosive power, which is a benefit to field event athletes, football players, rugby players and those interested in simply increasing explosiveness. I'll also make mention of an "old-timer" lift used by turn of the century strongmen like Arthur Saxon, Louis Cyr and Hermann Goerner. What these men lacked in overall muscularity was offset by their total body strength and ability to support massive amounts of weight in events requiring pure isometric strength and strength endurance.

As a whole, Olympic weightlifters are undoubtedly the most explosive athletes on the planet. Their ability to accelerate a heavy bar with rapid speed is staggering. Imagine the combination of brute and explosive strength needed to move a 260 kilo barbell from the floor to an overhead position! Many of us have the visual impression of the +105kg lifters, who tend to be a bit portly, so we often overlook the ability of the Olympic lifts to build solid muscle mass.

However, if you have seen Olympic weightlifters in the 105kg and lower weight classes, you'll see lean, muscular bodies capable of moving massive amounts of iron with blinding speed. I'll expand a bit on the individual lifts to give an idea of what each entails. When you say "clean and jerk," most people are pretty familiar with what that means. If you mention a "power-snatch," you'll possibly get a puzzled look from most guys (or ladies) in the gym, or possibly even a leer from someone with a dirty mind. Ideally, once you read this article, you'll have a solid understanding of what some of these lifts are and how they can help you reach your training goals. Now, let's have a look at some of the lifts.

The Jerk & It's Variations...

In Olympic weightlifting, the jerk is the movement that completes the clean and jerk sequence in competition. The lifter cleans the weight from the floor while dropping into a position that very closely resembles the bottom portion of a front squat. This initial phase is called a squat clean, which means that the clean is completed with the lifter dropping into a very low bottom position to rack the bar.

In a power clean, the lifter will only dip a bit with the knees to rack the bar on the clavicles. The weights used in competition require a full squat position in order to give the lifter time to drop under the weight and solidly rack the bar. When the lifter rises from the bottom position, it's time to drive the bar overhead and lock it out completely if he is to be granted a successful lift.

Generally, with a very heavy weight, the lifter will perform a split jerk to get the bar overhead. A split jerk begins with the lifter bending the knees and using hip, back and leg strength to blast the bar upward. At the same time the bar is rising, the lifter will shoot one leg forward and one rearward, hence the term "split." This is a double knee bend, because the knees are bent once to initially drive the bar overhead and then a second time to get under the bar to receive it in a fully locked out position. The bar is racked overhead while still in the split position, at which point the lifter will bring the feet back together to exhibit full control over the bar.

There is obviously a great deal of timing needed to drive the bar up and split the feet while dropping under the bar and catching it in a locked position overhead. This action also requires a great deal of leg, back, shoulder and hip strength to drive the bar from the shoulders with sufficient speed to get under it. A great military press definitely doesn't mean that a lifter will have a great jerk, although strong shoulder pressing ability certainly helps.

In contrast to the split jerk, the power jerk is performed without the feet actually moving. The lifter bends at the knees and begins driving the bar overhead in the same manner as in the split jerk, but only bends the knee again to get under the bar for the lockout. The feet may come off the floor a bit, but they do not move except maybe outward just a bit (laterally rather than forward/backward). Again, there is a double knee bend, as in the split jerk, but the feet stay in basically the same spot and the depth is approximately that of a � squat.

This technique is seldom seen in competition, but used very frequently in training sessions by Olympic lifters. Since the lifter is unable to get as low (by not splitting the feet) during a power jerk, it requires a stronger drive off the shoulders (and use of less weight). For these reasons, lifters will use the power jerk to work the initial drive off the shoulders. It's hard to actually see the movements on video because of the speed used in executing the lifts, but if you can watch Olympians training in slow motion, you'll see each corresponding step for the aforementioned lifts.

As for training the jerk (either variation), I'm personally fond of doing nothing more than doubles. Generally, a lifter may clean the first rep, perform the jerk, then replace the bar into a squat stand or power rack. This is purely to preserve energy for the clean, thereby allowing more sets or repetitions without generating as much fatigue. Just take the bar off the rack, do a jerk (or two) and replace it.

Rest, repeat. It's very easy to let the bar travel backward when learning the jerk. Many Olympians lose the lift behind them; so don't worry if it takes a bit to learn the positions for locking out the lift. The biggest factor with the jerk is driving it straight up from the shoulders; don't let it move forward or backward if possible. Your body positioning when you get under the bar will allow you to receive the bar directly over your head. Your arms should be straight at this point and perpendicular to the floor.

If they're out of line, the weight will either pull you forward or backward and you'll lose the lift. I'd also strongly suggest using bumper plates if you have access to them, for any Olympic lifts. You'll notice that the bar is basically "dropped" from the overhead position when Olympic lifters complete the lift. They're using bumpers and dropping the bar onto a lifting platform with rubber mats, so no damage to either the surface or the plates will happen.

Bumper Plates are very expensive, but a good set will last a lifetime. I've seen some lifters place some sandbags or old tires on the floor to allow steel plates to be dropped without damage. If there is sufficient interest, I can write a small piece on building a simple Olympic lifting platform at a very low cost.

Push Press *

* (From front or behind neck)

Another lift rarely seen today is the push press. It fell from popularity after 1972, when the military press was removed from official Olympic weightlifting competition. For building pure shoulder pressing strength, the push press is supreme. The overload allowed by the lift gives the deltoids and triceps a tremendous stimulus when compared to the jerk variations, which rely more heavily on momentum imparted on the initial drive from the shoulders.

The push press begins in a manner similar to the jerk, except the knees only bend once. This means that the lifter will dip at the knees and use a strong drive with the hips and legs to impart initial momentum, then the bar is pressed overhead as the lifter returns to a standing position. Since there is no "second knee bend/dip" to allow the lifter to get "under the bar," the lift requires an actual press-through to completion.

The initial dip is just to get the bar moving from the bottom, after which the shoulders and triceps take over and provide the force needed to complete the lift. An analogy would be a something like a cheat curl. You get the bar moving with a little swing at the bottom, then rely on arm power to complete the curl. The push press should allow you to use a great deal more weight than used in a standard military press, where no momentum is used.

By performing the push press regularly, you'll be able to help build pressing strength from the mid-point of the lift through lockout. Further, the initial momentum allows much more weight to be used, so the shoulders and triceps get a heavier overload than that given by the military press. Push presses can be done with the bar starting in front of the neck or behind the neck. This is purely a matter of personal preference.

Overhead Squat

The overhead squat is definitely one of the least familiar lifts to many modern-day gym rats. The first time someone mentioned them to me, I had no idea what they were. As it turns out, the overhead squat is an excellent tool for building supporting strength and flexibility, as well as working the legs. Like the jerk variations, the overhead squat is primarily practiced by Olympic lifters. The basic premise of the lift is fairly simple.

The overhead squat is definitely one of the least familiar lifts to many modern-day gym rats. The first time someone mentioned them to me, I had no idea what they were. As it turns out, the overhead squat is an excellent tool for building supporting strength and flexibility, as well as working the legs. Like the jerk variations, the overhead squat is primarily practiced by Olympic lifters. The basic premise of the lift is fairly simple.

The weight is held in the lockout position overhead, with a very wide (snatch width) grip. I do believe that it's also acceptable to work the lift using a narrower grip at times, but generally, this lift is used as an assistance movement for the snatch, so the wider grip is much more common. Once you have secured the bar in a locked out position overhead, slowly descend into the full squat position. When I say "full squat," I'm talking ass-to-the-grass.

Many will find that they lack the flexibility in the ankles and hips to get into this extremely low position, although some stretching and practice will certainly help make this depth attainable. One key to remember is that the bar must remain directly overhead; do not be allow it to move to the front or rear when performing the lift. If the bar gets out of line with the center of gravity, you will lose the lift.

Initially, it's very difficult to maintain the proper bar position while descending into the squat due to the natural tendency to bend forward a bit when squatting conventionally. The key to maintaining your position is descending straight down into the squat while maintaining a very, very flat position. At the bottom of the lift, your head should be positioned a bit forward of the bar, but you should make a conscious effort to stay as upright as possible. After reaching the bottom position, begin the ascent in a controlled manner.

Once the lift is mastered, some explosiveness can be added to the rep cadence, but until such time, it's a good idea to maintain a very smooth, rhythmical tempo. Unlike a back squat, the ascent during an overhead squat requires the hips, back, head and bar to move in unison. During a back squat, sometimes our hips rise from "the hole" faster than our head (or the bar) but we can compensate for this prior to lockout. If the hips outpace the bar when rising from the bottom of the overhead squat, the lifter will naturally bend forward.

This shifts the center of gravity forward and increases the likelihood that the lifter will lose the bar. The idea that might help the straight up/down movement is to envision a piston moving up/down in a cylinder. There is no lateral or horizontal movement; only vertical movement. Obviously, this is an exaggeration of the true movement, but the imagery helped me maintain my straight back position and overhead bar position. After reaching the top position, it's time to go after another rep!

I was very pleased with the overhead squat's ability to help build the stabilizers in my shoulders and upper back, but I was also pleased with its direct effect of my quadriceps. Due to the extremely strict nature of the lift, I believe is isolates the quads nearly as well as the front squat.

Swings *

* (with dumbbells or kettlebells)

If you really want to go "old school" I'd like to suggest a lift that has a history going back to the turn of the century. The swing, performed with either a dumbbell or kettlebell, will help build explosive pulling strength in the back, traps, hips and legs. This lift was very popular with the strongmen like Arthur Saxon, Hermann Goerner, Thomas Inch and many others.

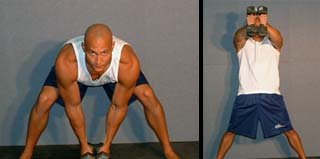

The equipment required is as basic as it gets. You only need one dumbbell or one kettlebell. Begin the lift by standing with a shoulder-width stance and the weight resting between the feet. Bend a bit at the knees and hips, allowing you to reach down and grab the handle. Squeeze the weight from the floor, and then slowly rock it back (toward the rear) to get started. This initial movement will help build momentum that's needed for the big pull. Next, pull hard in a forward and up direction, using the hips and legs to get the initial acceleration.

The equipment required is as basic as it gets. You only need one dumbbell or one kettlebell. Begin the lift by standing with a shoulder-width stance and the weight resting between the feet. Bend a bit at the knees and hips, allowing you to reach down and grab the handle. Squeeze the weight from the floor, and then slowly rock it back (toward the rear) to get started. This initial movement will help build momentum that's needed for the big pull. Next, pull hard in a forward and up direction, using the hips and legs to get the initial acceleration.

One key point is to never let the arm bend while performing the swing. The bell path will be more semi-circular rather than a purely vertical pull as performed in the clean or snatch. As the bell reaches a height close to the chin, quickly dip down into a quarter or half-squat position and catch the bar in a lockout position with the weight finishing overhead. Next, simply stand erect while holding the weight above you.

This movement bears some similarity to a one-handed snatch**, although the weight (as previously noted) doesn't follow a purely vertical path. The power is supplied primarily by the hips, legs and lower back, although the traps and upper back will come into play as the bar height passes the waist. Overall, the lift requires some degree of timing, flexibility and coordination, but is more forgiving on form than the snatch variations. As with other lifts that work the back, a flat back position should be maintained throughout the lift.

The intention of this article was to introduce some uncommon lifts that will yield excellent results when made a part of your strength training program. Aside from their benefits for those wishing to build muscle and strength, the athletic implications of each of these lifts should be apparent. Explosiveness is an asset in numerous sports, and these lifts can be added to the arsenal of anyone wishing to develop speed and strength. On the other hand, if you're more interested in power and strength, adding these lifts will likewise add a new dimension to your training.

The jerk and push press variations are perfect additions to any routine emphasizing shoulder development and strength. The overhead squat is a great way to either finish a heavy leg day or provide an additional leg workout during the week. Swings can be used to start a heavy back workout to loosen the muscles, or to build speed and coordination in preparation for the deadlift, clean or snatch. I sincerely hope that the readers of this article take can find new and interesting ways to experiment with these rare lifts and put them to use. Please feel free to contact me with any questions or requests for further information.

Thanks,

This article appears courtesy of www.mindandmuscle.net