Following that last set, a fellow gym rat I'd chatted with a few times in the past remarked, "Wow, it's amazing you're still hitting weights like that at your age!"

The implication, of course, was that I must have been significantly stronger in the past. It's an understandable assumption. After all, most serious lifters peak in their second or third decade, and then gradually decline after that (assuming that they continue to lift, of course).

"Actually" I replied, "that's a lifetime personal record for me!" I think my response resulted in more amazement than pulling four wheels for 10.

Being in lifetime-best shape at age 56 is unusual, but to be honest, my entire fitness journey is counter to the norm. I'd guess most people assume that highly visible fitness experts like myself were always fit, have great genes, are former professional athletes, are using steroids, or are just super disciplined. Those assumptions are often accurate, and in my own case, none of them are even remotely true.

To call my current level of success "unlikely" would be a significant understatement. On the other hand, that means there just might be more you can learn from it.

A Not-So-Inspiring Start

True story: when I was 15, after 4-5 years of dedicated karate training (I always thought that my destiny was to be a martial arts instructor), a friend's sister, unceremoniously and without remorse, pinned me in a backyard wrestling match. Now, in my defense, amy was a top-level volleyball player in school, she weighed almost as much as I did, and it's not like I was going to maim her with a disabling eye gouge. But none of that made it feel any better to me at the time.

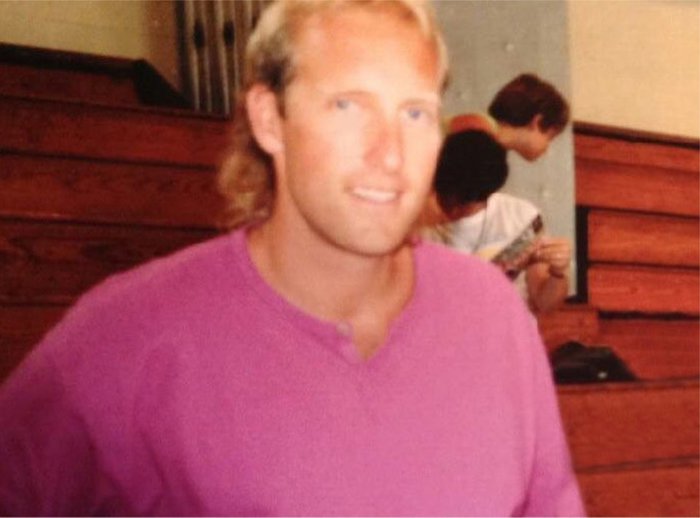

Unlike many athletes, i reached my physical peak at the age of 55.

Fast-forward to when I was 19, an age where most guys near their physical peak, and I can remember getting stapled by a 95-pound bench press. And just so we're clear, I'm not saying I missed the 20th rep; I was unable to bench 95 for a single friggin' rep. Right around that time, I can also remember being stunned that my buddy rich lloyd could bench 135 for 10. I couldn't fathom how someone could be that strong.

But wait, there's more! At age 21, I carried barely 140 pounds on a 6-foot-1 frame, and I had a gut even then, despite 3-4 grueling martial arts classes, 2-3 weight-training workouts, and 1-2 jogging sessions per week. If anyone out there ever did more work for less gain, I'd like to meet him.

Fast-forward another 10 years, and I was long past the point where anyone was calling me skinny. I had been lifting for over 10 years, but you'd never know it. Funny thing was, I honestly didn't realize I was fat, if you can believe it. I have an unusual strain of delusional optimism when it comes to self-assessment.

And Yet, I Was A Trainer—And A Good One!

In my early 30s, my career took a sudden turn. I had been running a YMCA weight room and doing personal training on the side (though it wasn't called "personal training" yet). At a weightlifting competition in Queens, New York, I met Dr. Fred Hatfield, who at the time was just launching his latest brainchild, the International Sports Sciences Association (ISSA), now a respected personal training certification agency. I'm not sure exactly what I said to him or how I managed to convince him I had any value at all, but six months later, I was sitting in Santa Barbara helping Fred's partner, Dr. Sal Arria, with ISSA.

Moving to California also opened my eyes to a new level of training. Prior to moving, the biggest lift I had ever witnessed was a 500-pound squat. Three weeks after landing in Santa Barbara, I saw a guy bench 600 for a double. Within a few weeks after that, my strength levels increased 25 percent by pure osmosis—we truly are the average of the five people we hang around with most.

While in California, I met and befriended all sorts of fitness luminaries, including Tom Platz, Paul Ward, Dr. James Wright, Jane Frederick, Eddie Coan, and a host of top-tier bodybuilders and fitness celebs. I penned my first article in Muscle & Fitness, taught weekend fitness certifications for the ISSA, and before you knew it, I had a made a name for myself in the fitness biz.

But, despite all this, I didn't look the part—not even close. How anyone ever hired me or took me seriously is beyond me. My best guess was that I talked a good game, and, yeah, I was competent at my job.

I just never managed to apply what I knew to myself.

A Quiet Conviction Takes Over

As you get older and your circumstances change with the seasons, avoid emotional or otherwise irrational attachments to any particular approach or strategy.

It continued more or less in this vein until one morning in 2013, when I looked in the mirror and thought, "I'm gonna get lean once and for all, no matter what."

I'm not sure what sparked that sudden conviction, and it didn't seem terribly dramatic at the time. But suddenly, I was possessed by a quiet resolve. I knew that my abysmal nutrition habits were my Achilles's heel. I'll keep the details to myself, but picture the worst nutrition you can imagine, and then make it about 20 percent worse, to get you in the ballpark. So I began to shop around for a nutrition coach, which eventually led me to Eric Helms. I couldn't have made a better choice, at least for me.

Over the course of about 40 weeks, using a flexible dieting approach, I dropped about 23 pounds of excess baggage, while at the same time maintaining my strength—and by implication, most of my lean body mass.

My reaction to "suddenly" looking like the fitness expert that I claimed to be? "Why the hell didn't I do this sooner?"

I still can't answer that question. But three years after I finally got (reasonably) lean, I'm regularly setting new lifetime PRs in the gym, and I'm confident that I'm nowhere near being finished.

One of the big takeaways from my story is that successful people don't necessarily do everything right. Instead, we are all the sum of our beneficial decisions and habits, minus our unproductive behaviors. If I had it all to do over again, here's how I would have approached this project from the start.

1. Surround Yourself With Supportive People

Picture a standard bell curve, portraying success in the population. A minority of people are super successful, another minority are super unsuccessful, and vast the majority, well, they're just doing "OK."

Very reliably, whenever you start to seek excellence in any arena, your friends, family, and acquaintances will often—usually unconsciously—attempt to sabotage your efforts. Why? Maybe, as many people say, your success makes their lack of success all the more evident. Maybe they just don't "get" the idea of being so serious about something, and want to help you pull back to the OK norm.

Whatever the reason, it's crucial that you counteract it by finding people who will actively support your efforts. This could be a coach, a training partner, or an online community of folks who understand and support your efforts (BodySpace is a good place to start.) Better yet, all three.

2. Be Willing To Revise Your Beliefs

Five years ago, I considered machines a total waste of time. I often mocked the notion of walking as exercise, and I regularly recommended very-low-carb diets. Today, I've reversed my position on all three of these topics. I'm not afraid to admit it!

It's critical to stay open to opposing points of view. In fact, for any opinion you hold, you should be capable of debating the opposing point of view. Especially as you get older and your circumstances change with the seasons, avoid emotional or otherwise irrational attachments to any particular approach or strategy.

3. Value Progress Over Perfection

On the front end of changing your life, it's easy to think that as soon as your training and diet are "perfect," you'll be happy. The problem, of course, is that they will never be perfect, and the time and effort you spend trying to reach this impossible standard can make you miserable.

Can't do your entire workout because an unexpected problem popped up? Do the most important 1-2 exercises anyway. A half-assed session is much more productive than a missed one.

Dealing with a bum shoulder? That sucks. Do what you have to do to make it right, then use this as an opportunity to do something about your puny calves.

4. Don't Forget About Muscle

Training for strength is addictive, to say the least. For much of my life, my training involved working up to a heavy single, or triple, or a set of 5. If I could set a new PR, I knew I was making progress, and I had something that would keep my spirits up all week.

In other words, I was looking for immediate gratification.

Because of this pattern, however, I never put in the volume necessary to build the level of muscle that, in hindsight, I should have. Sure, I might do a big set of 8 or 10 to break a rep record, but it wasn't until very recently that I'd bang out 4-5 hard sets of 10.

This is perhaps my primary training regret at age 56, and at this stage, it's probably too late to make a huge difference. If you're a younger guy reading this, take heed. And if strength is important to you, consider alternating strength and muscle-building blocks like I discuss in my article "5 Rules to Build Strength and Size."

5. Take The Long View On Nutrition

The rewards of eating well are not realized for months or even years. There's no immediate gratification to be derived from eating perfectly for a day or a week. This made it hard for me to get serious about nutrition.

In other words, I needed to grow up.

The ability to delay gratification is a key measure of maturity. So is the ability to keep rolling past a bump in the road. So you gave in to temptation and ate a pint of Häagen Dazs? Look, you'd have to eat three of those in a week on top of your normal calories to gain a pound of fat. It's hardly a disaster. Just wipe the slate clean and get back on the plan.

6. Trick Yourself Into Mobility

My 20 years of martial arts training left me with a disdain for anything that even smelled like stretching. However, in retrospect, the mobility I gained during those years probably has plenty to do with my current level of orthopedic health, despite many years of very heavy lifting.

This realization has led me to look for ways to reintroduce mobility work into my overall training plan as I enter my mid 50s. My current strategy, believe it or not, it to "trick" myself into doing it. The other day, I kicked the heavy bag for a bit (to be clear, I've been away for martial arts for most of the last 30 years), and to my surprise, I can still kick almost as well as I ever could—except for high kicks that is.

If I could regain my previous levels of hip mobility, I'd pretty much have my kicking skills back, which is an intriguing notion for me. That's what I mean by "tricking" myself; my desire to improve my kicking skills will motivate me to get more flexible. Think of what could "trick" you, because it will be the thing that saves you from hours of boring "prehab" work.

Even At Age 56, I'm Still Excited To Improve!

I used to have a friend who called the gym his laboratory because it was where he learned lessons he could apply to other areas of his life. I can definitely relate—more so every year. The lessons I'm imparting in this article are by no means confined to the gym or the kitchen.

Sure, as I age, progress is slower—who am I kidding , it's much slower!—but that's an opportunity to further refine my problem-solving skills. Approach fitness with the right mindset, and you'll not only look better and live longer, but also live better. That's what this is really about.