We've all experienced it, the intense muscle pain from delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) that comes a day or two after an intense workout. But you may have noticed that as your training became more and more consistent, those days of not being able to comb your hair or walk up a flight a stairs without difficulty due to severe DOMS have gotten few and far between. These days you really have to train with balls-to-the-wall intensity to get just the slightest DOMS in your pecs or biceps.

Some of you may be worried about this lack of muscle soreness from your training. Maybe you're not doing it right. After all, if you've read anything about muscle growth you know that muscles grow by being damaged and then rebuilt bigger and stronger than they originally were. Right? Although muscle damage definitely leads to muscle growth and strength gains, there is some debate over whether it's absolutely critical for long-term muscle growth.

Get out your microscopes. In this article, I'll take you deep into the muscle cells to look at how a muscle grows and investigate whether muscle damage is completely critical for muscle growth.

Muscle Damage Discoveries

A lot of research has been done on muscle damage and its effects on muscle hypertrophy. In fact, we know a great deal about the processes involved in muscle damage and how they influence muscle growth. Muscle damage can happen from mechanical or chemical stress. Muscle damage from mechanical stress usually occurs when lifting heavy weight.

In simple terms, muscle fibers contract by a ratchet mechanism. A specific protein called myosin connects to another protein actin and then pulls the actin closer. Thousands and thousands of actin and myosin connections are occurring in each muscle fiber when you lift a weight. This action shortens the muscle and is basically how a muscle contracts to lift a weight.

Consider the shortening of your biceps muscles as your arms flex at the elbows to curl a barbell. Then when you lower the weight back down, the muscle must lengthen. To do this, the myosin allows the actin to slide back to its original position and then it disconnects. However, when the weight is extremely heavy, the muscle fiber often cannot resist the weight back down and the force of the weight literally tears the myosin right off of the actin. This shearing force also damages other critical structures of the muscle fiber.

Even when you're not using heavy weight, similar muscle damage can occur. When the muscles become fatigued from performing too many reps, again they have difficulty resisting the weight when the muscle fiber is lengthening. And again, the actin and myosin are forcibly ripped apart, causing damage. This type of damage is similar to a wound that you get anywhere on your body.

Immediately following the damage, an inflammatory response ensues that eventually leads to healing of the muscle fiber even bigger and stronger than it previously was. This inflammatory response is a long cascade of events involving many different white blood cells, cellular signaling messengers, chemicals, fluid, growth factors, and special cells known as satellite cells.

Once damage happens, the first cells to arrive on the scene are neutrophils. These specialized white blood cells secrete chemicals, such as enzymes and toxic chemicals, which further break down the damaged tissue. Following on the heels of the neutrophils are another type of white blood cell, macrophages. After the tissues are adequately decomposed, the neutrophils and macrophages literally consume and remove them from the site in an effort to clear it out and prepare for the makeover.

While all this breaking down and gobbling up is going on within the muscle cell, large amounts of fluid are filling it up, as well as the surrounding area, causing swelling.

From Damage To Growth

The macrophages that helped to clean up and remove the damaged tissue also secrete chemicals that play a small yet critical role in numerous processes and eventually lead to the activation and growth of satellite cells. Satellite cells are specialized muscle stem cells that sit dormant in a muscle but then migrate to the area of damage, bringing their nuclei into the muscle cell. The satellite cells fuse into the existing muscle fiber, typically becoming one cell, but now with more nuclei.

Since the nuclei of muscle cells are the headquarters where muscle building originates, the more nuclei that a muscle cell contains, the more proficiently it can grow. And over time the muscle grows bigger and stronger.

Satellite cells are the critical factor in how big a muscle can get. Studies confirm that weight-trained subjects with greater muscle mass have more nuclei per muscle fiber and cell. The higher nuclei content has also been shown to control the phenomenon known as "muscle memory," where a previously trained person can rebuild muscle that they lost faster than someone who never had the muscle mass to begin with.

That's because the extra nuclei build up more muscle protein quicker than a cell with fewer nuclei. The cell swelling that comes with the inflammation from damaged muscle can also help encourage muscle growth. When a muscle cell fills with fluid, it places a stretch on the muscle cell membrane. This stretch signals the cell to increase the size and strength of its structure to prevent the swelling from literally popping the cell.

To do so, the muscle cell increases muscle protein synthesis and simultaneously decreases muscle protein breakdown. This is one reason why supplements such as creatine, taurine, and glutamine (which can pull more fluid into the muscle cells) can help to increase long-term muscle growth.

Is Damage Really Necessary?

Clearly muscle damage is a good thing when it comes to bodybuilding. After all, the only way to maximize muscle size is to increase the number of nuclei in the muscle cells to as many as possible. Yet causing muscle damage is a difficult thing the more training experience you have.

Bodybuilders with at least a few years of consistent training under their belts can tell you that they rarely get sore unless they really take on severely intense training with unique intensity techniques that they haven't done in a while. That's because the muscle builds up a protective mechanism against muscle damage. Exercise scientists refer to this as the "repeated bout effect." Although scientists are unsure of precisely why this happens, the fact is that once you damage a muscle fiber, it is next to impossible to damage it again, at least for several months.

Luckily, muscle cells have more than one trick up their sleeves to grow. In addition to adding new nuclei to damaged muscle fibers, muscle also grows by increasing the amount of protein it contains. A muscle is composed primarily of protein—at least the structural components of it are. So another way that muscle grows is by synthesizing more muscle protein, through a process termed "muscle protein synthesis."

Muscle protein synthesis is the build up of muscle protein one amino acid at a time. This takes place in and around the nuclei of the muscle cell. In the nuclei, the DNA houses the genes that encode the sequence of each specific protein a muscle contains. When the nuclei receive a signal to activate certain genes to build more protein, they replicate the sequence of the proteins with messenger RNA (mRNA). The mRNA then leaves the nuclei and single amino acids are brought together to form a long chain that makes up the protein that builds up the muscle.

Of course, this is a very simplified recount of what actually takes place. One major way that the nuclei receive the signal to activate genes and synthesize more muscle protein is from working out. Both the mechanical stress from the weight being lifted, and the chemical stress produced inside the muscle from generating energy to contract, activate genes to increase muscle protein synthesis.

Numerous chemicals and biochemical pathways are involved in creating these signals, but some of the major players include: mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase), testosterone, growth hormone, IGF-1, cytokines, and insulin.

As long as adequate amino acids are supplied to the muscles during and after the workout (hence, be sure to get in your pre- and post-workout shakes), muscle protein synthesis following workouts will produce significant increases in muscle growth. Yet, muscle protein synthesis from one nucleus can produce only so much muscle growth.

So the best strategy is not only to train to maximize muscle protein synthesis, but to also increase numbers of muscle cell nuclei. With more muscle cell nuclei, you get greater muscle protein synthesis in each muscle cell and that leads to the greatest muscle growth. So how do you maximize both muscle protein synthesis and muscle cell nuclei content when muscle damage becomes more and more difficult to achieve with the more training experience you gain? See my strategies below.

Keep Growing

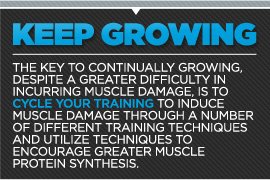

The key to continually growing, despite a greater difficulty in incurring muscle damage, is to cycle your training to induce muscle damage through a number.

Perform one workout for each muscle group that involves negative-rep training. To do this choose weight that is about 20% greater than the amount you can lift normally for one rep. Have a spotter assist you on the positive. Do three or four exercises per muscle group. Do one or two sets of three to five negative reps (resist the negative rep for about three to five seconds) for each exercise.

Follow the negative rep sets of each exercise with two sets of three to six regular reps. Do this workout just once every two to three months.

The week following your negative-rep training, keep weights light and reps high at about 15-20 per set. The higher rep range will cause more metabolic stress in the muscle fibers, encouraging greater muscle protein synthesis.

For two or three weeks, train each muscle group a minimum of twice per week and preferably three times per week. Your best bet is to use a two-day split that trains all the muscle groups over two workouts. Repeat the workouts three times each week.

Of course, total sets per muscle group will have to drop to allow time to train so many each workout. But remember that you will be hitting that muscle group again in two days. By the end of the week you'd still have completed more total sets for that muscle group than you would've with one workout per week.

For the next two to three weeks keep reps in the sweet spot for muscle growth, 8-12 reps per set, and do three to four forced reps at the end of every working set. If you train alone, you can do forced reps on single-limb exercises such as dumbbell concentration curls by assisting with the non-working arm.

For bilateral exercises such as the bench press, use dropsets instead. Going past muscle failure will produce metabolic waste products that can lead to chemical-induced muscle damage and help to bring more nuclei into the muscle cells.

Going past failure will also place mechanical stress and metabolic stress on the muscle fibers to increase growth through muscle protein synthesis.

Now that you've incurred some muscle damage through chemical means and hopefully increased your muscle nuclei content again, it's time to allow your muscles to recover and focus on boosting muscle protein synthesis. For the next one or two weeks, keep your rep range at 25-30 per set.

Several recent studies have shown that using a very light weight for very high reps increases muscle protein synthesis better than using very heavy weight for low reps.

For the next four weeks, follow a workout schedule where you train each muscle group once per week and each week the weight gets heavier and reps get fewer. You were previously training in the 25-30 rep range, so continue in that fashion and consider using these rep ranges for each of the four weeks: Week 1 = 15-20 reps, Week 2 = 10-12 reps, Week 3 = 6-8 reps, and Week 4 = 3-5 reps.

Weeks 1 and 2, and even Week 3, will help to increase muscle protein synthesis. Weeks 3 and 4 work to maximize muscle strength, which is also important for encouraging muscle growth. The stronger you are the more overload you can place on a muscle. And that overload can help to increase muscle growth and it can increase muscle damage, leading to further muscle growth.

This strength will be important when it's time to cause some mechanical damage again, as the more weight you can handle the more muscle damage you can incur.

Set a four-week training program that starts with rest at two minutes per set. Each week reduce rest periods by 30 seconds so that in week 4 you are resting just 30 seconds per week. A recent study found that subjects reducing their rest time between sets over an eight-week training period increased muscle mass better than those keeping their rest periods steady at 2 minutes.

The constant dropping of rest between sets produces metabolic stress on the muscles, which encourages an increase in muscle protein synthesis. One of the key players in this strategy is locally produced IGF-1 in the muscle fibers.

By now, at least three months should have elapsed since you last trained with negative reps. The protection of the repeated bout effect should have elapsed, and you can finally enjoy some negative-rep-induced muscle damage, along with the DOMS and satisfaction of knowing that you're increasing muscle nuclei content, and that is going to help you maximize your muscle growth.