Are Superfoods Really ''Super''?

Each day, a new food seems to get promoted to superfood. But can the latest and greatest fruits and veggies really help you lose weight and prevent diseases? Find out here!

When does a food become a full-fledged superfood? The question is easy to ask, given how the "super" prefix has invaded the health media in recent years. But the answer might surprise you.

Based on popular usage, ordinary food graduates to "super" status when it is considered to be beneficial to your health, or when it contains multiple healthy nutrients in high doses. It is most commonly used these days to refer to foods that are rich in nutrients connected to ongoing research into disease treatment and prevention. A few examples include acai berries, goji berries, other dark berries, pomegranate seeds, sweet potatoes, spinach, kale, adzuki beans, and quinoa.1

These foods have a lot going for them, but not necessarily what their biggest fans will have you believe. Let's take a look at the most common claims you'll encounter online.

Who Decides What's Super?

You can find references to the word "superfood" seemingly everywhere online—and yes, it's even in the dictionary.2 But guess what? That doesn't mean anything. The term "superfood" is not a regulated food claim (nor is "natural," at least in the United States), which means that it can be applied to any food without consequence.

In other words, there's nothing stopping me from saying that Mountain Dew is a superfood. After all, it's green, right?

In general, though, the label is reserved for foods that are high in vitamins, minerals, essential fatty acids, and antioxidants. When compared to Mountain Dew—which isn't rich in anything but sugar, caffeine, and colorants—a so-called superfood like kale is definitely a better choice.

But while superfoods are generally healthy, the magical superpowers they are often portrayed as having usually don't stand up to scrutiny.

Claim 1 Superfoods Will Help You Lose Weight

One of the most widely purported benefits of superfoods is that eating them will result in weight loss. However, there is no evidence that any individual food can significantly affect your metabolic rate or assists with weight loss.

Like any food, superfoods provide the body with energy in the form of calories. But eating these foods won't magically speed up your metabolism. And as with any other food, you can actually gain weight from these foods if you eat too much. This is especially true if you favor superfoods in the form of sugar-rich juices.

It's worth noting that many superfoods are high in fiber, which can increase feelings of fullness, and that can certainly help you eat fewer calories.3 Most are also low-glycemic-index foods, which means they produce minimal insulin response when you eat them and won't put you on the blood-sugar rollercoaster that can cause poor food decisions. Those are both desirable traits, but they're also true of pretty much any food high in fiber and definitely aren't unique to superfoods.

Take-Home Advice

Superfoods have not been shown to result in weight loss alone. To lose weight, exercise consistently and eat in caloric deficit throughout the day.

Claim 2 Superfoods Can Clear Out Toxins From Your Body

Some advocates of superfoods recommend consuming large quantities of nutrient-dense foods to detoxify the body, based on the belief that diet-induced toxins can cause an increase in body-fat levels.

Fortunately, the human body is fully capable of removing such toxins and doesn't require the help of any specific foods to do so. The kidneys and liver eliminate potentially dangerous compounds so they do not build up to toxic concentrations and cause health problem.4 As of yet, there is no evidence that any food or product is capable of removing toxins from the body.

Take-Home Advice

The body is well-equipped to remove metabolic byproducts and potential toxins via the kidneys and liver. If yours isn't, you need to see a doctor, not just eat a certain food.

Superfoods, detoxifiers, and cleanses have not demonstrated the ability to remove toxins on their own and therefore should not be used for that purpose.

Claim 3 Superfoods Will Help Balance Your Body's pH Level

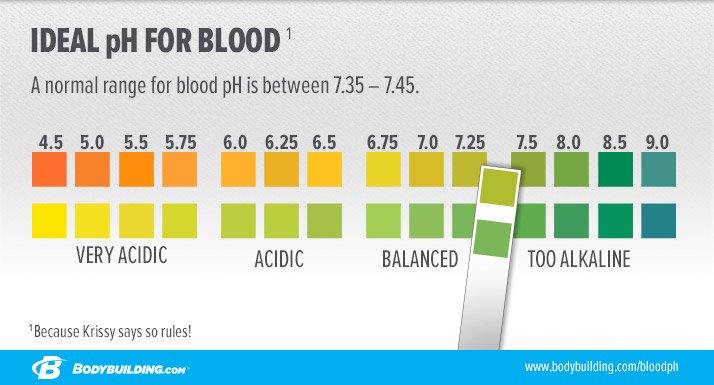

Due to their basic pH, it is often proposed that fruits and vegetables can help to balance the body's pH level.5 A normal range for blood pH is between 7.35 and 7.45.

However, the body is equipped to tightly regulate blood pH on its own via the kidneys. When blood becomes acidic, the kidneys excretes hydrogen ions in urine (acidic) and produce bicarbonate ions (basic) that enter the blood and neutralize the pH to keep it in this narrow range.6 If the body is unable to maintain a normal blood pH range, serious health consequences such as cardiovascular complications, vomiting, muscle weakness, mental confusion, and bone pain can result.7

Although your foods choices don't have a major impact on blood pH, they can impact urine pH. For example, a diet high in fruits and vegetables may increase urine pH, while a diet high in meat, dairy, and grains may reduce urine pH. However, the fluctuation in the pH range of urine is not as detrimental compared to a slight fluctuation in blood pH.

Take-Home Advice

Specific foods haven't been shown to pose a risk of altering the body's blood pH. If you display symptoms of a low blood-pH value, this is a medical concern, not a dietary one.

Claim 4 Superfoods Can Prevent or Cure Diseases

This is the big one. Most if not all superfoods are promoted as having disease-preventing or disease-curing properties. The companies and individuals making these claims usually present scientific studies that, upon first glance, appear to support the notion that individual foods can impact a disease. But let's look closer.

Studies that suggest food can play a role in preventing specific diseases are typically performed using a cell culture in a lab. In these studies, cells are grown in a dish and treated with extremely high amounts of an individual nutrient extracted from a food, often resulting in a beneficial effect.8-10

Simple enough, right? Hardly! While a large dosage of the nutrient may have a beneficial effect on cells in the dish, you are (hopefully) not cells in a dish. Saying that a food—one of many that you eat—will navigate your digestive system and mange to produce the same effect as isolated nutrients in a cell culture is speculative, to say the least.

But what about animal studies? Resveratrol (found in red wine), luteolin (a flavonoid found in many herbs and peppers) and sulforaphane (found in cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli) have all been shown to have positive health benefits in animal models.11-13 Unfortunately, most of these studies used mega dosages of the nutrients of interest. It would be impractical to consume such a high dosage of said nutrients, and even if you did, it's again highly speculative to assert it could achieve a specific effect in any given human body.

And as for human studies? Most studies looking into individual foods and disease are cohort studies, where scientists follow a group of people for a number of years and attempted to draw conclusions based on their observations.14,15 Using this type of research, scientists have correlated certain foods eaten with specific outcomes. For example, researchers followed over 86,000 women during a 10-year period and found that those who consumed nuts on a regular basis had a lower risk of cardiovascular disease.16

But before you sell your house and move to an almond farm, you should know that cohort studies have several significant limitations. First and foremost, they usually rely on self-reported dietary recalls from subjects. This method has several well-known flaws, including poor individual recall and false representation of an individual's habitual food intake.17,18

Second, cohort studies do not prove anything. Rather, they can only show there is an association between a specific food and risk of a disease. To date, there is simply no conclusive evidence that consumption of any individual food has a significant effect on disease.

Take-Home Advice

There is no evidence that an individual food can prevent or cure disease in humans. To reduce disease risk, eat a diet consisting of a variety of food from all food groups, be physically active, and maintain a healthy body weight.

Food Trumps Superfood

Am I telling you not to eat superfoods? Definitely not! Nutrient-dense foods are a welcome addition to any plate and can definitely help ensure that your nutritional needs are being met. But none of them—not a single one—is a silver bullet capable of transforming the overall state of your nutrition. If junk is your norm, even the most super of superfoods won't cancel that out.

While superfoods are high in essential vitamins and minerals, essential fatty acids, antioxidants, and phytonutrients, there is nothing inherently "super" about them. But if you make them part of a healthy overall approach to nutrition, fitness, and life, well, that's super.

References

- Lunn, J. (2006). Superfoods. Nutrition Bulletin, 31(3), 171-172.

- "superfood." In Merriam-Webster.com Retrieved October 26, 2015, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/superfood

- Anderson, J. W., Smith, B. M., & Gustafson, N. J. (1994). Health benefits and practical aspects of high-fiber diets. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 59(5), 1242S-1247S.

- Widmaier, E. P., Raff, H., & Strang, K. T. (2013). Vander's human physiology: the mechanisms of human body function. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Remer, T., & Manz, F. (1995). Potential renal acid load of foods and its influence on urine pH. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 95(7), 791-797.

- Koeppen, B. M. (2009). The kidney and acid-base regulation. Advances in physiology education, 33(4), 275-281.

- Seifter, J. L. (2004). Acid-base disorders. Cecil Textbook of Medicine, 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 688-699.

- Ford, N. A., Elsen, A. C., Zuniga, K., Lindshield, B. L., & Erdman, J. W. (2011). Lycopene and apo-12?-lycopenal reduce cell proliferation and alter cell cycle progression in human prostate cancer cells. Nutrition and cancer, 63(2), 256-263.

- Narayanan, B. A., Geoffroy, O., Willingham, M. C., Re, G. G., & Nixon, D. W. (1999). p53/p21 (WAF1/CIP1) expression and its possible role in G1 arrest and apoptosis in ellagic acid treated cancer cells. Cancer letters, 136(2), 215-221.

- Yi, W., Fischer, J., Krewer, G., & Akoh, C. C. (2005). Phenolic compounds from blueberries can inhibit colon cancer cell proliferation and induce apoptosis. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 53(18), 7320-7329.

- Thandapilly, S. J., Wojciechowski, P., Behbahani, J., Louis, X. L., Yu, L., Juric, D., ... & Netticadan, T. (2010). Resveratrol prevents the development of pathological cardiac hypertrophy and contractile dysfunction in the SHR without lowering blood pressure. American journal of hypertension, 23(2), 192-196.

- Johnson, J. L., & de Mejia, E. G. (2013). Interactions between dietary flavonoids apigenin or luteolin and chemotherapeutic drugs to potentiate anti-proliferative effect on human pancreatic cancer cells, in vitro. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 60, 83-91.

- Liu, A. G., Juvik, J. A., Jeffery, E. H., Berman-Booty, L. D., Clinton, S. K., & Erdman Jr, J. W. (2014). Enhancement of Broccoli Indole Glucosinolates by Methyl Jasmonate Treatment and Effects on Prostate Carcinogenesis. Journal of medicinal food, 17(11), 1177-1182.

- Streppel, M. T., Ocké, M. C., Boshuizen, H. C., Kok, F. J., & Kromhout, D. (2009). Long-term wine consumption is related to cardiovascular mortality and life expectancy independently of moderate alcohol intake: the Zutphen Study. Journal of epidemiology and community health, 63(7), 534-540.

- Kurahashi, N., Sasazuki, S., Iwasaki, M., & Inoue, M. (2008). Green tea consumption and prostate cancer risk in Japanese men: a prospective study. American journal of epidemiology, 167(1), 71-77.

- Hu, F. B., Stampfer, M. J., Manson, J. E., Rimm, E. B., Colditz, G. A., Rosner, B. A., ... & Willett, W. C. (1998). Frequent nut consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women: prospective cohort study. Bmj, 317(7169), 1341-1345.

- Lichtman, S. W., Pisarska, K., Berman, E. R., Pestone, M., Dowling, H., Offenbacher, E., ... & Heymsfield, S. B. (1992). Discrepancy between self-reported and actual caloric intake and exercise in obese subjects. New England Journal of Medicine, 327(27), 1893-1898.

- Poslusna, K., Ruprich, J., de Vries, J. H., Jakubikova, M., & van't Veer, P. (2009). Misreporting of energy and micronutrient intake estimated by food records and 24 hour recalls, control and adjustment methods in practice. British Journal of Nutrition, 101(S2), S73-S85.